Clinical Oncology (2004) 16: 523–527

doi:10.1016/j.clon.2004.06.024

Original Article

Small-cell Carcinoma of the Urinary

Bladder: 10-year Experience

S. A. Mangar*, J. P. Logue*, J. H. Shanksy, R. A. Cooperz, R. A. Cowan*, J. P. Wylie*

*Department of Clinical Oncology, Christie Hospital NHS Trust, Manchester; yDepartment of Histopathology, Christie

Hospital NHS Trust, Manchester; zDepartment of Clinical Oncology, Cookridge Hospital, Leeds, UK

ABSTRACT:

Aims: Small-cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder is rarely encountered in clinical practice. We report on our clinical experience with

affected patients presenting to our institution from 1986 to 1996.

Materials and methods: We retrospectively analysed 14 pathologically confirmed cases, specifically looking at stage, presenting features,

treatment and overall survival. The median age at presentation was 74 years (range 54–91 years).

Results: Ten patients presented with stage III disease, and four patients with stage IV disease (1 Z nodal, 3 Z distant metastases). Four

patients were treated with radical radiotherapy (one patient receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy) and two underwent a radical

cystoprostatectomy. Five patients received palliative bladder radiotherapy and three were too frail for treatment at presentation. The overall

median survival was 5 months. Patients receiving radical treatment had a median overall survival of 21 months, with only one long-term

survivor.

Conclusion: This highly aggressive tumour tends to affect an elderly population who are generally frail and have significant comorbidity.

Many are unfit for radical treatment. In patients with disease confined to the pelvis who are able to tolerate radical intervention, the results

of local therapy alone are poor. It therefore remains incumbent on treating clinicians to explore means of improving these results. Initial

chemotherapy analogous to small-cell lung cancer may offer a durable response with a better chance for long-term survival. Mangar, S. A.

et al. (2004). Clinical Oncology 16, 523–527

Ó 2004 The Royal College of Radiologists. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Key words: Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, small-cell bladder cancer

Received: 21 January 2004

Revised: 20 May 2004 Accepted: 23 June 2004

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma is a rare but welldescribed tumour occurring at sites as diverse as the

gastrointestinal tract, thymus, larynx, salivary gland, skin,

breast, prostate and cervix [1–8]. Within the urinary

bladder, it accounts for less than 0.5% of malignancies

[9]. Since the first published case by Crameret al. [10] in

1981, about 150 cases have been reported to date [11].

With such paucity of clinical data, it is not possible to

offer a didactic approach to treatment. Many of the reported

cases present with either locally advanced or metastatic

disease, and most patients ultimately die of disseminated

disease. We report our clinical experiences with 14 patients

treated at this institute, and review the published literature

about the management of this disease.

All cases (n Z 14) of small-cell carcinoma of the urinary

bladder (SCBC) referred to the Christie Hospital, Manchester, UK from 1986 to 1996 were retrospectively

reviewed. Data on age, sex, presentation, stage, treatment

and outcome were obtained from the medical notes.

Certified causes of death were obtained from the National

Cancer Registry. All patients had an initial transurethral

resection (TUR). All pathology was reviewed centrally. For

those patients in whom radical treatment was intended,

computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, and

chest radiographs, were obtained. The time to relapse was

calculated from the date of diagnosis, and absolute survival

figures are quoted. Where possible, patients were staged

according to the UICC TNM 1987 classification.

Results

Author for correspondence: Dr S. Mangar, Academic Department of

Radiotherapy, Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5PT, UK;

Tel.: 0208-661-3261; Fax: 0208-643-8809; E-mail: stephenmangar@

supaworld.com

0936-6555/04/080523C05 $35.00/0

The clinical details are summarised in Table 1. Twelve men

and two women with a median age of 74 years (range 54–

91 years) were treated within the 10-year study period. The

Ó 2004 The Royal College of Radiologists. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

524

CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Table 1 – Summary of patient details

Age

(years)

Stage*

1; male

70

T3N0M0

Radical bladder radiotherapy

2; male

3; female

81

91

T3

T3

4; male

86

T3, M1

5; male

6; male

62

79

pT3N0M0

T4N0M0

7; male

58

T3N0M0

8; male

85

T3N0M0

9; male

10; male

11; female

81

64

84

T3N1M0

T3N0M0

M1

Palliative bladder radiotherapy

Too frail

for treatment

Too frail

for treatment

Cystoprostatectomy

Palliative bladder

radiotherapy

Induction chemotherapy

( platinum/etoposide)

