Environmental Reporting Standards: The More Things

advertisement

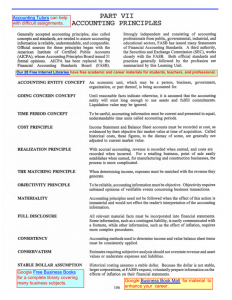

ORGANIZATIONAL RESISTANCE TO CHANGE: THE FASB AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACCOUNTING Janet Luft Mobus, PhD Assistant Professor of Accounting Business Administration Program University of Washington, Tacoma 1900 Commerce St. Tacoma, WA 98402 USA Phone - (253)692-5810 email - jmobus@u.washington.edu 2 ORGANIZATIONAL RESISTANCE TO CHANGE: THE FASB AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACCOUNTING ABSTRACT Organizational resistance to change using the context, process and content of environmental disclosure standard setting by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is examined. The process is one of discourse as developed by Habermas and applied by Biesecker, Kesting, and Renn. The content of environmental disclosure requirements mandated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are reviewed by way of contrast to the actions of FASB. The study is motivated by literature on organizational behavior that predicts organizational responses to demands for change (Pettigrew, 1987; Miller and Friesen, 1980a, 1980b; Laughlin, 1991), and relies on Laughlin’s (1991) model of change. Organizational behavior is further informed by the theory of discourse, which plays a role in internally devising the organizational response to demands for change. The response by US professional accounting standard-setting organizations to demands for expanded environmental performance disclosure is characterized as one of form over substance. 3 INTRODUCTION During the mid 1990’s, accounting standard-setters in the US debated the extent, nature, and form of environmentally related disclosures. Financial reporting largely addresses disclosure of remediation-cost exposure resulting from status as a potentially responsible party (PRP) on Superfund sites. However, estimates of compliance costs under other statutes (e.g., Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act) are also substantial. Therefore, establishing reporting standards for current operations affected by these other statutes is also appropriate. Also ignored thus far by accounting standards is reporting of remediation efforts undertaken voluntarily by firms (i.e., not resulting from PRP status). There is evidence of demand for expanded financial reporting disclosure of environmental performance. This demand comes from various interest groups ranging from broad-based public interest to explicit demands by institutional investors. Rockness and Williams (1988) surveyed managers of mutual funds with socially responsible investment objectives. Environmental concerns were the single largest target area of concern within these funds. The results of their survey made it clear that there is a dirth of reliable information on environmental performance. One consequence is the inconsistent evaluations of firms’ environmental performance by managers who must garner evaluative evidence from ad hoc sources. In 1992 the Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC) conducted focus groups and administered a survey instrument to representatives of investment managers, public and private pension funds, banks, insurance companies, universities and church foundations interested in environmental practices of portfolio companies. Participants voiced the opinion that environmental issues “are among the most important challenges companies will need to address in the future”. They view relevant environmental information as critical to assessing portfolio performance. Among the themes running through the focus groups comments are: corporations should be cognizant of what compliance records suggest to stakeholders, the results of environmental audits should be an important source of information to stakeholders, and environmental reporting should convey not only factual information (e.g., emissions) but also the firms’ guiding principles and commitment to environmental stewardship. The research findings identified specific information that is considered important in making investment decisions. Environmental liabilities and environmental expenditures were the most highly sought financial information from the survey participants. The most highly ranked environmental expenditure information is penalty information and capital spending information. Participants comment that a correlation between compliance with environmental statutes and environmental policy is an important cue. While U.S. GAAP somewhat addresses contingent liability reporting through the AICPA’s Statement of Position 96-1, it is wholly silent on reporting environmental expenditure information and/or compliance information. Kreuze, Newell and Newell, (1996) provide evidence that the size of the pool invested in socially responsible funds is substantial and growing. The consistency and reliability of relevant environmental reporting is again raised in this work. Given evident demand for environmental performance disclosure from recognized constituents, the reluctance of accounting standard-setters to develop substantive reporting standards is characterized as resistance to demands for change. This resistance to expanded disclosure is examined from the perspective of the organizational behavior literature that discusses organizational change and resistance to change. Relevant factors that predict change 4 and resistance to change are explored in describing the FASB response. The FASB responses are also examined from the broader perspective of Habermas’ discourse for social action applied against the backdrop of the FASB mission. