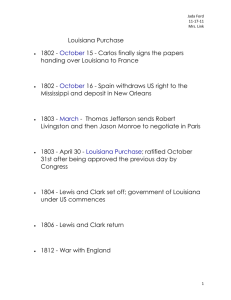

voting rights in louisiana: 1982–2006

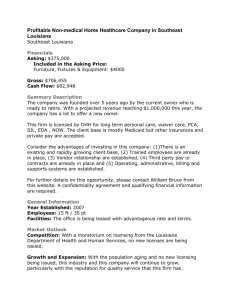

advertisement