Friday Sermons and the Question of home

advertisement

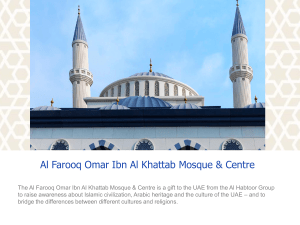

Australian eJournal of Theology 19.1 (April 2012) Friday Sermons and the Question of home-trained Imams in Australia Ismail Albayrak Australian Catholic University Abstract: Imams in the mosques wield a considerable amount of influence within the diverse Muslim communities in Australia. Similarly to Western Europe, requests have recently been made for imams to be trained in Australia. The question is, ‘Can imams who have come to Australia from various overseas countries which do not have proper democracies, and who thus face both language and cultural barriers, communicate Australian values to young Australian-born Muslims through their sermons and leadership?’ Many think that there is only one proposed solution, namely producing home-trained Australian imams. This article investigates this demand in the light of Friday sermons delivered in two major mosques in Melbourne. It also argues that there is no single institution in Australia for training imams. Bearing in mind the diverse nature of Muslim communities, this article suggests that, through the establishment of an advisory body via the collaboration of various Australian organisations, these imams from overseas should participate in short but concentrated programs to make them more familiar with Australian values, multiculturalism, integration, inter-faith dialogue, and common moral and ethical issues. Key Words: Imams, Friday sermons, ethics, training 1. INTRODUCTION Australians are now aware of al-Shabab, an Al-Qaeda-like terrorist group whose members planned an attack on Sydney's Holsworthy army barracks in 2009. Subsequent newspaper reactions generally focused on the need for a more intensive screening of immigrants for potential terrorist threats. While it does not seem that discussions about home-grown terrorism and immigrant terror threats will disappear any time soon, Victorian MP Adem Somyurek’s analytical article draws attention to a different aspect of the topic. 1 In summary, Mr Somyurek questions how imams in Australia, most of whom have come from non-democratic countries, and face both language and cultural barriers, can possibly communicate Australian values to young Australian-born Muslims. 2 In other words, Somyurek points out that imams, who are supposed to guide their congregations in the mosque on how to respond and adapt to their new country, are Adem Somyurek, “Home-grown Muslim role models can help turn tide of hate”, The Age (11 August 2009). The expression ‘Australian values’ is a very generic one, and here simply refers to a genuine commitment to coming to an understanding of the way of life in Australia, together with strong sense of belonging to Australia. I do believe that Australian imams, by their presence, play a significant role in encouraging their communities to contribute to the mosaic of Australian society. 1 2 29 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons themselves trained far away from Australia. As a solution, Mr Somyurek suggests that Australia needs to train and produce its own imams who can relate to young Australians and can communicate Australian values effectively. Such a recommendation is not unique to Australia. Indeed, almost every country in Europe has debated fiercely on this important topic. Both government officials and NGOs have made various requests to be able to train imams locally in the country in which they are to work. Interestingly enough, in some countries there have been local initiatives to start the local training of imams. 3 In this article, I would like to question the readiness of Australia to start training imams. I will focus my argument on the status of the Friday sermon (khutba) and the general characteristics of sermons in two central mosques in Melbourne. I include an analysis of the content of the sermons. Finally, I will relate my findings to Mr Somyurek’s well-intentioned recommendations in order to demonstrate that these recommendations are unrealistic and impractical within the context of existing Australian institutions. At this point, I do not intend to engage in an analysis of the complex relationship that exists between state and church. 2. THE STATUS OF THE KHUTBAS (FRIDAY SERMONS) IN ISLAM Although we do not come across the word khutbah in the Qur’an, we frequently see the expression in the prophetic traditions. However, it is important to note that the oral communication of traditions was part and parcel of the Arabian society long before Islam, and early Muslims continued this way of communication in their daily life. Many Muslim jurists consider the expression ‘remembrance of God’ in verse 62:9 — ‘O ye who believe! When the call is heard for the prayer of the day of congregation, hasten unto remembrance 4 of God and leave your trading’ — as the incentive for the Friday sermon, khutbah. There have been various discussions among Muslim scholars as to the nature, content and language of the sermon (whether in Arabic or any other language), as well as on the number of addressees, and the exact time of delivering the sermon. At this juncture, such juristic details are not relevant to our topic; suffice to say that Friday sermons are an inseparable part of the Friday prayer, and therefore Muslims take them very seriously. When we consider