Comparative Ideas of Chronology

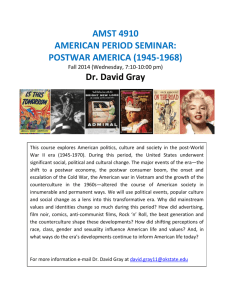

advertisement