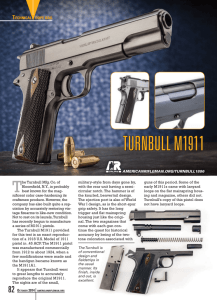

Implementing Turnbull

advertisement