the sermons of the Prophet, and of the early caliphs and the sages, we realise that their scope was vast. Thus, it is inaccurate to think of these sermons solely from a religious perspective, since, in addition to their focus on the ethical and religious formation of the community, they also play a significant role in uniting the community both socially and politically. For this reason, it has been common for caliphs throughout history to ask officials to read sermons on their behalf, in order to display the sovereignty 5 of the caliph and the state. Consequently, sermons also became a reflection of political 3 See Jean-François Husson, “Training Imams in Europe: The Current Status”, King Baudouin Foundation 2007. Online: http://www.kbs-frb.be/uploadedFiles/KBSFRB/05)_Pictures,_documents_and_external_sites/09)_Publications/PUB_1694_TrainingImamsEurope.pdf (accessed January 20, 2011); Niels Sorrells, “Germany experiments with training, certifying imams who interpret Europe for immigrants”, Religion News Service 2010. Online: http://www.cleveland.com/world/index.ssf/2010/12/germany_experiments_with_train.html (accessed March 10, 2011). France and Germany are two important examples in this regard. I personally believe in benefiting from the experiences of other countries, but one should not disregard country-specific circumstances. 4 Abu Bakr Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Sarakhsi, al-Mabsut (Beirut: Dar al-Ma’rifah, 1989) vol. 2, 120. Mustafa Baktır, ‘Hutbe’, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi (İstanbul: Diyanet Vakfı Pub, 1998), Vol, 18, 425-8: at 426. 5 30 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons power. Be that as it may, Friday sermons today continue to have a special religious status among Muslims, and attendees are forbidden to speak among themselves during the delivery of sermons. 6 Sermons require absolute silence and only the imam can speak; anyone else who speaks, or even asks another person not to speak, is acting against Islamic law. This brief explanation demonstrates the importance of sermons and the way in which they effectively convey messages to attendees. 3. ANALYSIS OF FRIDAY SERMONS 3.1. Preliminary observation It is important to note that the Muslim community in Australia is not a united entity. We should therefore speak of Muslim communities, for Muslims come from many different countries and diverse backgrounds. While Islam is the general umbrella term under which these communities are gathered, Muslims from different cultures and nationalities naturally have similar but distinctive features. I would like to share my own experiences, having attended the Friday prayers and sermons regularly at two different Melbourne mosques over the past two and a half years. During the first year (January 2008–December 2008), I regularly attended a centrally located mosque in Broadmeadows, which has a majority-Turkish congregation. 7 The following year (December 2008–April 2010), I attended the Preston Mosque (the actual name of the mosque is Masjid Umar b. al-Khattab), which has an Arab-majority congregation. The former official Mufti of Australia, 8 Shaykh Fahmi al-Imam, attends the Preston Mosque regularly, and offers sermons there from time to time. I listened to a total of 42 sermons at the Broadmeadows Mosque and 44 sermons at the Preston Mosque. Nearly 1400 Muslims congregate at the Broadmeadows Mosque 9 while 1200 Muslims 10 congregate at the Preston Mosque. The sizes of these congregations clearly indicate that the imams can wield a considerable degree of influence within their communities. During the two and half years of my attendance at these two mosques, I discovered some differences between the two Muslim communities and the challenges facing the imams, who need to be aware of and relate to the various needs and cultures. The Friday sermons at the Preston Mosque are often offered by imams from Lebanon and various other Arab nations, who are brought to Australia by the Mosque committee. The Broadmeadows Mosque, with its largely Turkish congregation, has an imam who is assigned by the Presidency of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Turkey. These imams are normally assigned for a period of about four years, after which the serving imam is replaced. Abu al-Husayn al-Hajjaj al-Muslim, al-Sahih, Bab fi al-insat yawm al-jum’ah,( Riyad: Dar Tayba, 2006) vol. 1, 382) 7 I missed some of the Friday sermons during this period because I went overseas several times. 6 The new Grand Mufti of Australia is Dr. Ibrahim Abu Muhammad. It is important to note that the same topic and sermon are delivered by other Turkish imams in seven different Turkish mosques around Victoria. Thus, more than 3000 people across Victoria actually listen to each sermon. 10 We have not considered Shi’ite Muslims, as they constitute a very small minority of the Muslims in Australia. This topic, I think, requires further study. 8 9 31 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons The imams and preachers who offer sermons at the Preston Mosque have had extensive religious training and education in their country of origin, through either traditional methods or a university education. As a result, they are confident and aware of topics relating to Islamic traditions. In addition, the majority of them recite the Qur’an excellently. Their preparation and training are not the result of merely a couple of years’ education, but reflect many years of growing in knowledge and practising their religion. 