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is the organization in the United States responsible for developing financial reporting standards. The authority to develop these standards has been delegated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) which retains ultimate oversight authority. For more than a decade and a half there has been demand by a broad cross-section of corporate stakeholders for relevant financial reporting of environmental performance. Although the SEC has adopted substantive reporting requirements for environmental performance for firms whose securities are publicly traded, the FASB has not incorporated equivalent reporting requirements into GAAP. The SEC mandates environmental performance disclosures in Section 103 of Form 10-K by requiring disclosure of administrative and judicial actions brought against firms by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (or other environmental regulatory enforcement bodies) for violation of regulatory statutes. These actions may result from Superfund site exposure, or they may result from current operations. In addition, discussion of the impact of environmental regulations on operations must be discussed in Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A). These disclosure requirements were incorporated into Accounting Series Release 306 (ASR) in 1982. In contrast, GAAP remain within the confines of contingent liability reporting promulgated by FAS 5 applied to environmental uncertainties - largely PRP status under the Superfund laws. The paper is organized in four sections, with the Introduction representing the first. The second section is a review of the organizational behavior literature as it relates to organizational change and organizational resistance to change. The role of discourse and a Habermasian definition of rational behavior during the process of discourse is presented. A brief introduction of discourse applied in economic and sociological settings is provided as a link between Habermas’ philosophy of social action and accounting standard setting. Section three discusses the evidence of demand for environmental performance disclosure in the US. Evidence of pressure applied to the FASB for changes in environmental accounting standards is presented, the outcomes of FASB efforts are reviewed. The context and content of environmental reporting development are described in organizational terms consistent with Laughlin’s (1991) model of organizations. The discourse that has ensued in producing FASB responses is also examined. Section four includes conclusions and further questions raised by the research. LITURATURE REVIEW Organizational Behavior An important theme in the organizational literature is the resistance with which organizations respond to changes in their environments (operating environments, not ecological environments) (Miller and Friesen, 1980a). Miller and Friesen find several basic tenets upon which organizational adaptation can be predicted. Among these tenets is that momentum is a dominant factor, and reversals of the direction of the organization, or in the direction in which demands for change take the organization are relatively rare. The direction of response to demands for change is materially affected by organizational ideologies that focus the organization and its members toward commonly held “world views”. These world views are often built around reinforcing models that make the direction of past 5 responses the likely direction of future responses. The result is that future directions look strikingly similar to existing directions. The trajectory of choice for the future is the existing trajectory along which the organization is already committed. This commitment to directions that already guide the organization arises both from the shared vision of where the organization should go and from the momentum of operations that this vision has created. The authors conclude that in studying the natural resistance of organizations to change, the tendency toward momentum is a primary factor. Organizations develop adaptive patterns that they reuse (Miller and Friesen, 1980b). Over the long run, organizations develop a sort of equilibrium with their surroundings that leads to fairly stable responses to demands for change. Miller and Friesen (1980b) conclude that this set of common response patterns becomes the predictable response to future demands for change. The organization is depicted as in continuous fluctuation between periods of equilibrium (no impending demands for organizational