The symbolism of querns and millstones

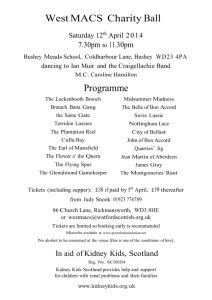

advertisement

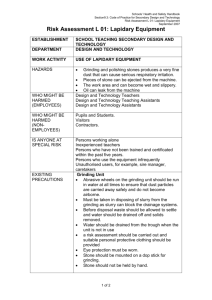

The symbolism of querns and millstones SUSAN WATTS Watts, S. 2014. The symbolism of querns and millstones. AmS-Skrifter 24, 51–64, Stavanger. ISSN 0800-0816, ISBN 978-82-7760-158-8 From saddle querns to rotary querns to millstones powered firstly by human and animal power and later by water and wind, querns and millstones are one of our oldest and longest used craft tools. They have been used for grinding many different materials but are synonymous with grinding grain. From the earliest cultivation of cereals in the Near East some 12,000 years ago through to the advent of roller milling in the 19th century, querns and millstones were thus of vital importance at a daily subsistence level and in consequence familiar to everyone, as indeed they still are in some parts of the world. As such everyday tools they have been wellplaced as a medium through which to explain some of life’s mysteries, from the turning of the seasons to why the sea is salt. The symbolic and metaphoric meanings of querns and millstones can be shown to be linked not only to what they ground, who used them and how they operated but also to their transforming properties, turning a raw material into a refined, usable product, and even potentially to their size and colour. Bringing together mythology, legend and literature with history, archaeology and living tradition, this paper explores the symbolism and meaning of querns and millstones from the prehistoric period through to the present day. Susan Watts, Devon County Coucil, County Hall, Topsham Road, Exeter, Devon EX2 4QW, England. Phone: (+44) 01392382994. E-mail: susan.watts@devon.gov.uk Keywords: quern, millstone, symbolism, transformation Introduction A symbol may be defined as “something that stands for, represents, or denotes something else” (OED Online 2012). This may be due to its analogous or similar qualities to that which it represents or by association, be that in fact or in thought. Querns and millstones can be used for grinding many different materials but, first and foremost, they are instruments for grinding grain. As such they are intimately associated with the daily provision of food. As Robert Jamieson’s poem states, “The music for a hungry wame [stomach]/Is grindin’ o’ the quernie” (Colville 1892:126). Thomson, travelling in the Near East in the 19th century, commented on the “hum of the hand-mill” which he expected to hear every morning and evening in Arab villages and camps. The sound, he said, “is suggestive of hot bread and a warm welcome when hungry and weary” (Thomson 1985:526 [1877]). In this respect it is easy to understand why, in the Bible, the laws of Moses state that one should not take an upper millstone as a pledge, for that is taking a man’s life away, and why the absence of the sound of millstones is used as a sign of desolation, symbolic of a 53 place that is uninhabited and forsaken (Deuteronomy 24.6, Jeremiah 25.10, Revelation 18.22 (Authorised King James Version)). Yet the task of milling is also used in the Bible as a symbol of toil, drudgery and slavery. Isaiah, predicting the fall of Babylon says, “Come down, and sit in the dust, O virgin daughter of Babylon, sit on the ground: there is no throne…Take the millstones, and grind meal…” (Isaiah 47.1–2). Symbolic meanings are not fixed, however, but dependent upon particular social, ideological and contextual circumstances and subject to spatial and temporal change and adaptation. In addition, as Gerrard (2003) states, “the symbolic meanings of object[s] can change according to the context in which [they are] found”, embodying, for example, a specific person, place, task or event. They may also be peculiar to particular communities and impossible to understand by those who do not have the same world view (Tilley 1999:9). The symbolism appropriated to milling stones is no exception. Throughout the 12,000 years or so of their history, from the earliest saddle querns and the beginnings of agriculture in the Neolithic Near Susan Watts East, through the introduction of the rotary quern in the Iron Age to millstones turned firstly by human and animal power and subsequently by water and wind, querns and millstones have been important to people at a daily subsistence level. As Crawford states, they are “an excellent instance of necessary things for they grind the corn which for an agricultural people is the chief basis of life” (Crawford 1953:98–99). It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that such “necessary” and consequently familiar “things” have been used as a means to explain various natural and human phenomena such as why the sea is salt, the turning of the seasons and the place of men and women in the world. This paper explores some of the symbolic and metaphoric meanings that have been appropriated to querns and millstones by virtue of their physical properties, the act and motion of grinding, their association with women and with grain and the harvest. It begins, however, with a brief outline of previous research on the subject. It is based on a paper given at the Millstone Colloquium in Bergen, Norway in 2011 and also taken in part from the author’s PhD thesis on the structured deposition of querns in the south-west of England (Watts 2012). Previous work on the symbolism of querns and millstones The study of querns and millstones as a “distinctive historical interest” (Bennett & Elton 1898:vii), really only began in the late 19th century, at a time when the roller milling industry was expanding rapidly in the western world, leading to the demise of the traditional country corn mill. Early articles and publications by Barnwell (1881), Bennett & Elton (1898–1904) and Kozmin (1917), for example, focused on the history and development of milling, incorporating ethnographic observations together with classical and biblical quotations. Typological development remained a key theme throughout the 20th century with publications by authors such as Curwen (1937), Storck & Teague (1952), Moritz (1958), Bucur (1979–1983) and Carelli & Kresten (1997). The 20th century also saw a growing interest in quarries and production, an interest which intensified in the 1980s with, for example, articles by Hayden (1987), Peacock (1987), Williams-Thorpe (1988) and Wright (1988). These topics continue to be an important aspect of quern research today. Typological, historical and ethnographic studies have also been enjoying something of a renaissance over the past decade, helped in no small part by a flurry of 54 international conferences which have greatly stimulated interest in