Radical bladder radiotherapy

Palliative bladder

radiotherapy

Palliative bladder radiotherapy

Radical bladder radiotherapy

Palliative bladder radiotherapy

12; male

65

T4N0M0

Radical bladder radiotherapy

13; male

74

M1

14; male

54

pT3N0M0

Too frail

for treatment

Cystoprostatectomy

Patient; sex

Treatment

Site of relapse/further treatment

Neck nodes at 14 months/six

cycles of platinumchemotherapy

Brain metastases at 22 months/cranial

radiotherapy

Outcome

Cancer death at 24 months

Cancer death at 4 months

Cancer death at 1 month

Clinical evidence of brain metastases

at presentation

Cancer death at 2 weeks

Cancer death at 4 months

Cancer death at 18 months

Para-aortic lymph nodes at

15 months/abdominal

radiotherapy

Bone metastases at 5 months

Bone metastases

at presentation

Liver and bone

metastases at 4 months

Bone metastases

at presentation

Cancer death at 18 months

Cancer death at 9 months

Cancer death at 3 months

Intercurrent death at 39 months

Cancer death at 4 months

Cancer death at 6 months

Cancer death at 2 months

No clinical evidence of

disease at 7 years

*Staging according to UICC TNM 1987. In some cases, there is insufficient information to give complete TNM stage.

most common presenting symptom was haematuria in 13

patients. One patient presented with urinary frequency. Of

the nine completely staged patients, eight presented with

stage III disease (T3N0-6, T4N0-2), and one with a stage

IV tumour (T3N1M0). Five patients were too frail at

presentation to undergo full staging investigations. Three

patients presented with distant metastasis.

Two patients had a previous history of malignancy. Case

11 had an invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the

bladder treated with radiotherapy 21 years earlier, and case

eight had an early stage prostatic adenocarcinoma diagnosed but not treated 9 years previously.

The most frequent site of involvement within the bladder

was on the lateral and posterior walls. The lesions were

invariably unifocal and had a predominantly papillary

morphology. The pathology findings are summarised in

Table 2. One case was negative for both cytokeratins, and

five cases were negative for both chromogranin and

synaptophysin. In 12 cases, there were elements other than

small-cell carcinoma present (Table 3).

All treatment was at the discretion of the treating

clinician. Three patients were too frail for any further

treatment following TUR. Of these, one had bone

metastases at presentation and one had suspected cerebral

metastases. Five patients were treated with palliative

radiotherapy to the pelvis, and four received radical

radiotherapy to the bladder. The radical dose given was

50–52.5 Gy/20 fractions using megavoltage photons

planned as a four-field brick covering the whole bladder

with a 1.5 cm margin. One of these patients received

treatment with six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy

(carboplatin AUC 5, and etoposide 120 mg/m2 d1–3)

before radical radiotherapy, and another patient received

the same chemotherapy regimen at relapse. Two patients

had a radical cystoprostatectomy.

Overall, 10 (70%) patients died of disease within 2 years

of diagnosis (median overall survival 5 months). Eight died

Table 2 – The panel of immunohistochemical markers

Detectable antigen

Chromogranin

Synaptophysin

Neuron-specific enolase

MIC-2

CAM 5.2 (cytokeratin)

MNF 116

MIC-2 (CD99 antigen);

CAM 5.2 (cytokeratin 7C8);

MNF 116 (cytokeratin 6, 16, 17).

Positive

Negative

8

6

14

0

12

10

6

8

0

14

2

4

525

SMALL-CELL CARCINOMA OF THE URINARY BLADDER

Table 3 – The presence of other histological elements

Histological elements other than small-cell

carcinoma present (n Z 12)

5

5

4

Flat surface dysplasia or carcinoma in situ

Transitional cell differentiation

Focal glandular differentiation

Note that the above categories were not mutually exclusive.

