Legal but Unethical: Interrogation and Military

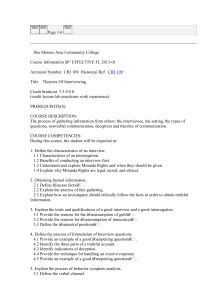

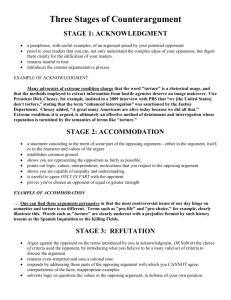

advertisement