both querns and millstones. Recent publications include Adams (2002), Procopiou & Treuil (2002), Watts (2002), Barboff et al. (2003), Frankel (2003), Shaffrey (2006), Hamon & Graefe (2008), Heslop (2008), Williams & Peacock (2011) and Hamon & Gall (2013) to name but a few. By comparison, the symbolism of querns and millstones has been a relatively little researched subject and generally separate from other strands of quern and millstone study. Nevertheless, it is a wide-ranging theme and consequently most authors have tended to focus on a specific aspect of that symbolism or on a particular type of mill or period. Earlier articles such as Rydberg’s section on The Great World-Mill (Rydberg 1887:79–83) and Johnston (1908–1909) show that the mill in Scandinavian and Teutonic mythologies in particular has long been a fascinating subject. It is also one that continues to intrigue. References to such tales are included, for example, in Santillana & Dechend (1969). They discuss the evolution of an ancient belief in the cyclical nature of the world based on the procession of the polestar and the circle of the heavens which is likened to the turning of a millstone. Santillana and Dechend’s arguments and conclusions have been widely criticised but the book nevertheless contains much detail that can be further investigated. Tolley (1994–1997) compares the meaning and origins of two tales, the Sampo and Grottasöngr, noting that whereas the Sampo only produces good things in the form of wealth, meal and salt, the Grotti can grind ill as well as good fortune. As with other aspects of quern studies, articles relating to the symbolism of querns and millstones have increased over the last decade, including Worthen (2006) who looks at mills, particularly windmills, as represented in medieval art and literature and Ambrose (2006), who explores the meaning of the mystic or Eucharistic mill carved on one of the capitals at Vézelay Abbey, Burgundy, France. Scandinavian mythology also remains popular, with online articles such as Jesch (2010) and Stone (2010). On a completely different note, Hall (2011) delves into the fascinating issue of decorated querns. There are also a number of references to the meanings of querns in the archaeological literature pertaining to querns and their structured deposition, that is, their purposeful placement in the archaeological record for reasons that had meaning to the person(s) who placed them. Again, this strand of inquiry has flourished recently as such research has taken a more holistic AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones approach. Merrifield, for example, comments on the “special mystique [that] seems to have been associated with corn-grinding stones” which he presumes is “because of their importance in providing the daily bread” (Merrifield 1987:33–34). Hill (1995:108, 131) refers to the transforming powers of the quern, turning raw materials into usable products, and suggests that it was symbolically linked to the preparation of food, gender and the life cycle of the household. Fendin (2000, 2006) and also Brück (2001:155) see the grinding action of the quern, which gradually wears the stones, as a metaphor for the passage of time and the transformation from life to death as witnessed in human and agricultural life cycles. Links between querns and agricultural fertility are made by Proctor (2002), Heslop (2008:80) and Jodry & Féliu (2009). Lidström Holberg (2004) on the other hand, and also Heslop (2008:75), suggest that the use of and deposition of quernstones was one of the ways in which gender relations were created and expressed. Finally, the author discusses the symbolic properties of querns in her PhD on the structured deposition of querns (Watts 2012, 2014) and Peacock also explores the subject in The Stone of Life (Peacock 2013). The action of grinding and physical properties The published literature, such as that mentioned above, suggests that the symbolic and metaphoric meanings of querns and millstones drew upon not only what the stones were used for and who used them but also how they operated and the grinding action they performed. The first century Roman writer, Seneca, quoting Posidonius (ca. 135–51 BC), refers to the grinding action of querns, describing the tasks of milling and baking as imitating the work of the teeth and stomach (Seneca V Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales 90.22–23). In his poem “The Windmill”, the 19th century American poet Henry Longfellow also makes a similar analogy: “Behold! a giant am I!/Aloft here in my tower,/With my granite jaws I devour/The maize, and the wheat, and the rye,/And grind them into flour.” (Jerrold 19--?:532). Today, for the Betamiliba of West Africa, the correlation between teeth and grinding is a key part of their world view. Their houses are metaphors for the human body and so are constructed of flesh (earth), bone (stone) and blood (water). The door is the mouth and the granaries the stomach. It is perhaps not unexpected, therefore, that just inside the mouth are the teeth, that is the household quern (Tilley 1999:44–45). 55 Physical properties, such as size and weight, are also important. As Parker Pearson and Ramilisonina point out, “the physical properties of materials such as stone, wood, water and fire … resist certain interpretations and invite others. In such cases their materiality may be a significant element of their metaphorical associations” (Parker Pearson & Ramilisonina 1998:310). A quern or millstone is a durable item, harder than the material it grinds. This “invites” such metaphors as “his heart is … as hard as a piece of the nether millstone” (Job 41.24). In the book of Revelation, an angel takes up “a stone like a great millstone, and cast[s] it into the sea, saying, Thus with violence shall that great city Babylon be thrown down, and shall be found no more at all” (Revelation 18.21). We refer figuratively to having a millstone around our neck when describing a heavy burden we bear, which derives from Jesus’s saying, “whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea” (Matthew 18.6). It may be just such a load that is symbolised by the millstone in Albrecht Dürer’s allegorical engraving Melencolia (1514). The picture, which is thought to metaphorically depict waiting for inspiration to strike, is full of symbolism and has been the subject of much discussion and interpretation beyond the scope of this article. Indirect references to this quotation also occur in the lives of some saints. St. Hallvard, patron saint of Oslo, for example, was killed whilst defending a woman accused of theft. The woman was also killed and was buried on the beach. The perpetrators, however, attempted