within 6 months of presentation. The 2-year cancer-specific

death rate was 86% overall, and 70% for those receiving

local treatment. The only intercurrent death was in a patient

who died of heart failure at 39 months after radical

radiotherapy, with no evidence of recurrence. The six

radically treated patients had a median overall survival of

21 months, with one patient remaining alive, with no

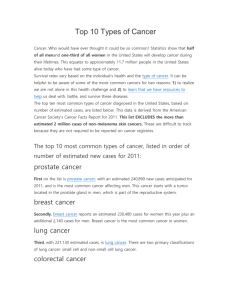

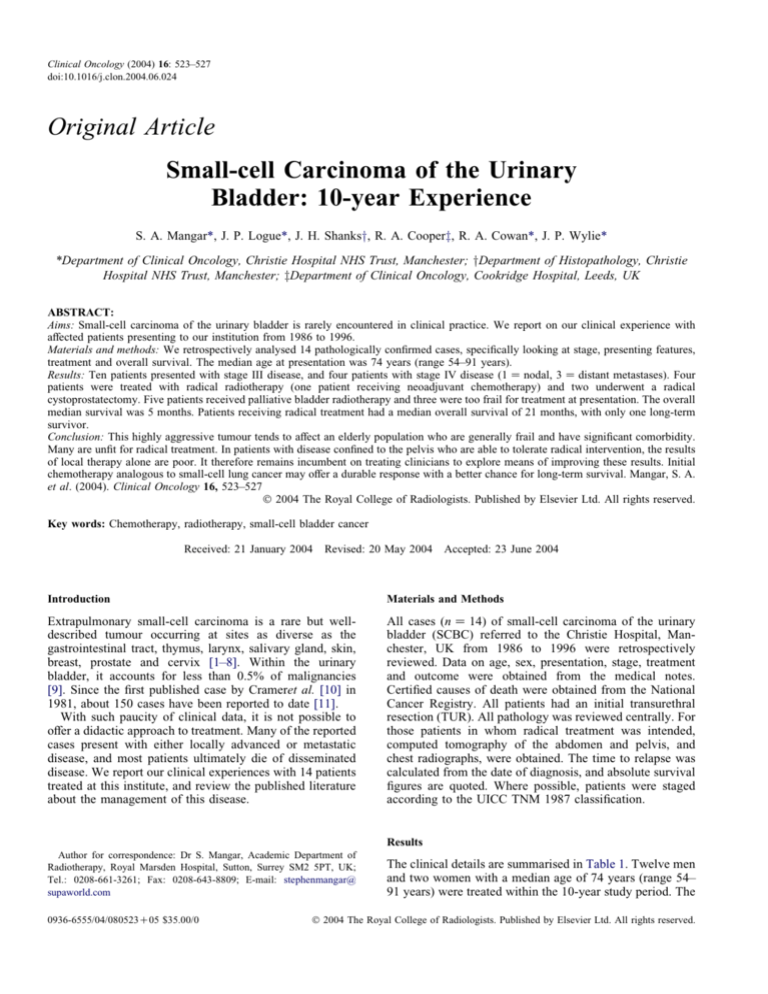

evidence of disease, 7 years after a radical cystoprostatectomy. The relationship between stage and overall survival

is shown in Fig. 1. The sites of relapse were varied and

included liver, brain, bone and lymph nodes.

Discussion

Primary small-cell carcinoma occurs at several sites along

the urinary tract [12], but the bladder is the most frequently

reported [13]. Bladder metastases from small-cell lung

cancer (SCLC) [14] are described, but are normally

associated with widely disseminated disease and should

be easily identified with staging investigations.

The pathology of SCBC is similar to that of SCLC.

There is normally positive staining for cytokeratin and

neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin, synaptophysin, or

both) [15]. However, as our study shows, these can

occasionally be negative. Neuron-specific enolase is almost

always positive, although this marker is not regarded as

specific. However, our study and others [15,16] have shown

that, unlike SCLC in SCBC, there is a higher proportion of

mixed small-cell and non-small-cell carcinoma. The nonsmall cell elements are typically urothelial or glandular,

with or without carcinoma in situ.

In keeping with other reports, this series confirms the high

propensity for metastatic spread and early death shown by

SCBC [15–17]. Three patients were so debilitated at

presentation that no treatment could be offered, and only

two patients were alive and disease-free 2 years after

treatment. Outcome is related to stage, and no patients with

stage IV disease survived beyond 6 months, with a median

survival of only 2 months in patients with extrapelvic

metastasis. Abbas et al. [7] compiled all the published cases

of SCBC in 1995, and estimated a 25% 2-year survival and

8% 5-year survival for patients with disease confined to the

pelvis. Although various treatment approaches were used,

most of the patients did not receive chemotherapy.