change) and periods of demand for change requiring an organizational response. The response to the state of disequilibrium, where an organizational response is required, is likely to be the familiar pattern of response(s) used on prior occasions. Pettigrew (1987) extends this line of research by examining continuity and change simultaneously; and looking at factors both internal and external to the organization as sources of organizational change. The approach of the research is to see important changes of the organization in terms of the links between the content of change and 1) the (internal and external) context in which the change takes place, and 2) the process by which the organization adapts to demands for change. Pettigrew sees significant organizational change occurring within a “complex analytical, political and cultural process” that successfully challenges the core beliefs held within the organization. He finds these core beliefs provide the frame of reference by which individuals and groups within the organization understand changes in the internal and external environments of the organization. In this Pettigrew’s research supports Miller and Friesen’s findings. Pettigrew goes on to find that there are enormous difficulties in breaking down such core beliefs once a pattern of links between content, context and process becomes embedded in the organization; and examines conditions under which this is successfully accomplished. The results of a long-term organizational case study leads Pettigrew to conclude that organizations go through periods of revolutionary change and evolutionary change. Before radical shifts in organizational content and process can occur, ideological shifts have to take place – the core beliefs must be successfully challenged. Periods when the core beliefs have not been successfully challenged by alternate views are poor internal contexts in which to expect change of a radically different nature. Rather, change in these periods will continue along the trajectory defined by the existing momentum of the organization. The external context of the organization also plays a role, and there are factors that will facilitate or thwart ideological shifts within the organization. The existing dominant ideology is “likely to be rooted in the idea systems that are institutionalized” in the industry in which the organization operates – the external organizational context. Radical shifts within the organization will be retarded by reinforcement of the existing dominant ideology of the external operating environment. On the other hand, changes in the organization’s external context represent a chance to connect new processes and content within the organization to problems newly recognized by the 6 outside world. Therefore, shifts in outer context can facilitate ideological shifts within the organization. Pettigrew concludes that successfully challenging and replacing dominant ideologies is a long-term conditioning process. The challenge for substantive change is “anchoring new concepts of reality, new issues for attention, and new ideas for debate and resolution”. This may be the result of rhetorically creating a perspective that is consistent with the desired direction of change, while at the same time utilizing changes in the external environment as a legitimizing context. While significant insights on the role of context in organizational response are gained from the foregoing literature, Laughlin (1991) contributes important views on the process and content of responding to demands for change. This is viewed from a model for organizations that incorporates intangible as well as tangible aspects, as shown in Figure 1 (Laughlin 1991, 211). The ideologies that orient the organization and its members reside in Level 1. The interpretive schemes of an organization may not be articulated, but they “operate as shared fundamental (though often implicit) assumptions about why events happen as they do and how people are to act in different situations” (Ibid., 212). The design archetypes “are the intervening variable between the higher level values and the tangible sub-systems and are intended to guide the design of the latter to express the perspective of the former” (Ibid.) Figure 1 here Laughlin describes a range of responses of organizations to pressure for change. The implicit preferred choice is for an issue to lack sufficient force to require any response, allowing the organization to maintain its state of inertia. If the force for change is too strong to ignore, some kind of response will be required by the organization. There is a hierarchy of responses available to the organization, representing increasingly greater deviations from the initial state of inertia. Some responses are more desirable to the organization than others. The organization will attempt to respond to the force for change via the preferred response paths, should conditions that unfold in the process of the discourse permit. It is possible, however, that the course of the discourse can force change on the organization and less preferred paths of