11 Consequently, these imams and preachers are able to answer questions put to them by their congregations meaningfully and rationally. The Turkish imams come from somewhat different educational backgrounds. They are graduates of Theology faculties of universities in Turkey and, on the completion of their degrees, undergo a specific three-year training program set up by the Presidency of Religious Affairs. Their education is comprehensive, and they have a good deal of experience. They also receive regular support from the Turkish Attaché who is responsible for the social and religious affairs of the Turkish community in Melbourne. While sermons are usually long at the Preston Mosque, short sermons are the order of the day at the Broadmeadows Mosque. Sermons also include poems and proverbs from 12 the respective cultural backgrounds of the imams. The Broadmeadows Mosque offers its sermons first in Turkish, then in English, whereas the Preston Mosque offers its sermons first in Arabic, then in English. As the imam at the Broadmeadows Mosque also preaches (maw’idhah) before the Friday sermon (khutbah), his sermons are shorter than those at the Preston Mosque. It is also worth noting that the imam at the Preston Mosque delivers his sermons extemporaneously, whereas the imam in the Broadmeadows Mosque 13 generally follows written text. Furthermore, both men and women attend the Friday 14 prayers at the Preston Mosque, while only men attend the Broadmeadows Mosque. Other less important differences also exist, but they will not be discussed here, as they do not relate directly to the subject matter of this paper. 3.2. Classification of Sermons Since I did not record the full text of each sermon, I base my analysis primarily on my personal observations. In particular, I have focused on the use of key words and concepts. Although I did note down some key words, significant anecdotes, main topics and themes in my notebook, my analysis does not fulfil the requirement of full content analysis or data analysis management. Rather, my goal is to give some idea of the use to which imams at There is a distinction between preaching (maw’idhah or wa’adh) and sermons (khutbahs). Preaching is held before the Friday prayer and sermon (khutbah), and is not compulsory. However, sermons (khutbahs) are an essential part of Friday prayer. We observe that preaching is sometimes delivered by imams, while other religious leaders in the community do so at other times. 12 Although some scholarly literature on the Islamic history of sermons (khutbas), homily (preaching and advice), and the philosophy of preaching is available in English, it is quite limited compared to the extent of the literature in the Turkish and Arabic languages. It has been noted that poems, proverbs and anecdotes are important elements of the Friday sermons. Being raised with an exposure not only to knowledge, but also to the culture and literature, gives overseas-trained imams an advantage in relating and articulating issues in Friday sermons from religious, cultural and literary aspects. 13 The Turkish imam does not follow a written text in his preaching before the Friday sermon, but he does follow a text in the sermons (khutbah). 14 In almost every mosque in Australia, women participate in prayer more during the month of Ramadan, but their numbers are significantly lower during normal Friday prayers. It is not compulsory for women to attend the mosque on Fridays, whereas it is compulsory for men. 11 32 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons two important mosques in Melbourne put the opportunity of the Friday sermons to increase the general and religious knowledge and religiosity-spirituality of their congregations. To achieve this goal, we will first consider the sermon topics from three perspectives. As the content of a sermon has an effect on the religious inclination and formation of the people, it is essential to see how the selected topics address the belief/faith (thought), actions (behaviour and worship), and emotions (spirituality) of Muslims. In this analysis, we follow the format developed and applied by Dr. Ahmet Onay in his examination of Turkish sermons. Onay prepared his work under the auspices of the 15 Supreme Board of Religious Affairs for the Presidency of the Turkish Republic. Before the analysis, however, I provide a list of sermon subjects in the following tables: Broadmeadows Mosque (Majority Muslims of Turkish descent) Week Imams Subjects 1 Imam A Self questioning and re-evaluating the past year 2 Imam A Sincerity and intention 3 Imam A Truthfulness and integrity 4 Imam A The notion of piety, taqwa 5 Imam A Love for the family of the Prophet (ahl al-bayt) 6 Imam A The people of paradise and hell 7 Imam A The noble birth of the Prophet Dangerous habits and precautions/the Green Crescent (Turkish 8 Imam A Temperance Society) 9 Imam A The rights of women in Islam (Women’s Day) 10 Imam A The acceptance of the Turkish National Anthem. 