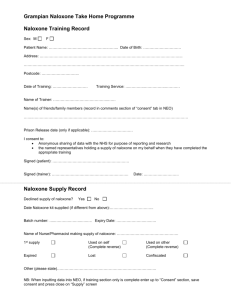

Service Evaluation of Scotland's National Take

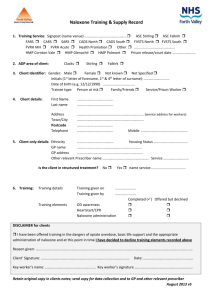

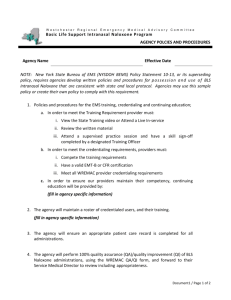

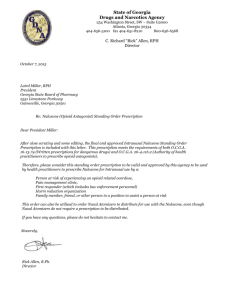

advertisement