The correct treatment strategy for this rare tumour

remains unclear. However, there are analogies, in histology

and natural history, to SCLC where regimens containing

platinum are standard [18,19]. Review of the published

literature certainly suggests improved outcome when

chemotherapy is added to the local treatment of SCBC.

Dalpiaz et al. [20] analysed data on 139 reported cases.

Although the median survival was only 13 months, there

seemed to be an improved survival in people receiving

additional chemotherapy.

Blomjous et al. [15] reported five patients, predominantly

with advanced stage disease, who received chemotherapy

after local treatment. Various chemotherapy combinations

were used, but most were platinum-based. All ultimately

relapsed, but the median survival at the time of reporting

was 22 months. Grignon et al. [16] reported a series of 22

cases, of which eight received chemotherapy either as their

sole treatment or combined with cystectomy (63%) or

radiotherapy (13%). About 90% had advanced stage

(OT3b) disease. The precise details of scheduling of the

chemotherapy are not given, although combinations

containing platinum were used in most cases. Patients

Proportion alive (%)

100

80

T3

T4

60

Overall survival

Metastatic

40

20

0

0

10

20

Time (months)

30

40

50

Fig. 1 – Treatment outcomes: the relationship between stage and overall survival. Overall survival for all stages is compared with survival

according to specific stage at presentation.

526

CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

receiving chemotherapy had longer disease-free intervals

(range 10–77 months) compared with the remainder of the

group (range 1–28).

More recently, Lohrisch et al. [21] reported their experiences using chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both, for 10 out

of 14 eligible patients presented to the British Columbia

Cancer Agency between 1985 and 1996. All patients had

disease confined to the pelvis. Four patients received three

to four cycles of chemotherapy, followed by local

radiotherapy; an equal number had concurrent chemoradiotherapy (the exact timing was not clearly documented)

after TUR. The remaining two patients were treated with

chemotherapy alone. The most commonly used regimen

was etoposide and cisplatin. The use of concurrent

chemoradiotherapy was not associated with an increase in

local morbidity. The 2- and 5-year actuarial survival for the

10 patients was 70% and 44%, respectively. These

impressive results, albeit for a selected group of patients,

provide optimism for a chance of long-term survival for

individuals with limited stage disease.

In deciding optimal local treatment, there are no direct

comparisons between cystectomy and radical radiotherapy.

Some investigators have suggested that cystectomy may be

preferred [16,22,23]. Dalpiaz et al. [20] reported that the

combination of surgery and chemotherapy resulted in 70%

of patients alive at median follow-up of 20 months

compared with 54% for patients receiving chemotherapy

and radiotherapy. Selection bias may explain these results.

By offering initial cystectomy, there is genuine concern that

chemotherapy will be delayed until the patient has sufficiently recovered. Using the analogy of SCLC, initial

chemotherapy followed by radical radiotherapy may be preferred. Within our series, isolated local recurrences occurring after radiotherapy seem rare, with only one case seen

in a patient who received palliative bladder radiotherapy.

Unfortunately, despite these presumed advantages to

using chemotherapy, this approach was not possible in most

patients reported in our series. Many of the patients were

elderly and frail as a result of their cancer, intercurrent

illness, or both, and were felt to be unlikely to tolerate

chemotherapy. Another concern is that patients may have

impaired renal function due to the site and bulk of their

disease, and this is likely to hamper administration of

nephrotoxic chemotherapy, such as cisplatin. Even simpler

chemotherapy schedules recommended for frail patients

with SCLC [24] may be too toxic in this particular group.

Conclusion

Small-cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder is a rare

tumour, and agreed treatment protocols are lacking. The

experiences of this and other series suggest that this is an

aggressive tumour that usually presents with an advanced

stage, with a pattern of spread similar to pulmonary smallcell carcinoma. Treatment schemes may be derived from

the analogy with SCLC. In suitably fit patients, we would

therefore recommend platinum-based chemotherapy followed by bladder radiotherapy if appropriate. However,

most patients present in such a frail state that this approach

will not be feasible, and palliative pelvic radiotherapy for

local symptom control would be more appropriate accepting that the patient is likely to soon develop disseminated

disease.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to thank Mr N Clarke

and Mr V Ramani for help in providing the necessary database, and the

departments of Medical Illustration and Kostoris Library- Christie Hospital

for helping to research and prepare the manuscript. Acknowledgements

also to F Power, I Mangar, and R Mangar for their help in the final

preparation of this article.

