The Tragedies

advertisement

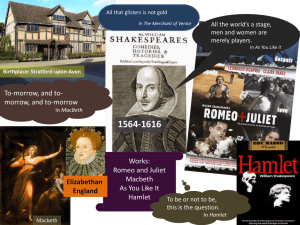

A Guide to the Plays The Tragedies To keep with our simple definition, if no one dies in a comedy, then obviously someone dies in a tragedy – and usually the title character, along with many others. The tragedies can provide a rich experience for exploring very real themes: action and its consequences, love and loss, family struggles. We recommend these plays mostly for more mature, self-directed students drawn to puzzling over serious questions. Though fourth and fifth grade groups sometimes perform heavily cut versions of Macbeth or Julius Caesar, there is often the risk of trivializing the violence and harsh reality Shakespeare portrays. On the other hand, considering what kids might see when the television is left on for very long, the internal drama of these stories – Macbeth’s agonizing struggle with his conscience, or Brutus’s grappling with the decision to assassinate Caesar, for example – can provide a powerful antidote to the callousness of much televised mayhem. As with the comedies, there are terrific moments in all of the tragedies that are worth studying with children. But we think these three tragedies provide the best opportunities for whole-play exploration by mature kids: Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and Macbeth. Hamlet Like Tempest, Hamlet throws us right into something spooky and mysterious – in this case, the ramparts of a haunted castle at night. The opening scenes with the ghost of Hamlet’s father are wonderful for the dramatic pacing, the evocation of a powerful mood, and the crispness of the language. From there, of course, you are propelled into the struggles of perhaps the most famous character in all of Western literature – young prince Hamlet, struggling to make sense of his life and the world around him. When you ask kids to quote one Shakespeare line, almost always the first one is, “To be or not to be.” So it’s great to be able to explore this famous line in context, and see what comes after it. Hamlet is a very long play, and needs substantial editing to work for children. Also, the role of Hamlet dominates much of the play, so the lines are not evenly distributed. One solutions is to “tag-team” the major roles and have 5 or 6 Hamlets, each taking a different part of the play. This also has the benefit of giving more kids the direct experience of playing this amazing character. As in most of the tragedies, the final scene requires great commitment and concentration. Anything less, and it can easily become as silly and comical as “Pyramus and Thisbe” in “Midsummer.” So be sure you have kids willing to take the death scenes seriously. Romeo and Juliet The second most often-quoted bit of Shakespeare by kids, in our experience, is “Romeo, Romeo...” This is a play that, partly thanks to hip film versions in the 1960s and 1990s, seems eternally fresh for young people. Almost everyone, amazingly, knows something of the story of Romeo and Juliet, 400 years after Shakespeare turned this clas- sic tale into a brilliant play. Sixth grade girls love the character of Juliet, and boys of all ages love the swordfighting, so it’s a dynamic package for a mature group of kids. The challenge is often finding a boy ready to take on Romeo. If you can, then you’re in for something special. One fifth grader we worked with one year at Blackshear Elementary in Austin became so enamored of being thought of as the famous young lover that he even adopted “Romeo” as his nickname for years afterwards. The Prologue and the opening scene – the brawl between the Capulets and Montagues – combine for another terrific jump-start for a Shakespeare project. There are also wonderful scenes to explore between Juliet and her family and Romeo and his buddies. This play, like Hamlet, will need substantial editing for a group of young players. Macbeth This is one of Shakespeare’s darkest and most nightmarish plays, but kids seem to be fascinated by it – perhaps for the same reason they’re drawn to Halloween costumes or scary stories. For opening scenes in Shakespeare, it’s hard to get more creepy than the three witches, or Weird Sisters, who with their chant of “Fair is foul and foul is fair” immediately signal to us that something bad is going on. Lady Macbeth is a fantastic character study, Macbeth has powerful speeches, and there is plenty of startling action, including a great swordfight at the end. The most attractive element of this play for us, from a teaching standpoint, is the harrowing look at what happens when you choose – against your better wisdom – to harm others. The actions of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth open up powerful possibilities for classroom discussions about good and evil, right and wrong, selfishness and generosity, and the impossibility of reversing some courses of action – “What’s done cannot be undone,” as Macbeth says, both numbed and horrified at the reality of that truth. In our experience, even third-graders can be fascinated by looking into the mind of a character as he wrestles with himself over whether to do something “bad” or not. There is also the question of what influence the “supernatural” elements have on the play’s characters. Do the witches lead Macbeth into murder, or do they merely bring out into the open what was already going on in his thoughts? The play is in many ways a fascinating psychological study. Again, it takes a mature group of kids to tackle these elements and not reduce the play to a cheesy horror show with kilts. And there are some truly terrible moments – including the one where Macduff’s family is massacred – that are not to be taken lightly. Sometimes an edited and streamlined version of the play is more appropriate for younger students. One good starting point is to focus on analyzing and exploring Macbeth’s famous soliloquies, especially the one in which he agonizes over whether to kill the king (“If it were done...”). This can bring out a depth of response in the students and show how Shakespeare uses language to capture internal struggles and states of mind (“How full of scorpions is my mind, dear wife!”). Other tragedies There are amazing and powerful scenes in all the other tragedies, King Lear especially. We have often considered working on Lear with young people. But the play is so agonizing at points that it would be very difficult to do without a very mature and sensitive group of students. It’s probably best to look at individual scenes from these plays (Othello is another) that can be pulled out and explored. The impact of these scenes will be strong, and perhaps will eventually lead the students to read these plays later, when they are older.

![Quote Integration Handout (Carmen)[2]Payne.doc](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008031414_1-35de2d3b7caafe44cd7f796bb2c99f35-300x300.png)