to dispose of St. Hallvard’s body by tying it to a millstone and throwing it into the Drammensfjord. The body, however, refused to sink and consequently their crimes were discovered (Heraldry of the World 2012). St. Piran, patron saint of Cornwall, was also tied to a millstone and thrown off a cliff in Ireland but he did not drown. Instead he floated on the millstone to the Cornish coast, landing safely on Perran Beach (Jones 1997). St. Anastasius the fuller was not so fortunate. He was tied to a millstone and drowned in Salona Bay in AD 304 (Mackie 2003:220). St. Victor of Marseilles, an officer in the Roman army, was martyred on the orders of the Emperor Maximian ca. AD 290 by being crushed between two millstones (Bond 1995:32). However, whereas St. Piran, St. Anastasius and St. Hallvard (see below) are frequently depicted with their millstones (Fig. 1), St. Victor is usually shown with a windmill although the latter was not invented until some 850 years after his death. Susan Watts Fig. 1. St. Anastasius with a millstone around his neck, the symbol of his martyrdom. Cathedral of St. Domnius, Split. Photo: Jocelyn Rendall. Fig. 2. Two saddle querns of different colours, from different sources, found side by side in the ditch of a Bronze Age enclosure at Sigwells, Somerset (centimetre scale). Photo: Susan Watts. The colour of querns Another physical attribute that also appears to come into play, particularly regarding the structured deposition of querns in the prehistoric period, is colour. A number of archaeologists have commented on the colour of querns found in prehistoric contexts in England. Chadwick Hawkes (1969:6), for example, noted that, although the saddle quern and rubber deposited in a Bronze Age pit at Winnall near Winchester, Hampshire were a pair, they were of a dark brown coarse grained sandstone and a white fine-medium grained sandstone respectively. At the Ben Bridge site at Chew Valley Lake, Somerset a probable Neolithic saddle quern of Old Red Sandstone was found with a rubber of Corallian sandstone (Rahtz & Greenfield 1977:202). The combination of the dark sandy colour of the Corallian sandstone and the red of the Old Red Sandstone would have been quite noticeable. Two 56 saddle querns, one of Upper Greensand and the other of a red igneous rock, which were found side by side in the ditch of a Bronze Age metalworking enclosure at Sigwells, Somerset, also present a striking appearance (Fig. 2). The meaning of colour is difficult to quantify. Red is a particularly significant colour with many different meanings. In our own society a red traffic light means stop, red roses are a token of love and a red letter day is a good day but to be in the red (financially) is not good. In the Church of England, red vestments and hangings are used at Pentecost, symbolising the tongues of fire that came down on the disciples. Other colours have meanings too – we go green with envy, feel blue, fall into a brown study and clouds have silver linings. Black is associated with mourning, white with light, purity and weddings (papers in Gage et al. 1999 and Jones & MacGregor 2002 discuss the meanings of colours). AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones The use of different coloured stones, in particular grey, red and white has been noted in the construction of some Scottish stone circles and white quartz is a feature of many prehistoric ceremonial or ritual sites (Darvill 2002, Jones & Taylor 2004:110, Bradley 2005a:106–108). In the Roman world white pebbles symbolised happiness. More recently, in Mesoamerica, green stones were associated with health (Evans 1897:468, Horsfall 1987:346–347). However, as Scarre (2002:238) points out, the significance of the colour may not lie so much in its visual aspect but in the fact that it denotes the origin of the object. The saddle quern from Ben Bridge mentioned above was of local origin but its Corallian sandstone rubber is considered to have come from the Westbury area of Wiltshire, some 32 km away, while the green and red saddle querns at Sigwells derived from sources 15 km to the east and 40 km to the west of the site respectively (Rahtz & Greenfield 1977:202, Tabor 2008:65). The structured deposition of two different coloured quernstones may, therefore, represent a relationship of some form, the different colours symbolising the different parties involved. The site at Sigwells is thought to have been that of a short-lived metalworking and craft fair, where people came together to practice their crafts and ply their trade. The two querns may have been placed in the ditch as part of the “official” closure of the fair, to create a bond between the peoples who met there and, in doing so, to reinforce social identity and kinships (Tabor 2008:61–68). Alternatively, such querns could represent, in coloured form, a particular myth or story, or symbolise a transformation from one state to another (after Young 2006:179). Is it more than coincidence, therefore, that, within a metalworking context, the red and green quernstones from Sigwells are reminiscent of the colours of molten metal, the mould and the bronze object as it emerges from the mould. The meaning behind the deposition, as Tilley (1999:9) says, may only be read by the understanding eye but it is nevertheless obvious, even to the uninitiated, that depositions such as this were made with purpose and intent and that they have a story to tell. Decoration A number of querns and millstones are notable for their decoration. This is an adjunct feature, an adornment that moves the stone beyond its practical milling function, enabling it to operate on a higher plane and increasing its qualitative, rather than its quantitative 57 output. (In this sense the inscriptions on some Roman military querns, which identify the stone as the property of a particular contubernium, cannot be considered as decorations.) Some decoration is purely abstract, such as the lines and swirls inscribed on a number of Iron Age rotary quern stones from Ireland, Wales and Cumbria, England (Griffiths 1951, Caulfield 1977:121–123, Ingle 1987:13). The patterns are similar to that found on contemporary high status metalwork bringing, as Bradley (2005b:101) points out, the work of highly skilled craftsmen into the domestic sphere. Although we may not understand the meaning behind such decoration, it is clear that it raised the respective quern out of the everyday. More explicit perhaps is the meaning behind the phallus found carved upon several fragments of Roman querns, such as that from the extra mural area of the fort at Rocester, Staffordshire. The phallus was an often used image in the Roman world, functioning as both a fertility