View PDF - Notre Dame Law Review

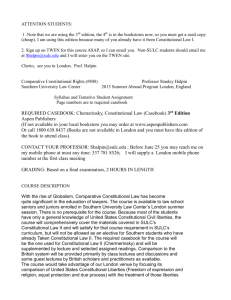

advertisement