ANTITRUST LAW: Dominant Firm Conduct

Janet L. McDavid and Erica S. Mintzer

December 17, 2007

Buy one, get one free! Membership rewards! Deep discounts! These phrases are music to

consumers' ears. Buyers are very familiar with, and attracted to, these offers, which are

common strategies that businesses use to drive demand and increase sales vis-à-vis their

competitors. This is the very essence of competition.

Yet, when these strategies are undertaken by a firm with market power, they may run afoul

of the antitrust laws. Some dominant-firm conduct is easily condemned, but much singlefirm conduct falls into grey areas, and there are few bright-line rules on what conduct goes

"too far" so that liability will attach. This could make firms with a strong market position

hesitant to compete aggressively for fear of crossing the line.

Competition authorities and courts have struggled to find a framework to distinguish anticompetitive conduct from benign or effective competition. The challenge is crafting a test

that does not create too many "false positives," which would chill aggressive competition, or

too many "false negatives," which would let anti-competitive conduct go unchallenged. In

some areas, dominant firms can find guidance to enable them to manage their business

effectively. However, tests have not been delineated for all business strategies, and firms

are left with uncertainty. Also, some tests differ among states or countries. What's a

monopolist to do?

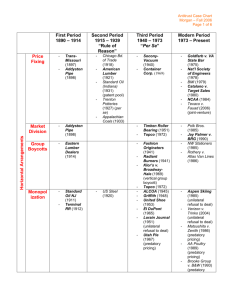

Single-firm conduct is a major focus of enforcement

The antitrust laws protect competition by prohibiting conduct that impairs the proper

functioning of markets. A significant part of antitrust enforcement focuses on single-firm

conduct. Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits both actual and attempted monopolization,

making it illegal to "monopolize, or attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or

commerce." Despite its literal language, § 2 does not prohibit the mere possession of

monopoly power, but rather the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power ("as

distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business

acumen, or historic accident"). U.S. v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 50 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

It is widely recognized that the potential to succeed provides significant incentives to

innovate and invest in devising a "better mousetrap" and "is an important element of the

free market system . . . induc[ing] risk taking that produces innovation and economic

growth." Verizon Comm. Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko LLP, 540 U.S. 398, 407

(2004). Thus, the law proscribes only conduct that improperly maintains or facilitates the

acquisition of a monopoly. That is, liability under § 2 requires exclusionary conduct, a term

that has proved difficult to define. The U.S. Supreme Court has described it as conduct that

not only tends to impair opportunities of rivals, but also "does not further competition on

the merits or does so in an unnecessarily restrictive way." Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen

Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585 (1985). More than 100 years after passage of the

Sherman Act, precise standards are rare and the law remains uncertain.

There is a specific standard for some single-firm conduct. The cost-based test for predatory

pricing adopted in Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993),

is an example. Predatory pricing requires pricing below "an appropriate measure of cost,"

and a prospect of recoupment. Implicit in this test is the priority that U.S. antitrust laws put

on protecting consumers, not competitors. Some have suggested fashioning a cost-based

test for all exclusionary conduct, but there is no established standard for most potential

monopoly violations, such as loyalty discounts, technological or product bundling and

refusals to deal.

Complicating matters is that conflicting tests exist, such as for bundled discounts — i.e.,

offering a discount for two or more products purchased together. In LePage's v. 3M, 324

F.3d 131 (3d Cir. 2003), the 3d U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a jury verdict that 3M's

bundled pricing violated § 2. A competitor sued 3M, which had a monopoly in transparent

tape, for conditioning discounts on purchases of other products. The court rejected the

argument that bundling could not be anti-competitive if the price was above-cost because a

bundle "offered by a monopolist . . . may foreclose portions of the market to a potential

competitor who does not manufacture an equally diverse group of products and who

therefore cannot make a comparable offer."

In contrast, recently the 9th Circuit, in PeaceHealth, No. 05-35627 (9th Cir. Sept. 4, 2007),

criticized the LePage's test and adopted a cost-based test: "[T]he primary anticompetitive

danger posed by a multi-product bundled discount is that [it] can exclude a rival who is

equally efficient . . . simply because the rival does not sell as many products. [A]

plaintiff . . . must prove that, when the full amount of the discounts given by the defendant

is allocated to the competitive product[s], the resulting price of the competitive product[s]

is below the defendant's incremental cost to produce them." This test enables sellers to

evaluate multiproduct pricing policies. Given the split between the 9th and 3d circuits,

perhaps the high court will resolve the dispute and set a standard for bundled discounts.