symbol and a sign against evil (Frere et al. 1983:302, Henig 1984:167, 185–186). The sign of the cross carved on some medieval and later stones, such as that on a medieval quernstone from Dunadd, Argyll, Scotland (Campbell 1987) or that seen by the author on a millstone dated 1846 in Milton Mill, Preston Richard, Cumbria, may also have been intended to ward off evil or to have been a blessing, or to denote that the stones were for grinding a particular product. Another form of decoration takes the form of human heads carved around the spouts of some medieval pot querns. Hall (2011) suggests that these are examples of medieval humour as the ground meal is spewed through the carving’s mouth. Added to which is the possibility that the heads represent those of real people. However, these querns may also have a Christian message. Jesus states (Matthew 15.11) that it is not what goes into a man’s mouth that defiles him but what comes out. Such pot querns, which are not uncommon finds on medieval monastic sites, can thus be seen to teach and amuse at the same time. Anthropomorphic or zoomorphic figures are also a feature of the ornately decorated metates dated ca. AD 500–1500 found in Central America, particularly in Costa Rica, Nicaragua and also Panama. The side panels and legs may be carved with abstract geometric designs, human figures or animals, and occasionally a carved head of a bird or jaguar is added at one end. These elaborate carvings are thought to be related to the function of the metate for grinding maize, or chocolate, and to have been used in ceremonies and rituals concerned with agricultural fertility and the harvest (Precolumbian Stone 2011). Susan Watts Fig. 3. A “sleeping fox” quern from Merona, northern Italy. The quern, which was used for grinding salt, is thought to date to the 17th century. Photo: Guy Clausse. There is also presumably a meaning behind the carvings of curled-up, sleeping foxes that are found on the upper stones of a particular type of post-medieval/ early modern rotary quern that was used for grinding salt (Fig. 3). Examples are known from northern Italy and the Auvergne, France and there is also one on display in Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire, which probably originated on the continent. Two further examples, on which the fox has more the appearance of a hound have also come to light recently in London. Again, these may have come from the continent (Watts 2011:342, Guy Clausse, pers. comm., John Cruse, pers. comm.). At the time of writing, a specific link between querns and salt and foxes/hounds has not come to light but it could perhaps derive from a local folk tale or relate to the maker’s name. Symbols of men, women and children Although men may use querns in particular circumstances, such as in monastic institutions or for grinding particular products such as tobacco, historic and ethnographic evidence indicates that querns as tools for preparing food are very much the province of women (for example Livingstone 1887:384–387, Richards 1939: 91–104, Hamilton 1980:5–6, 8, Englund 1991, Haaland 1997:378–379, Curtis 2001:115–116, Ertug-Yaras 2002). It is through such gender-related tasks that the distinctiveness of being female or male is maintained. In classic Mayan culture, ca. AD 250–900, the role of women as providers of food was subtly reinforced through the production of ceramic figurines depicting women at domestic tasks including corn grinding (Casalis 1861:141, Joyce et al. 1993, 58 Lidström Holmberg 2004:227). Thus querns used in a domestic context for the preparation of food can be seen as symbolic of women, home and the family. In early 20th century rural Mexico, for example, it was one of the four items – hearth, griddle, grinding stone and pot – considered necessary for the house (Brumfield 1991:237). It is not until grinding becomes a mechanised process that it becomes acceptable for men to partake in, and indeed take over, the role of miller. The association between querns and women is further strengthened in some societies by lengthy grinding sessions held as part of the rituals to celebrate female rites of passage. These sessions may be communal, as with the Lala of Nigeria where all the women of the village come together to grind corn to mark the onset of puberty of a young girl (Kirk-Greene 1957). Saddle querns are placed around the inside of a specially erected shelter in the centre of the village and the women grind all day, keeping time to the beat of drums and singing. Within the Hopi tribe of northeast Arizona, however, it is customary for the girl only to perform the grinding ritual, grinding white, blue, red, yellow and black maize within a darkened room over a period of four days. A similar grinding ritual is also performed by a Hopi bride before her wedding (Bradfield 1973:34–37). In both Lala and Hopi societies, the use of querns in such contexts can be seen as an affirmation and symbol of womanhood. The transition from girl to woman is expressed symbolically through the transformation of corn to meal but a proficiency at grinding also demonstrates that she is well able to provide for her family (Katz 2003:46, Lidström Holmberg 2004:227). Although a clear link can be seen between querns and women, this is but one way in which gender is enacted through querns and millstones. Querns and millstones comprise two stones which are brought together for the action of grinding and are seen, therefore, as an ideal metaphor for the expression of gender relations. The movement of the upper stone of a saddle quern forward and back across the lower stone may be seen to have an overtly sexual meaning, with the lower stone being seen as female and the upper stone as male (Lidström Holmberg 2004:225–228). The playing out of the male/female sexual relationship can also be seen in the rotary quern, the lower stone this time taking the male role. Millstones are still described in feminine terms in modern traditional milling terminology. The central hole in the stone is called the eye, the midsection of the stone the breast and the outer section the skirt. Likewise, the fitting on top of the spindle AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones that knocks against the shoe, which hangs below the hopper, to feed the grain into the eye of the runner stone is called a damsel. It is often stated that the name is due to the fact that it chatters (clatters) as it turns! In some communities, however, such as the Minyanka in Mali, the upper stones of saddle querns represent children (Caroline Hamon, pers. comm.). This may be due to the smaller size of the rubbing stone and the fact that it is this stone which a woman has most contact with