response may be required. Two levels of response exist within the hierarchy of response options: first-order change and second-order change. First order changes are termed ‘morphostatic’ changes and they represent the ability of the organization to respond to forces of change in form rather than substance. Morphostatic changes leave the interpretive schemes of the organization intact. There are two types of morphostatic responses: rebuttal and reorientation. A rebuttal response is characterized as a response by the organization that declares the issue lacking the imperative for organizational change. A reorientation response is characterized as a recognition by the organization for the need to change (i.e. the force for change cannot be successfully rebutted), but the change undertaken is superficial. Smith (1982) describes morphostatic change as “making things to look different while remaining basically as they have always been” (pp. ). Of these two morphostatic change responses, rebuttal is preferred over reorientation, as it requires the organization to diverge least from its initial state. Second order changes require the organization to alter its essential core of operating and are termed morphogenetic changes. Morphgenetic changes represent responses to forces for change that are so strong that the objectives of the organization (with regard to the specific issue of interest) are successfully altered. The interpretive scheme is altered by these changes. There 7 are also two levels of morphogenetic response available to organizations, and one is preferable to the other. The two levels of morphogenetic change response are colonization and evolution. Laughlin describes colonization as fundamental change coercively imposed on the organization. The implication is that forces outside of the organization have a preference for responding to the issue of interest that is contrary to the preference of the organization, and these external forces have the power to insist on organizational adaptation. Colonization is a less preferable organizational response than evolution, which represents a voluntary adaptation of the organization. Evolutionary change springs from the restatement of the internal values of the organization and results from the process of open discourse on the specific issue of interest. Table 1 presents Laughlin’s framework of organizational change as summarized by Gray et al. (1995, 216). Table 1 here Habermasian discourse Habermas’ theory of social evolution relies on the process of discourse to develop solutions to controversial issues. Discourse is a method of argumentation whereby relevant claims can be debated with the goal of problem solution and/or social progress. Discourse is a method of process. Habermas’ concept of rational behavior extends beyond consideration just of means, or instrumental rationality (e.g., efficiency, utility maximization), to include the cooperative development of ends. He explains rational behavior as reflected in participation in discourse (Habermas 1984, 18): Anyone participating in argument shows his rationality or lack of it by the manner in which he handles and responds to the offering of reasons for or against claims. If he is “open to argument”, he will either acknowledge the force of those reasons or seek to reply to them, and either way he will deal with them in a “rational” manner. If he is “deaf to argument”, by contrast, he may either ignore contrary reasons or reply to them with dogmatic assertions, and either way he fails to deal with the issues “rationally”. Empirical evidence shows discourse is instrumental in developing solutions to economic allocation problems (Kesting 1998, 1054). Kesting explored the role of discourse in three separate economic environmental conflicts in which resource allocations were made. He used rules of discourse based on Habermas’ work and developed by Renn (1995) and Biesecker (1997). He concludes that discourse is a productive means of allocating resources in the context of contentious allocation decisions, and that it serves as an effective economic mechanism of coordination (Kesting 1998, 1074). Because it plays a role in the allocation decisions of economic actors, discourse is an appropriate process for accounting standard-setting which is dedicated to such decisions and decision makers. CONTEXT, PROCESS AND CONTENT OF RESPONSE TO DEMANDS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTING STANDARDS Discourse plays an important role in the formation of consensus and/or conflict resolution both within organizations and between organizations and their external environments. In the case of the organization(s) setting accounting standards, the process of responding to demands for changed (or new) standards relies heavily on discourse. A typical procedure for developing 8 standards includes formation of a task force to develop a statement of the problem. This statement (often in the form of a Discussion Memorandum) is issued for public airing. An Exposure Draft may follow wherein the preliminary version of the standard is proposed and arguments are