Inequality, Ethnicity and Social Disorder in Peru.

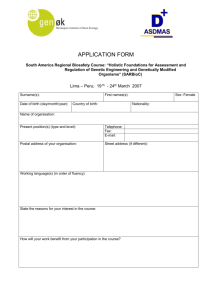

advertisement