11 Imam B Generosity 12 Imam A Preventing the action of telling lies 13 Imam A Prophetic examples 14 Imam A 23 April Festival of Children 15 Imam A The importance of endowment in Islam (Week of endowment) 16 Imam A The danger of backbiting 17 Imam A The importance of youth in Islam 18 Imam A Bushfires and the importance of helping one another 19 Imam A The danger of envy, jealousy and holding grudges 20 Imam A The importance of ritual prayer in Islam 21 Imam A The notion of immigration in Islam (hijrah) 22 Imam A Celebration of the heavenly journey of the Prophet (mi’raj) 23 Imam A Importance of Ramadan and fasting 24 Imam B Qur’an and its place in Islam Celebration of 30th of August (The Festival of Victory) – Turkish 25 Imam A National Holiday 26 Imam A Celebration of the night of power (laylat al-qadr) 27 Imam A The notion of brotherhood and love 28 Imam A Relationship between relatives and its importance 29 Imam A The notion of repentance 30 Imam A The importance of family 31 Imam A The notions of praise (hamd) and thanksgiving (shukr) 32 Imam A The rights of neighbours 33 Imam A The Festival of Sacrifice – Eid-ul Adha 15 Ahmet Onay, Diyanet Hutbelerinin İçerik Analizi. İslami Araştırmalar Dergisi, Vol, 17, 2004, 1-13. 33 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Imam A Albayrak / Friday Sermons The notion of knowledge and how it is valued by Islam The spiritual disease of two-facedness and hypocrisy Covering up the mistakes of others The duties of spouses towards each other The day of Ashura (Noah’s pudding) 16 Codes of ethics Spiritual balance between fear and hope Commanding good and forbidding bad The importance of mosques and their functions Preston Mosque (Majority Muslims of Arab descent) Week Imams Subjects 1 Imam A 17 Backbiting, mocking and slander Worldliness and love of fortune. 2 Imam A Sub-subject: summer Qur’an courses for children The importance of immigration (hijrah). 3 Imam A Sub-subject: Israel’s attack on Gaza is mentioned. 4 Imam A The place of women in Islam 5 Imam A The notion of ego and whim Bushfire in Victoria (and in Australia) and the importance of 6 Imam A helping those affected by this calamity 7 Imam B The meaning of Islam (from a religious context) 8 Imam B The meaning of belief in One God (Allah) The notion of material and spiritual ihsan (doing goodness as if 9 Imam A you are constantly in the presence of God) 10 Imam B The upbringing of children (specifically boys) 11 Imam B Good manners and modesty 12 Imam B Why families and societies are unhappy today 13 Imam A The notion of thanks and why we see unthankful people 14 Imam B Patience and the Prophet as an example 15 Imam B Islam: Togetherness in theory and practice 16 Imam B Competing in performing good deeds 17 Imam B The compassion of God and the Prophet/Universality of Islam 18 Imam B The notion of repentance in Islam 19 Imam B Fasting in Ramadan Islam: Togetherness in theory and practice (obedience to God 20 Imam C and the Prophet) Imam D Importance of worship: fasting, ritual prayer, almsgiving and 21 (Overseas other moral values Guest) Imam D 22 (Overseas Ramadan, almsgiving and the notion of paradise and hell Guest) Acceptance of the call to God and the Prophet: Unity and the 23 Imam B continuation of good habits after Ramadan Importance of ritual prayer (salat) and prayer with a 24 Imam B congregation 16 It is important to note that celebration of this day has quite a different meaning and significance for Shi’ite Muslims. 17 Imam A from Preston mosque is not the same imam from Broadmeadows. 34 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) 25 26 Imam B Imam B 28 29 30 31 32 Imam E Imam B Imam B Imam B Imam B 27 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Imam B Imam B Imam F Imam B Imam B Imam B Imam A Imam B Imam B Imam B Imam B Imam B Imam B Albayrak / Friday Sermons Muslim sources for religious questions and query Meaning of Islam and being a Muslim Lawful and unlawful matters in Islam/ The relationship between the Creator and creatures Love of this world, the reality of death and the hereafter Pilgrimage and the importance of sacrifice Pilgrimage and patience. The notion of the Unity of God Festive days and the unity of Muslims The minor signs of the Day of Judgement – I The minor signs of the Day of Judgement (the lawful and unlawful in Islam) – II The importance of immigration (hijrah) in the history of Islam The minor signs of the Day of Judgement – III The minor signs of the day of Judgement – IV Introduction to the major sign of the Day of Judgement Patience and the various types of patience Major signs of the Day of Judgement Moral diseases: Lies, dissemblance and hypocrisy Meaning of the celebration of the birth of the Prophet Moral diseases: Tattling, slander and joking excessively Moral issues: Being trustworthy Moral issues: The rights of a mother and father At both mosques, the sermons of the imams — some of whom have memorized the entire Qur’an — covered topics that emphasised ethical and moral matters. There was a stress on being a good Muslim and a positive member of society, exercising one’s social obligations toward one’s neighbour, and fulfilling one’s religious duty towards God. Even when different imams covered the same topic, the most common subject matter related to the connection between faith and practice. In fact, during my one year at the Preston Mosque, Shaykh Fahmi al-Imam, who offered Friday prayer sermons twice, covered the topic of faith and practice in his first sermon. In his second sermon, like the advice Jacob offered to his