presented in support. The Exposure Draft is, again, released for public response (Laughlin and Puxty 1983, 461). During these developmental periods, research reports may also feed the discourse. Finally, on the basis of the preceding steps in the process of discourse, the content of response is formulated and a standard or position is issued. The context of accounting standard setting is treated at some length in the critical accounting literature (e.g., Lowe, et al 1983, Merino and Neimark 1982, Laughlin and Puxty 1983, Wildavsky 1994). The social and political contexts of accounting are subjects of inquiry, in addition to the economic context. The context of accounting as a tool of the modern U.S. capitalistic economy dominates the FASB, and represents the governing ideology that orients the organization, as illustrated in the Mission Statement: Accounting standards are essential to the efficient functioning of the economy because decisions about the allocation of resources rely heavily on credible, concise, and understandable financial information. (FASB 1998). It is to be expected, therefore, that the development of accounting standards will take place within an interpretive scheme that is permeated with the values and norms of this economically instrumental framework. Environmental reporting is potentially incongruent with this framework because it often exceeds the boundaries of the normal internal or external exchange transactions traditionally recognized in the accounting model. In addition, corporate environmental performance is the subject of an often-contentious public debate. Environmental activists seek to hold corporate entities responsible for a wide range of environmental impacts, and public interest groups seek more transparency and disclosure of environmental performance. Within academe, green accountants also suggest broadening the traditional accounting framework to incorporate recognition in accounts of environmental ‘transactions’ (Gray, et al 1993). It is expected that the FASB will resist demands for environmental reporting standards that seek to serve ends so alien to the constructs and values of its interpretive scheme. There is evidence of demand for expanded environmental reporting from investors constituents recognized as having legitimate information claims. A growing pool of funds identify socially responsible investments as the primary investment objective (Rockness and Williams 1988, 397; Kreuze, et al 1996, 37). Corporate environmental performance is high on the list of concerns and information needs of these users of financial information. Further, information on environmentally related financial reporting needs and preferences is provided through focus groups and surveys of institutional investors (IRRC 1992). Investors rate environmental liabilities, environmental expenditures, penalty information, and capital spending information the most important financial information that companies should present. Corporate environmental policies and programs are the most important non-financial information needed. In addition, investors want to know whether there is a correlation between corporate environmental goals and accomplishments. Finally, information on compliance with local, state and federal regulatory statues is an important concern to investors. Again, there should be a correlation between corporate environmental policy and objectives, and regulatory compliance (Ibid., v). The foregoing stands as part of the public discourse placing demands on the FASB for 9 expanded environmental reporting. It represents an explicit demand by users of financial statements for expanded environmental reporting. Environmental reporting issues were added to the FASB agenda via the Emerging Issues Task Force on three occasions between 1989 and 1993. EITF 89-13 dealt with asbestos removal costs. The major issues were whether to capitalize or expense these costs, and whether they represented extraordinary expenses. EITF 90-8 dealt with whether to capitalize or expense environmental contamination costs. EITF 93-5 is the most comprehensive of the environmental reporting projects, and addressed accounting for environmental liabilities. This project was incorporated in and effectively nullified by the issuance of Statement of Position (SOP) 96-1 by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the trade association of professional accountants in the United States. SOP 96-1 was issued as an Exposure Draft in June, 1995, and issued as a Statement of Position following due process in 1996. The major issue in this SOP is the application of FASB 5 Contingent Liability treatment to environmental remediation projects. Remediation projects largely result from designation as a Potentially Responsible Party (PRP) on Superfund cleanup sites, and arise from actual or probable legal liability. All of the environmental reporting responses by FASB have been narrow technical applications of existing reporting requirements. The broader public interest issues of reporting corporate environmental performance and the specific preferences of