Hamlet's Fathers: An Analysis of Paternity and Filial

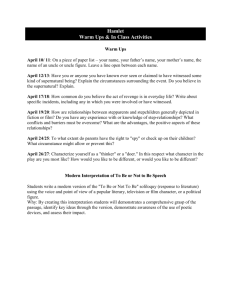

advertisement