as she works. Lidström Holmberg (2004:229–230) makes an interesting association between the deposition of upper stones in adult graves and lower stones in the graves of children at the early Neolithic sites at Fågelbacken and Östra Vrå, Sweden. In western European Linearbandkeramik and postLinearbandkeramik cemeteries, querns tend to be found in the graves of women and children, while at Khirokitia, Cyprus there was an apparent preference for querns with male rather than female burials (Brun 2001:116, Caroline Hamon, pers. comm.). Gimbutas (1991:133) also noted that in central Europe querns are found with both male and female Neolithic burials although it is not clear whether these are upper and/or lower stones. That direct correlations between male/ female/child and upper/lower stones should perhaps not be presumed is also demonstrated by Indian nonvedic birth rituals in which the upper stone represents both child and mother goddess. Painted and dressed, the stone is passed around the cradle by the most senior woman in attendance before being laid beside the baby in a ceremony intended to bestow blessings on the child (Kosambi 1965:46). In addition, not all Neolithic burials contain querns and northern European chambered tombs, some of which have been found to utilise querns within their construction, held multiple disarticulated burials. There are, however, other reasons to account for the presence of querns in funerary contexts. They could have been placed as grave goods to provide sustenance in the afterlife or have been used in the preparation of a funerary feast and subsequently taken out of use. Alternatively, they may symbolise the cycle of life and death and regeneration as represented by the transformation of grain to flour (see below) (Hill 1995:108, Bradley 2005b:107). It is also possible, of course, that the quern fragments reused in the construction of funerary monuments simply represent the reuse of useful pieces of stone but, given that such burial or memorial structures are generally located away from domestic sites, the implication is that the stones were specially brought to these sites. 59 Symbols of the harvest and fertility With the beginnings of agriculture in the Neolithic period the harvest took on a new meaning, although autumn would always have been a time of plenty in terms of wild fruits, nuts and seeds. The cultivation of grain is seen as symbolising mankind’s triumph over nature (Ramminger 2008:42). The quern may be seen, therefore, as a symbol of that triumph, representing cultured nature. This theme finds expression in Cezanne’s painting, Woods with Millstone (1898–1900) in which the millstone represents man amidst a forest of natural chaos. With cultivation, however, came a new regime of preparing the ground, sowing the seed and harvesting and storing the grain both for consumption and as seed corn for the following year. Communities became “bound…to the soil” (Gimbutas 1982:11). In the Near East the change from a hunter-gatherer society to one based on farming is recorded in the Bible. When God casts Adam and Eve from the garden of Eden, in which they had been given the fruit of all the trees, he tells them that the ground is cursed and “Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field; In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread” (Genesis 2.16, 3.2, 17–19). To subsistence based communities the success of the harvest is paramount. A poor harvest leads to hardship, even starvation and death. It is important, therefore, that the ground is prepared and crops sown at the most auspicious and propitious times. To this end, in the prehistoric period and later, the gods were consulted and appropriate gifts and offerings made (Green 1997:37). Querns, as a key part of the process that turns grain into meal, may have been seen as symbolic of grain and of the harvest and thus considered suitable offerings, on one hand for the success of the harvest, or on the other hand in recompense for its failure. This offers one potential explanation for the presence of quernstones as structured deposits in Iron Age grain storage pits on sites in southern Britain. Alternatively, they may have been propitiatory offerings for pits that had lost their watertight seal and whose contents had gone mouldy (Cunliffe 1992, Watts 1999). The lurid colours and the smell of the mouldy grain may have been seen as indicative of the presence of evil spirits, reason enough for the abandonment of the pit and the placing of propitiatory gifts (Reynolds 1979:76, Watts 1999). Gimbutas (1987:20) makes reference to large flat stones, dedicated to or representing Ops, a Roman goddess of earth fertility, which were stored in pits Susan Watts and covered with straw. They were taken out once a year during the harvest season; in the Roman world her festival was celebrated on 25 August (Jordan 2002:190). It is tempting to link this practice to the complete saddle quern found placed upside down in a Neolithic pit at Etton, Cambridgeshire and also at Milsoms Corner, Somerset. That from Etton appeared to have been packed in leaves and twigs, while that from Milsoms Corner was laid upon a bed of carbonised material (Pryor 1998:22, Richard Tabor, pers. comm.) It seems they were being stored safely underground, which raises the possibility that, like the stones mentioned by Gimbutas, they were taken out for use following the harvest. This use may have been at once both practical and symbolic (Bradley 1987:351). The decorated metates from Central America mentioned above are thought to have performed similar conjoined symbolic and practical functions. Symbols of life, death and rebirth During the milling process, however, raw, unusable and inedible materials are ground into usable and edible products. This is a particularly important symbolic process in relation to grain, which is itself a powerful symbol of life, death and resurrection (John 12.24). As the grain is ground so it is effectively killed. This is wellillustrated in the language of the Hopi, for whom the life cycle of the maize plant is metaphorically linked to that of humans. The word tuqyakni means “others killed” and derived from tuu-+qöya (the plural form of to kill) and –kna (pounded maize kernels) (Black 1984:282). The killing of the grain is the subject of “John Barleycorn”, an English folksong thought to be the survival of a myth relating to the slaying of a corn god (Vaughan Williams & Lloyd 1959:56–57, 116). John Barleycorn is buried in the ground and presumed dead but he rises up green and living. However, he is cut down in the prime of life. In the tortuous treatment he subsequently receives, the miller, we are told, plays his part by grinding