legitimated constituents have not found their way into the standard setting process. Environmental disclosure issues are subordinated to account recognition issues by FASB staff, and are portrayed as (almost) hopelessly fraught with uncertainty. “[I]t follows therefore that questions of disclosure depend to a large degree on the outcome of questions of recognition…” (Johnson 1993, 123). In light of the expressed information preferences of investors, this seems to contradict the spirit of the purpose of disclosure “to describe unrecognized items”, “to provide information to help investors and creditors assess risks and potentials of both recognized and unrecognized items” (Reither 1997, 102). Where in Laughlin’s typology of response to demands for change is this organizational posture cast? Defining the issues very narrowly as recognition of environmental costs and obligations permits organizational rebuttal of calls for disclosure of broader issues. Prescribing reporting requirements that define environmental reporting as another case for application of FASB 5 treatment reorients the rhetoric of the discourse. It permits the appearance of financial reporting that is responsive to a social issue without changing the content of that reporting. Form wins over substance. These responses are consistent with morphostatic responses where the first preference is no response and the second preference is superficial response. FASB standard setting has ignored the information preferences of users in developing environmental reporting standards. This could be understood as an organizational defense against attack by parties interested in radical change, if the only demands for environmental disclosure emanated from groups with no recognized legitimacy. Indeed, a defense might be to question whether we want to upset the capitalist apple cart in favor of ill-defined alternatives (Wildavsky 1994, 480). But demand for environmental disclosure comes from sources which the FASB identifies as having legitimate information needs. Users with impeccable legitimacy credentials are seeking environmental reporting information: investors - and institutional investors, at that. 10 Resistance to demands from this quarter can be understood as organizational failure to deal with an issue whose borders extend beyond the traditional framework of financial reporting. The issue challenges the interpretive scheme of accounting standard-setting organizations. The responses have been, predictably, those which require the least diversion from the established pattern of existing standards, even though this cheats on the stated mission and goals of the organization. The weak correlation between the need for information on contemporary issues of broad public interest, and the responsiveness of accounting standard-setters has been the subject of periodic Congressional inquiry for over two decades. FASB has recently been criticized for the low level of public participation in standard setting (GAO 1996, 4-5). User’s need are ignored in spite of their declared importance in the mission and goals of the organization, and in spite of the open discourse process of standard setting. The lack of public participation in environmental reporting standard setting, and the dogmatic reasoning displayed in the discourse show the FASB to be “deaf to argument”. The claims for environmental information disclosure have either been ignored or dismissed with dogmatic assertions that “most questions about disclosure must necessarily await the outcome of questions about recognition” (Johnson 1993, 123). These responses indicate irrational behavior in a discourse dedicated to problem solution or progress (Habermas 1984, 18). CONCLUSION Several conclusions can be drawn from this analysis. First, environmental reporting needs to be more responsive to user needs. Thus far, environmental standard setting has been a repackaging of existing reporting standards with the term ‘environmental’ inserted at strategic points in the discourse. This is consistent with morphostatic change using a reorientation response strategy. Second, without substantive expansion of environmental reporting standards public confidence in responsive standard setting by the accounting profession weakens. This continues to provide fodder for charges (like those made by the GAO) that standard setting lacks a balanced perspective in meeting user needs. There have been calls within academe, as well, for reporting standards responsive to matters of broad public interest for well over two decades (Parker, 1986). Environmental reporting is currently one such broad-based issue. Standard-setters responses have not acknowledged or incorporated into serious discourse the information preferences of recognized constituents. The response of professional standard setting bodies has been predictable from the organizational behavior view, and disappointing from the perspective of the credibility of those same institutions. The sincerity of the discourse is sacrificed to organizational inertia. 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY AICPA Special Committee on Financial Reporting. 