sons in the Qur’an, he, with the wisdom of experience, covered the topic of ‘how migrant Muslim Australians can contribute to their new country and community’. Appropriately, he did this on the anniversary of the migration of the Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina. It is important to note that no imam at either mosque dealt with controversial topics during this period, specifically those relating to political issues. Even though a member of the al-Shabab group claimed to the newspapers that their plan to attack Holsworthy army barracks was discussed at the Preston Mosque, 18 I can confidently say that during my two and half years of observation at both the Preston and Broadmeadows Mosques, no such matters were ever discussed. More importantly, during the sensitive period of Israel’s attack on Gaza, the Broadmeadows Mosque only referred to the issue indirectly, without mentioning any names, while the Preston Mosque criticized the military action and 18 A reporter from the Herald Sun claimed, ‘The terror plotters all prayed at the Preston Mosque and it was through that association that the conspiracy developed over a number of months.’ (See the article: http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/three-melbourne-men-guilty-of-planning-terror-attack-on-nsw-armybase/story-e6frf7kx-1225975357525.) Another reporter expressed concerns about the influence of preaching on youth. See the article in The Age (June 13, 2010), ‘Radical preacher grooming young for terror’. 35 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons atrocity in a restrained manner. Similarly, when the President of the Board of Imams addressed the recent issue of a US pastor’s intention to burn the Qur’an, he spoke with great constraint, stating that the best response of Muslims to such behaviour was to read the Qur’an more frequently and apply its moral and ethical teachings. In my opinion, this was wise advice, as it left no room for any negative reaction to the unfortunate news. While important events may sometimes shape the topic of the sermon, preachers generally follow a pre-arranged program. Neither mosque utilizes modern technology. Sermons deal especially with issues faced by Australian Muslims. However, this does not mean that issues relating to the wider community are avoided. One important example was the occasion of the catastrophic bushfires in Victoria in 2009. During this period, the Imams in both mosques kept the congregation informed of the details of the fires, encouraged members to assist and support those affected by the fires, and explained that this was a religious duty and that the mosques should play an important role in organising groups to collect money and send aid to the fire-affected areas. Muslims united with the wider community and became part of one body to support those in need. Muslims did not simply leave the imam’s advice behind in the compound of the mosque, as it were, but acted on the advice in a practical manner. Prayers for rain were also held at both mosques, along with expressions of condolence and sympathy for the victims of the fires. This solidarity of Muslim communities with their fellow Victorians of all religious backgrounds 19 during a time of disaster was a strong example of unity within diversity. One significant difference between the sermons at the two mosques is that the Turkish-dominated Broadmeadows Mosque tended to emphasise Turkish national holidays, whereas the Imam at the majority-Arab congregation at the Preston Mosque tended to stress the need to raise funds for hospitals and orphanages in Middle Eastern areas that had experienced calamities. 3.3. Content of the Sermons The lists above indicate the general content of the sermons, but if we take a closer look from the perspective of Onay’s threefold classification, we can make more specific comments. The table below shows the content of the sermons within the framework of Ahmet Onay’s classification, which distinguished Belief/Thought, Actions/Practice and 20 Emotion/Spirituality. Broadmeadows Mosque: Belief/Thought The Prophet Celebration of the heavenly journey of the Prophet (mi’raj) Qur’an and its place in Islam The celebration of the night of power (laylat al-qadr) The notion of knowledge and how it is valued The notion of immigration in Islam (hijrah) Actions/Practice Dangerous habits and precautions/ Green Crescent (Turkish Temperance Society) 19 I observed a similar response at both mosques during the recent catastrophic floods in Queensland. We accept that this classification has some shortcomings, but for the sake of simplicity we consider this level of generalisation unavoidable. 