John Barleycorn between two stones. The story of John Barleycorn echoes the fate of Mot, an ancient Canaanite god of natural adversity, drought and death. Mot traps Baal, a god of rain and vegetation, in the underworld and kills him. Anat, sister of Baal, and goddess of fertility and war, travels to the underworld to avenge his death. She cleaves and winnows Mot and burns him in a fire before grinding him in a mill and scattering him over the fields. Her actions revive Baal and in due course Mot is also restored to life 60 (Jordan 2002:167, Anon 2010). The bones of Tammuz, a Sumerian fertility god are similarly ground in a mill and scattered to the wind. The story of Tammuz comes from a Nabataean text ca. 300 BC–AD 100 and may derive from the cosmological conflict between Mot and Baal. This latter myth is recorded on tablets dated ca. 1200 BC from Urgarit, an ancient port at Ras Šamra in northern Syria (Santillana & Dechend 1969:91, Tolley 1994–1997:74) but again it is likely to be more ancient in origin, potentially rooted in the Neolithic period and the beginnings of agriculture in the Near East. As Graves (1959:v, viii) comments, myths were not only a way through which people sought to understand the natural world around them but also, in a fantastical way, explained and justified earthly events, including migrations and the introduction of new or foreign ideas. Thus the story of Mot represents the natural annual cycle of rain and drought and the growth and death of vegetation in the region onto which the agricultural cycle of sowing, growing and harvesting is superimposed (Anon 2010). Through its death in the mill, however, grain is transformed from an indigestible material into a potentially life-giving product. The act of milling can be seen, therefore, as both destructive and creative (Stone 2010). As such it echoes the natural order, the constant and rhythmic change between creation and destruction, birth and death, which it is suggested underlay the belief system of the European Neolithic (Gimbutas 1987:12). This is witnessed not just in the natural world but in the agricultural year and also in human lives. The quern/millstone, a familiar everyday object, is an ideal medium, therefore, through which changes in the human state can be explained (Brück 2001:155). The transformation through grinding from raw material to refined product, from one state to another, provides the perfect metaphor not only for the transition from girl to woman but also from life to death and from death to rebirth. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that the act of milling is also a key part in some creation myths. In Mexican mythology, the bones of previous incarnations of mankind procured by Quetzalcoatl from the underworld are ground by the goddess CihuacoatlQuilaztli. The ground bone is mixed with the blood of the gods and from the mixture the current generation of humanity is made (Santillana & Dechend 1969:93, Jordan 2002:53, 212). In Norse mythology the flesh of primeval giants is ground into mould, that is the fertile soil in which vegetation grows and into the sand on the sea shore (Rydberg 1887:79–80). AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones Symbols of prosperity and adversity The transformation metaphor becomes particularly potent when considered in the light of the invisible grinding process that takes place between the two stones of a rotary quern or millstones. When the rotary quern was first introduced in the Iron Age this would have been, as Heslop says a “startling magical innovation” after the very visible crushing of the grain on a saddle quern (Heslop 2008:18). The novelty would have worn off as the rotary quern became a more familiar, everyday tool but the idea of an invisible, magical transformation may have lingered in metaphorical form. It is this unseen transformation that may lie at the root of tales of magical mills that grind either prosperity or adversity. The Grottasöngr, recorded in the Prose Edda compiled by the 12th/13th century Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson and also in the Poetic Edda, a collection of 13th century Norse poems, tells of a large quern called Grotti that belonged to King Frodi. Grotti was turned by two giant-maidens, Fenia and Menia, who ground wealth and happiness for Frodi. In his greed Frodi allowed Fenia and Menia little rest and in revenge they ground an army to attack him. In the Poetic Edda they continue to grind on furiously until their frenzied grinding pulls the frame on which the quern sits to pieces and the stones are broken. In the Prose Edda, however, the leader of the attacking army is a sea-king called Mysing who takes Fenia and Menia on board his ship and bids them grind salt, which they did until the ship sank and they are grinding still, which explains why the sea is salt. According to Orcadian tradition the quern lies in the Pentland Firth (Johnston 1910, Magnússon 1910, Mackenzie 1912:246–249, Tolley 1994–1997:67–68). Later folk tales of Scandinavian and Germanic origin pick up on the theme of a magic quern that will grind anything that is asked of it and, likewise, end with the quern grinding salt at the bottom of the sea (for example Mackenzie 1912:249–253). The Finnish tale, The Kalevala, also features a magical device called the Sampo which is thought by some authors to be a mill. The word Sampo, however, appears to have originally signified a pillar and to relate to the world pillar around which the heavens turn and the seasons are regulated (Tolley 1994–1997:65–67). The Sampo had three sides that produced corn, salt and coins respectively. It too was eventually destroyed and the pieces of it were dispersed, some to the sea whence come the riches of 61 the sea, some to the land of Vainomoinen to increase the soils fertility but the far north only got a small piece hence why it is such an unproductive region (Tolley 1994–1997:63–67, Stone 2010). In these tales the quern provides its wares magically, requiring no input. The quern may be a symbol, therefore, of the earth and the riches it provides (Stone 2010). However, these tales also contain a warning. If the quern/earth is misused or mistreated it will grind/ produce harm and ruin instead. The mystic mill The unseen transformation from grain to flour is also manifest in medieval Christian allegory, grain and bread being a source of spiritual as well as bodily nutrition. In the mystic or Eucharistic mill the laws of the Old Testament prophets (grain) are transformed, through Christ (the millstones) into the teachings of the New Testament (flour/communion wafers). Images of the mill from the 14th and 15th centuries typically show a geared mill turned