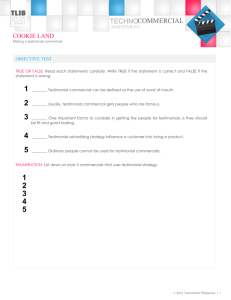

TOWARD A UNIFIED THEORY OF TESTIMONIAL EVIDENCE

advertisement