In the meantime, the U.S. antitrust agencies have held hearings on single-firm conduct (and

plan to issue a report), and the Antitrust Modernization Commission considered dominantfirm standards. Several tests have been proposed to determine whether conduct is

"exclusionary":

• The "no economic sense" and "profit sacrifice" tests define conduct as exclusionary if it

only makes sense because of its ability to eliminate competition, or if the dominant firm

sacrificed short-term profits. It provides a clearer standard, but is narrow, and even minimal

efficiencies can save a monopolist, despite harm that outweighs the efficiencies.

• The "less efficient rival" test classifies conduct as exclusionary only if it would eliminate an

equally or more efficient rival. It will not protect inefficient rivals at consumers' expense, but

it may be too narrow when the monopolist is able to keep competitors from becoming

efficient, and it may be administratively difficult when applied to certain conduct.

• The "consumer welfare" test, which was applied by the D.C. Circuit in its Microsoft

decision, balances efficiency or other benefits of conduct against anti-competitive effects —

much as the rule of reason does under § 1 of the Sherman Act. It focuses on the goal of

antitrust — enhancing consumer welfare — but has been criticized as being difficult to

administer.

Many contend that a "one size fits all" test is an impossible goal, given the diversity of

conduct. For example, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has focused on what it calls

"cheap" exclusion, such as fraud and deception, which costs or risks little to the firm

engaging in it (unlike predatory pricing, which is "expensive"), and does not involve any

efficiencies. A cost-based test would not capture this conduct. The FTC used this standard

when it unanimously held that Rambus Inc. engaged in unlawful monopolization by actively

concealing and withholding information about its intellectual property that was material to a

standard-setting process. In the Matter of Rambus Inc., No. 9302 (July 31, 2006). The FTC

relied on a duty of good faith and a deception-based standard — a relatively novel approach.

International angle adds to the complications

The fact that firms compete internationally adds more complications. Even the United States

and the European Union have significant differences, for example, in the treatment of

loyalty rebates. In the European Union, dominant firms are essentially prohibited from

offering them, while the United States uses a case-by-case analysis to determine the extent

of foreclosure and consumer harm.

While the Justice Department has brought no recent § 2 cases, the European Commission

(E.C.) has actively pursued cases against dominant firms — most notably Microsoft. In 2004,

the E.C. ruled that it had abused its dominant position by bundling its Media Player with its

operating system and by refusing to share technical information that would enable PCs to

communicate with competitors' servers. This past September, the European Court of First

Instance upheld that decision. Thomas Barnett, assistant attorney general for the Antitrust

Division, took the rare step of issuing a press release criticizing this ruling because it "may

have the unfortunate consequence of harming consumers by chilling innovation and

discouraging competition."

In July, the E.C. asserted that Intel Corp. acted "with the aim of excluding its main rival" by

offering customers substantial rebates in exchange for exclusivity; making payments to

induce customers not to use competing chips; and making predatory bids. The FTC is

reported to have refused to open an investigation of Intel. The E.C. also has proceedings

against Rambus and Qualcomm Inc., based on alleged abuses of the standard-setting

process.

As the Antitrust Modernization Commission noted, "Section 2 standards should be clear and

predictable in application and administrable." That has not yet been achieved. Agencies,

courts and commentators are debating various standards as they try to enable aggressive

competition on the merits, deter exclusionary conduct and provide more certainty so firms

can plan their business strategies. As then-Judge Stephen G. Breyer wrote in Town of

Concord v. Boston Edison Co., 915 F.2d 17, 22 (1st Cir. 1990), antitrust rules "must be

clear enough for lawyers to explain them to clients," and "administratively workable."

Janet L. McDavid is a partner, and Erica S. Mintzer is counsel, at Hogan & Hartson in

Washington.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE DECEMBER 17, 2007 EDITION OF

THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL © 2007 ALM PROPERTIES, INC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. FURTHER DUPLICATION WITHOUT PERMISSION IS PROHIBITED.