understanding the new confrontation clause Analysis

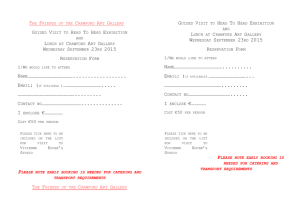

advertisement