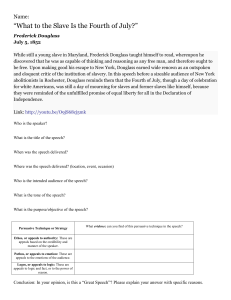

American Law Review - American University Law Review

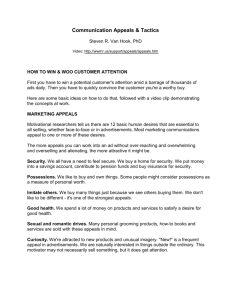

advertisement