20 36 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons The rights of women in Islam (Women Day) Generosity Prevention of telling lies Prophetic example Social solidarity and the importance of endowment/waqf Backbiting Importance of youth Bushfires and the importance of helping one another The danger of envy, jealousy and holding grudges Importance of ritual prayer The importance of Ramadan and fasting Relationship between relatives and its importance The importance of family The rights of neighbours Celebration of 30th of August (Victory festival) The festival of sacrifice Covering up the mistakes of others The duties of spouses towards each other The day of Ashura (Noah’s pudding) Commanding good and forbidding evil The importance of the mosque and its function Emotion/Spirituality Sincerity (ikhlas) The notion of truthfulness (sidq) The notion of piety (taqwa) Love of the family of the Prophet Muhammad Paradise and Hell The notion of brotherhood and the notion of love The notion of repentance The notion of praise (hamd) and thanksgiving (shukr) in Islam Spiritual balance between fear and hope The spiritual disease of two-facedness and hypocrisy Codes of ethics Preston Mosque: Belief/Thought Meaning of Islam Meaning of belief in One God (Allah) Islam: Togetherness in theory and practice Compassion of God and the Prophet/Universality of Islam Islam: Togetherness in theory and practice (obedience to God and the Prophet) Acceptance of the call to God and the Prophet: Togetherness in theory and practice in Islam The meaning of Islam and being a Muslim The meaning of the celebration of the birth of the Prophet Muslim sources for religious questions and query The lawful and unlawful in Islam/halal and haram Actions/Practice Back biting, mocking and slander The importance of immigration The place of woman in Islam 37 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons Bushfires in Victoria/Australia and helping those who are affected by calamity Upbringing of children Good manners and modesty Patience and examples from the patience of the Prophet Competing in performing good deeds Fasting in Ramadan Importance of worship: fasting, ritual prayer, almsgiving and other moral values Ramadan, almsgiving, the notion of paradise and hell Importance of ritual prayer (salat) and prayer with a congregation Pilgrimage and the importance of sacrifice Festive days and the unity of Muslims The importance of immigration (hijrah) in the history of Islam Patience and the various types of patience Moral diseases: Telling lies, dissemblance and hypocrisy Moral diseases: Tattling, slander and joking excessively Moral issues: Being trustworthy Moral issues: The rights of a mother and father Spirituality/Emotion Worldliness and the love of fortune The notion of ego and whim The notion of material and spiritual ihsan Happiness The notion of thanks in Islam The notion of repentance in Islam The love of world, the reality of death and the hereafter Minor signs of the Day of Judgement Minor signs of the Day of Judgement Minor signs of the Day of Judgement Introduction to the major sign of the Day of Judgement Major signs of the Day of Judgement The two lists above differ from the earlier list of sermon topics. Although imams shift from one issue to another from time to time during their sermons, they generally tend to focus on their pre-arranged subject. Actually, this kind of shift is more common in text-free sermons than in the text-dependent discourses at the Broadmeadows Mosque. At first glance, it is interesting to note that the imams’ major concerns are related to the practical and emotional sides of religion, rather than its dogma. At the Broadmeadows Mosque, sermons about the dogma (beliefs) constituted 16% of all sermons (that is, seven sermons), while they constituted 18% of sermons at the Preston Mosque, though the fundamentals of Islam did come to the fore as a side issue from time to time. This ratio indicates that there is not a strong correlation between the three dimensions. Similar to 21 the outcomes of Onay’s analysis of sermons in Turkey, it is worth noting that two articles of faith (I bear witness that there is no God but Allah, and I bear witness that Muhammad is His messenger) were not discussed at all at the Broadmeadows Mosque, while they were discussed in detail at the Preston Mosque. In addition, two other fundamental principles of Islam — belief in Angels and destiny — were not discussed at either mosque. A belief in the hereafter (which is a spiritual dimension, according to Onay’s analysis) emerged in connection with the reality of death, paradise/hell and the signs of the Day of 21 Ahmet Onay, “Diyanet Hutbelerinin İçerik Analizi”, İslami Araştırmalar Dergisi, Vol.17, 2004, 1-13, at 6. 38 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons Judgement. This dimension (issues related to the hereafter) constituted 21% of sermons (9) at the Broadmeadows Mosque and 27% (12) at the Preston Mosque. The major focus of both mosques was on the practical dimension of religion. This area constituted 63% of sermons at the Broadmeadows Mosque and 55% at the Preston Mosque. Obviously, the majority of these sermons dealt with principles of Islam, such as ritual prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, almsgiving, and so on. Nevertheless, there were also many other topics that pertained mainly to ethical and moral issues. Another interesting topic which was dealt with from time to time was materialism. The imams frequently pointed out that an increase of material wealth may improve one’s physical and social wellbeing but can prove to be a trap, as one may start to pay more attention to worldly power and possessions than to the spiritual dimension of life. The strong emphasis they placed on materialism would seem to suggest that these sorts of problems existed within their congregations. If we scrutinise the two lists closely, we will see that there is a greater variety of sermon topics at the Broadmeadows Mosque than at the Preston Mosque. The reason for