References

1 Sarma DP. Oat cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. J Surg Oncol 1982;

19:145–150.

2 Wick MR, Schiethauer BW. Oat cell carcinoma of the thymus. Cancer

1982;49:1652–1657.

3 Porto DP, Wick MR, Ewing SL, Adams GL. Neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the larynx. Am J Otolaryngol 1987;8:97–104.

4 Gnepp DR, Wick MR. Small cell carcinoma of the major salivary

glands. An immunohistochemical study. Cancer 1990;66:185–192.

5 Taxy JB, Ettinger DS, Wharam MD. Primary small cell carcinoma of

the skin. Cancer 1980;46:2308–2311.

6 Yogore MGD, Saghal S. Small cell carcinoma of the male breast:

report of a case. Cancer 1977;39:1748–1751.

7 Abbas F, Civantos F, Benedetto P, Soloway MS. Small cell carcinoma

of the bladder and prostate. Urology 1995;46:617–630.

8 Sykes AJ, Shanks JH, Davidson SE. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine

cervix: a clinicopathological review. Int J Oncol 1999;14:381–386.

9 Blomjous CE, Thunnissen FB, Vos W, deVoogt HJ, Meijer CJ. Small

cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evaluation of three cases with a review

of the literature. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1988;413:

505–512.

10 Cramer SF, Aikawa M, Cebelin M. Neurosecretory granules in small

cell invasive cancer of the urinary bladder. Cancer 1981;47:724–730.

11 Alcala JA, Ripa Saldias L, Aldave Vllanueva J, et al. Neuroendocrine

small cell carcinoma of the bladder. Review of the literature and review

of a case. Arch Esp Urol 2002;55:452–456.

12 Morgan KG, Banergee SS, Eyden BP, Barnard RJ. Primary small cell

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the kidney. Ultrastruct Pathol 1996;20:

141–144.

13 Wu TT, Lee YH, Huang JK. Primary small cell carcinoma of the

urinary bladder: report of a case. J Formos Med Assoc 1995;94:

576–577.

14 Coltart RS, Stewart S, Brown CH. Small cell carcinoma of the

bronchus: a rare cause of haematuria from a metastasis in the urinary

bladder. J R Soc Med 1985;78:1053–1054.

15 Blomjous CE, Vos W, deVoogt HJ, Van der Valk P, Meijer CJ. Small

cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. A clinicopathologic, morphometric, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of eighteen

cases. Cancer 1989;64:1347–1357.

16 Grignon DJ, Ro JY, Ayala AG, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the

urinary bladder. A clinicopathological analysis of twenty two cases.

Cancer 1992;69:527–536.

17 Holmang S, Borghede G, Johansson SL. Primary small cell carcinoma

of the urinary bladder: a report of 25 cases. J Urol 1995;153:

1820–1822.

18 Spiro SG, Souhami RL, Geddes DM, et al. Duration of chemotherapy

in small cell lung cancer: a cancer research campaign trial. Br J Cancer

1989;59:578–583.

19 Bleehan NM, Girling DJ, Machin D, Stephens RJ. A randomised

trial of three or six courses of etoposide, cyclophosphamide

methotrexate and vincristine or six courses of etoposide and

ifosfamide in small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1993;68:1150–

1156.

20 Dalpiaz O, Al Rabi A, Galfono A, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the

bladder: a case report and literature review. Arch Esp Urol 2003;56:

197–202.

SMALL-CELL CARCINOMA OF THE URINARY BLADDER

21 Lohrisch C, Murray N, Pickles T, Sullivan T. Small cell carcinoma of

the bladder. Long term outcome with integrated chemoradiation.

Cancer 1999;86:2346–2352.

22 Oesterling JE, Brendler CB, Burgers JK, et al. Advanced small cell

carcinoma of the bladder. Successful treatment with combined radical

cystoprostatectomy and adjuvant methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubacin and cisplatin chemotherapy. Cancer 1990;65:1928–1936.

527

23 Podesta AH, True LD. Small cell carcinoma of the bladder. Report of

five cases with immunohistochemistry and review of the literature with

evaluation of prognosis according to stage. Cancer 1989;64:710–

714.

24 Girling DJ. Comparison of oral etoposide and standard intravenous

multidrug chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer: a stopped multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 1996;348:559.