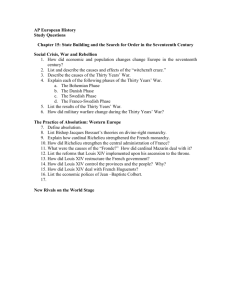

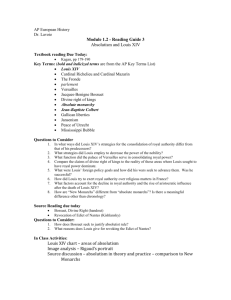

Absolutism and Constitutionalism

advertisement