this, I think, is probably that more than one imam delivered the sermon at the Preston Mosque and they sometimes duplicated topics. In addition, some modern practical issues were not discussed clearly during sermons at either mosque — issues such as mortgages, interest-free banking systems, insurance and certain medical ethical matters were omitted. At this stage it is also important to note that at the Preston Mosque, imams frequently discussed the lack of an individual body of fatwa (legal reasoning). This internal problem would seem to stem from the ethnic and cultural diversity of the Muslims attending the Preston Mosque. However, I did not come across this issue being raised by the imams at the Broadmeadows Mosque. Importantly, imams also preferred to make general remarks, rather than tackle specific arguments. As was mentioned above, it was quite rare for imams to use contemporary examples to illustrate their points; they preferred to cite examples from the past. There was also strong emphasis on the family, marriage, issues relating to women and men in general, Muslim youth and children. At the Broadmeadows Mosque, the imam delivered his sermon from a written script prepared by a religious committee (consisting of imams and the Turkish Attaché). In fact, other imams from Turkey who work in Melbourne deliver the same khutba prepared by the same committee. The election of sermons delivered by the imams at the two mosques in Melbourne (regardless of whether they are raised in Australia or come from overseas) indicates that they are extremely reluctant to bring overseas problems to their respective mosques. This is an important point in relation to the question raised at the beginning of this paper about the training of imams in Australia. As was indicated in the tables provided above, the content of the sermons at the two mosques was comprehensive, and the imams were well qualified to convey their message. They employed various rhetorical devices to communicate with their congregations, such as using intonation in a very efficient way, raising many rhetorical questions (which are not expected to be answered by the congregation, but evoke an emotional response), quoting poems or very interesting anecdotes in relation to the topic discussed in the sermons, and a balanced use of irony and humour. 39 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons 4. TRAINING IMAMS IN AUSTRALIA? At the outset, we need to ask whether any existing Australian institution can educate and produce imams satisfactorily. It is true that well-respected scholars teach Islamic Studies at a number of Australian universities, but none of the courses are designed or developed for training imams. As far as I can see, no existing programs are suitable for educating imams. It is hard to imagine that any one institution training imams could cater for the religious and cultural needs of all Muslims in Australia. It is also hard to imagine any one structure or establishment that would appeal to all Muslims. Just as ministers from different Christian denominations are trained at different institutions, so imams from different backgrounds have different training requirements. There is no central body among Muslims, and common training is simply out of the question. However, this does not mean that it would be impossible to bring different Muslim groups together to find some kind of general theological consensus. I believe it makes sense to expect tertiary level institutions to support imams, and also to create a space for the education of young Muslim women and of women community leaders. I am also convinced that the establishment of an advisory body via the collaboration of organisations such as the Board of Imams, the Islamic Council of Victoria and similar organisations, as well as various Islamic school teachers and trainers, could offer workshops and short but concentrated programs or courses for inculturating overseas imams. Topics could include Australian values, Australian life, and other topics that should be addressed during sermons but are not normally paid much attention. Within this framework, imams could be educated on topics such as multiculturalism, integration, inter-faith dialogue, and common moral and ethical issues (such as medical ethics, environmental issues, and social and inner peace); as well as, most importantly, the way in which Muslims, as a dynamic faith group, can contribute to the wider community, and be frontrunners in encouraging dialogue and communication amongst the populace. Thus, the need is to create a program which can help imams to learn more about their new society, so that they can in turn give better advice to their immediate communities. Since there is no single tertiary level institution for the training of imams, this would seem the best approach at present. Otherwise, initiating the training of imams in existing institutions would not mean that different Muslim communities would accept these imams without hesitation. Nonetheless, it is safe to assume that with the passage of time, especially with the engagement of more Australian-born Muslims (third and fourth generation Muslims) in community and religious affairs, more serious Australian Muslim 22 institutions for the training and formation of imams will gradually develop. Clearly, changing the current situation will require both time and effort. Another question which should be asked at this juncture is who will appoint these imams and which mosque each will be appointed to. As I understand it, the majority of imams are sponsored by mosque committees, in other words, by the community. This structure requires a sensitive balance between the imam and the community, and is quite different from state-sponsored service areas. 