1994. Improving Business Reporting - A Customer Focus: Meeting the Information Needs of Investors and Creditors. New York, NY: AICPA. AICPA. 1996. Statement of Position 96-1 “Environmental Remediation Liabilities”. New York, NY: AICPA. Biesecker, Adelheid. 1997. “The Market as an Instituted Realm of Action”. Journal of SocioEconomics. 26 (3): 215-241. FASB. 1989. EITF 89-13 “Costs of Asbestos Removal”. Norwalk, CT. FASB. FASB. 1990. EITF 90-8 “Capitalization of Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination”. Norwalk, CT. FASB. FASB. 1993. EITF 93-5 “Accounting for Environmental Liability”. Norwalk, CT. FASB. FASB. “The Mission of the Financial Accounting Standards Board”. Http: //www.rutgers.edu/ Accounting/raw/fasb/facts/fasfact1.html. September 19, 1998. General Accounting Office 1996. “The Accounting Profession: Major Issues Progress and Concerns”. Report to the Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Commerce, House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: GAO Gray, R., Jan Bebbington and Diane Walters. 1993. Accounting for the Environment. New York, NY: Markus Wiener Publishing Inc. Gray, R., Diane Walters, Jan Bebbington and Ian Thompson. 1995. “The Greening of Enterprise: An Exploration of the (Non) Role of Environmental Accounting and Environmental Accountants in Organizational Change”. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 6: 211-239. Habermas, Jurgen. 1984. Theory of Communicative Action. Thomas McCarthy, translator. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Investor Research Responsibility Center (IRRC). 1992. Institutional Investor Needs for Corporate Environmental Information. Washington, D.C. IRRC. Johnson, L. Todd. 1993. “Research on Environmental Reporting”. Accounting Horizons 7(3): 118-123. Kesting, Stefan. 1998. “A Potential for Understanding and the Interference of Power: Discourse as an Economic Mechanism of Coordination”. Journal of Economic Issues 32 (4): 10531078. 12 Kreuze, Jerry G., Gale E. Newell, and Stephen J. Newell. 1996. “What Companies Are Reporting”. Management Accounting July 1996: 37-43. Laughlin, Richard C. and Anthony G. Puxty. 1983. “Accounting Regulation: An Alternative Perspective”. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 10 (3): 451-479. Laughlin, Richard C. 1987. “Accounting Systems in Organizational Contexts: A Case for Critical Theory”. Accounting, Organizations and Society 12 (5): 479-502. ________ 1991. “Environmental Disturbances and Organizational Transitions and Transformations: Some Alternative Models”. Organization Studies 12 (2): 209-232. Lowe, E.A., A.G. Puxty and R.C. Laughlin. 1983. “Simple Theories for Complex Processes: Accounting Policy and the Market for Myopia”. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2: Merino, B.D. and M.D. Neimark. 1982. “Disclosure Regulation and Public Policy: A Sociohistorical Reappraisal”. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy (1) pp. 33-57. Miller, Danny and Peter H. Friesen, 1980a. “Momentum and Revolution in Organizational Adaptation”. Academy of Management Journal 23 (4): 591-614. ________, 1980b. “Archetypes of Organizational Transition”. Administrative Science Quarterly 25 (June): 268-299. Parker, Lee D. 1986. “Polemical Themes in Social Accounting: A Scenario for Standard Setting”. Advances in Public Interest Accounting Vol. 1: 67-93. Pettigrew, Andrew M. 1987. “Context and Action in the Transformation of the Firm”. Journal of Management Studies 24 (6): 649-670. Renn, Ortwin, Thomas Webler, and Peter Wiedemann, eds. 1995. Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse. Dordrecht, Boston, and London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Reither, Cheri L. 1997. “How the FASB Approaches a Standard-Setting Issue”. Accounting Horizons 11(4): 91-104. Roberts, Richard Y. 1995. Comments of SEC Commissioner to “Critical Environmental Issues for Corporate Counsel Conference”. SEC http://www.sec.gov/ Rockness, Joanne and Paul F. Williams 1988. “A Descriptive Study of Social Responsibi8lity Mutual Funds”. Accounting, Organizations and Society 13 (4): 397-411. 13 Securities and Exchange Commission. 1982. Accounting Series Release No. 306. 17 CFR. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office. Smith, K.K., 1982. “Philosophical Problems in Thinking About Organizational Change” in P.S. Goodman et al. (eds.), Change in Organizations, Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA: pp. 316-374. Wildavsky, Aaron, 1994. “Accounting for the Environment”. Accounting, Organizations and Society 19 (4/5): 461-481. 14 Figure 1 Organizational Design Archetype Level11 Level Beliefs, Values and Norms Interpretive Schemes Intangible Level Level2 Mission/Purpose Level 3 Metarules Le Balance/coherence Design Archetype Organization Structure, Decision Processes, Communication System Tangible Table 1 Laughlin’s typology of organizational change No change (i) Inertia First order change (morphostatic) (ii) Rebuttal (iii) Reorientation Second order change (morphogenetic) (iv) Colonization (v) Evolution