by a double cranked handle. Grain is poured into the mill by the four evangelists and the mill is turned by the apostles. Waiting to receive the ground product are Fathers of the Latin church, Ambrose, Augustine, Gregory the Great and Jerome (Moffet 2003:215, Roberts 2005, Worthen 2006:269–270). Rather different, however, is the mystic mill depicted on one of the capitals in the nave of the church at Vézelay Abbey, Burgundy, France. The 12th century carving shows two figures, one either side of the mill. The figure on the left pouring the grain into the mill is thought to be Moses while that on the right, collecting the ground meal in a sack, is probably St. Paul (Moffet 2003:215, Ambrose 2006). The 16th century reformation of the church also found expression in contemporary allegorical drawings of mills such as Johann Fischart’s Die Grille Krotestisch Mül zur Römischen Frucht (1577) in which priests are ground into strange creatures (Gleisberg 1975:146–147, Fig. 35). Illustrations and stories of mills that transform are found in secular as well as religious life. The ballad “The Miller’s Maid Grinding Old Men Young Again”, for example, begins “Come old, decrepid, lame, or blind,/Into my mill to take a grind”. The mill, depicted on a woodcut of ca. 1720, shows a procession of elderly men climbing happily into the mill which is turned by a young woman. Other young women wait beside the mill to claim each rejuvenated man as he emerges from Susan Watts refer to being on a treadmill today when work or life seems relentless or monotonous. The treadmill as a form of punishment also brings to mind the story of Samson who, when captured by the Philistines, was forced to grind in the prison house (Judges 16.21). In Samson’s case, however, he would have been grinding grain into flour on a saddle quern. This would have been considered a degrading task in a world where milling was an occupation fit only for women and slaves. The cosmic mill Fig. 4. The circular motion of the upper stone of a rotary quern or millstone can be likened to the turning of the heavens, the stationary lower stone signifying the earth. Photo: Susan Watts. the mill (Jewitt 1869–1870:86–87). In The Woman Mills of Tripstrill, however, a musical for Shrove Tuesday written by G.A. Bredelin ca. 1787, it is old women who are ground young again. Following the exhortations of the miller, five men bring their elderly wives to the altweibermühle for rejuvenation. Unfortunately, for the men, their new, young wives want nothing more to do with them. Stolprian, the clown, seeing this result then brings his wife, who he wishes to be rid of, to the mill but the tables are turned when she refuses to leave him (Gleisberg 1975:148–149, Wikipedia 2012). A ditty in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, dated 30 August 1823, makes reference to the altweibermühle: “The gossips of yore of a Miller made mention,/Who ground the OLD young, and their beauty renew’d./ But how vastly superior the modern invention,/Of a Mill where the NAUGHTY FOLKS grind themselves GOOD!”. The mill that ground “the naughty folks good” was not a corn mill but a treadmill or a treadwheel developed by engineer Sir William Cubitt in 1817 as a means of reforming prisoners. The treadmill referred to in this instance is probably the one installed in Bodmin gaol in Cornwall. Long, gruelling hours would have been spent by prisoners on the mill, which was often geared to a water pump or millstones. It was thus considered to be a beneficial and productive form of hard labour at a time when idleness, particularly in prisoners, was thought to be a sin (Shayt 1989). We still 62 The saddle quern was the sole means of grinding grain for many thousands of years. The advent of the rotary quern in the Iron Age, therefore, was a remarkable innovation in milling technology. Current evidence suggests that it originated in Catalonia, the serendipitous concurrence of an increase in grain production in the region, the use of the potter’s wheel and an increasing use of iron tools providing the inspiration and means necessary for the development of a new and more efficient milling device (Alonso 1997:15–19, 2002:111, 122, Aquilué et al. 2000, Watts 2012). The transference of the forward and backwards motive operation of the saddle quern to the circular motion of the rotary quern subsequently enabled adaptation to animal, water and wind power. It also enabled the development of new mythologies and meanings based on rotary motion (Fig. 4). As shown below, the turning of the upper stone came variously to symbolise the turning of the heavens with its revolving constellations or the turning of the earth or the passage of time itself. Although Santillana & Dechend (1969) and also Kelly (2002) attempt to push the origins of the cosmic mill back to the Bronze Age or earlier it cannot predate the origin of the rotary quern. The earliest reference to the cosmic mill appears to be a comment made by the character Trimalchio in the Satyricon written by Petronius, a courtier of the Emperor Nero, in the first century AD. Following a description of the zodiac, Trimalchio declares “so the world turns like a mill[stone], and always brings some evil to pass, causing the birth of men or their death” (Petronius Satyricon 39). According to Norse mythology, the cosmos was turned by Mundilfoeri, the one who turns the mill and through whom the timing of the seasons was ordered and the 9th century Arab astronomer, al-Farghani likewise described the revolving of the sky around the Pole Star as “like the turning of a mill” (Rydberg 1887:81, Worthen 2006:260, Stone 2010). In Aelfric’s Homilies, AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones written in the 10th century, there is a reference to a quernstone that turns continually but goes nowhere. The quernstone symbolises the world which Aelfric says “circulates in errors” (Thorpe 1844:515). The mill is also used as a metaphor for life and the passage of time in a little 19th century Sunday School publication called The Old Miller and His Mill (Pearse undated) in which the miller (time) indifferently grinds out not grain but people both good and bad. This theme is echoed in Longfellow’s poem, “Retribution”: “Though the mills of God grind slowly, yet they grind exceeding small;/Though with patience he stands waiting, with exactness grinds he all” (Jerrold 19--?:603). In other words, whatever one takes to the mill (life) one will get back in kind. Millstones in heraldry Finally, millstones also appear as charges on coats of arms. Three millstones, for example, featured on the original coat of arms of the Millington family of Millington, Cheshire (Bennett & Elton 1899:233). The