22 The structure of the family, changes to the family structure and the generation gap are important issues which need to be taken seriously by every community. 40 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons On the other hand, there is apparent disadvantage in insisting on imams being trained in Australia. In our rapidly globalising world, Muslim countries might require future religious leaders of their own non-Muslim minorities to be trained in statesponsored institutions in their own country, on the basis of reciprocity. I think that such a practice or rule would upset sincere believers in almost every country. Politicians should be very careful not to fall into the trap of political pragmatism or populism for the sake of any temporary benefit. They would be well advised to abstain from taking stances that impose, command, or prohibit certain religious and cultural behaviours. Instead, they would do well to exert the utmost effort to admit these existing problems and try to fill the gaps and remove the deficiencies in the existing system. The imposition of top-down projects without consultation will do more harm than good to the religious affairs of the communities they seek to serve. 5. CONCLUSION Muslims are a relatively ‘new’ migrant community in Australia, especially when compared with settlers like the Irish, Chinese and Italians. Nonetheless, owing to the media and many other factors, the presence of Muslims sometimes provokes tensions and raises questions. Furthermore, the growing number of Muslims in the West seems to cause demographic anxiety and clash-of-civilization theories among some non-Muslims. From the perspective of Muslims, the host country is their new home, and the home of their children and their children’s children. Although various global developments create immigrants and religious Diaspora, Muslims seem to attract more than their fair share of attention. In their adopted homeland, mosques serve a unique purpose, enabling recent arrivals to meet like-minded Muslims. The training of imams and the content of the Friday sermons are thus very important matters. As was shown above, sermons are 23 quietly received by thousands of people each week. Although very good Islamic Studies departments exist in Australian universities, this article tries to show that there is no specific institution for educating imams in Australia. According to my two-and-a-half-year experience and observation, the current imams in the two mosques are well qualified and quite capable of serving their respective communities. The content of the services is a clear reflection of the vast knowledge and experience of imams in Islamic studies. In addition, their sermons indicate that they are keener to preach about ethical and moral issues than about political matters, and that they do not wish to import overseas problems into Australia. In the short term, instead of focusing on the unrealistic goal of training our own imams in Australia (though this may be possible at some future date), current departments of Islamic Studies, together with various NGOs, should organise regular workshops and courses to facilitate the integration 24 and adaptation of new imams from overseas. It is also important to note that the 23 Bearing in mind the number of mosques in Australia, and in Victoria in particular, the two mosques I visited are simply representative of the whole. They have attendances that approximate the attendances at other Australian mosques. (See the list of all mosques and musallas (small mosques) in Australia: http://www.islamiaonline.com/masjidfinder/#.) 24 I believe that Prof. Abdullah Saeed from Melbourne University, Attaché Huseyin Koc from the Melbourne General Consulate of the Republic of Turkey, and representatives of the Board of Imams in Victoria currently conduct workshops and training programs for imams in Victoria. This is an important initiative that will contribute greatly to the continuing education and training of imams in Australia. 41 AEJT 19.1 (April 2012) Albayrak / Friday Sermons pluralistic and general nature of these courses should allow imams from different social and ethnic backgrounds to participate actively in them. In addition, these programs should be designed to emphasise the multicultural nature of Australian society. The challenge facing imams is a fundamental one: how can they help their congregations to sustain their Muslim identity without opposing either modernity or the multicultural fabric of their new homeland? Author: Ismail Albayrak is the Fethullah Gulen Chair in the Study of Islam and MuslimCatholic Relations, in the Faculty of Theology and Philosophy at Australian Catholic University. He received his PhD degree from Leeds University in 2000. His areas of special interest are Qur’anic Studies, Classical exegesis, Contemporary Approaches to the Qur’an, Western Scholarship of Islam, and Orientalism. Email: Ismail.albayrak@acu.edu.au 42