coats of arms of number of European towns and cities also include millstones in each case symbolising a particular aspect of that place. They may represent, for example, the name such as Porto de Mos, Portugal or an actual mill with which the town is associated, such as at Beinhorn, Germany or, in the case of Hyllestad, Norway, the millstone trade (Heraldry of the World 2012). Oslo, however, does not have a coat of arms but a town seal which dates to at least the 15th century. The main figure on the seal is St. Hallvard who, as mentioned above, was killed protecting a woman and whose murderers attempted to dispose of his body by tying it to a millstone and throwing it into the fjord (Heraldry of the World 2012). St. Hallvard is depicted on the seal with the dead woman at his feet, the arrows with which he was killed in his left hand and in his right hand, a millstone. brief exploration shows, querns and millstones can be representative of: • • • • • • • gender and womanhood harvest and plenty desolation and famine life and/or death transformation the world/the heavens people and places These esoteric meanings are drawn from all facets of the materiality and functionality of querns and millstones. These include not only what they were used for and who used them but also the physical action of grinding and the transformative process from raw material to refined product that takes place between the two stones, as well as their size, weight or colour. Such a wide variety of symbolic and metaphoric aspects originate, of course, in different times and places and will have developed in response to specific cultural situations. We can only theorise regarding the meaning of querns in the prehistoric period but nevertheless it is likely that some later symbology will have derived from earlier traditions even though the connections that link them are now broken (Green 1999). However, similar symbologies may also have been created by different societies facing similar concerns, over the harvest for example, and asking similar questions. What is apparent is that, through the use of common, everyday objects such as querns and millstones, difficult concepts such as the progress of the seasons and the reconciliation of the Old to the New Testament were explained in easy to understand terms. In turn, such symbolism highlights the importance of querns and millstones to communities for milling grain. As Worthen says, paraphrasing Freud, “sometimes a mill [or quernstone] is just a mill [or quernstone] but oftentimes it is a great deal more” (Worthen 2006:278). Acknowledgements Conclusions As tools for grinding grain, querns and millstones are of prime importance to subsistence-based communities. As such indispensible and consequently familiar tools it is perhaps not surprising that throughout the 12,000 years or so of their history they should have acquired symbolic and metaphoric functions in conjunction with their practical, everyday milling function. As this 63 I would like to take this opportunity to thank John Cruse for alerting me to the sleeping fox querns from London, Dr. Richard Tabor for details of the Neolithic pits at Milsoms Corner, Somerset, Dr. Caroline Hamon for sharing details of her research in Mali with me, Professor David Peacock for allowing me a preview of his book, The Stone of Life and Jocelyn Rendall and Guy Clausse for Fig. 1 and 3 respectively. Susan Watts References All Biblical quotations are taken from the Authorised King James Version first translated into English in 1611. The in-text references are to book, chapter and verse. Adams, J.L. 2002. Ground stone analysis. A technological approach. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. Alonso, N. 1997. Oriegen y expansion del molino rotativo bajo en el mediterraneo occidental. In Meeks, D. & Garcia, D. (eds.). Techniques et economie Antiques et Médiévales: le temps de l’innovation, pp. 15–19. Editions Errance, Paris. Alonso, N. 2002. Le moulin rotatif manuel au nord-est de la Péninsule Ibérique. In Procopiou, H. & Treuil, R. (eds.). Moudre et broyer. Vol. 2, pp. 183–196. Le Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, Paris. Ambrose, K. 2006. The ‘mystic mill’ capital at vézelay. In Walton, S.A. (ed.). Wind & water in the Middle Ages, pp. 235–258. Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Tempe. Anon 2010. Encyclopedia of myths. http://www. mythencyclopedia.com (accessed 29.01.2010) Aquilué, X., Castanyer, P., Santos, M. & Tremoleda, J., 2000. Guidebooks to the museu d’arqueologia de Catalunya, Empúries. Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya, Edicions El Mèdol, Tarragona. Barboff, M., Sigaut, F., Griffin-Kremer, C. & Kremer, R. (eds.) 2003. Meules à grains. Actes due colloque international la ferté-sous-jouarr 16–19 mai 2002. Ibis Press, Paris. Barnwell, E.L. 1881. Querns. Archaeologia Cambrensis, fourth series 12, 45, 30–43. Bennett, R. & Elton, J. 1898–1904. History of corn milling. Vols. 1–4. Simpkin, Marshall and Company Ltd, London. Black, M.E 1984. Maidens and mothers. An analysis of Hopi corn metaphors. Ethnology 23, 4, 279–288. Bond, C.J. 1995. Medieval windmills in south-western England. The wind and watermill section, The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, Occasional Publication 3, London. Bradfield, R.M. 1973. A natural history of associations. Vol. 2. Gerald Duckworth & Company Limited, London. Bradley, R. 1987. Stages in the chronological development of hoards and votive deposits. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 53, 351–362. Bradley, R. 2005a. The moon and the bonfire. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Bradley, R. 2005b. Ritual and domestic life in prehistoric Europe. Routledge, London. Brumfield, E.M. 1991. Weaving and cooking. Women’s production in Aztec Mexico. In Gero, J.M. & Conkey, M.W. (eds.). Engendering archaeology. Women and prehistory, pp. 224–251. Basil Blackwell Ltd., Oxford. Brun, A. Le 2001. At the other end of the sequence. The Cypriot Aceramic Neolithic as seen from Khirokitia. In Swiny, S. (ed.). The earliest prehistory of Cyprus. From colonization to exploitation, pp. 109–117. American Schools of Oriental Research, Boston. Brück, J. 2001. Body metaphors and technologies of transformation in the English Middle and Late Bronze Age. 64 In Brück, J. (ed.). Bronze Age landscapes,tTradition and transformation, pp. 149–160. Oxbow, Oxford. Bucur, C. 1979–1983. Moară de Mînă în Istoria civilizației tehnice a poporului Român. Cibinium, 63–96. Campbell, E. 1987. A cross-marked quern from Dunadd and other evidence for relations between Dunadd and Iona. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 117, 105–117. Carelli, P. & Kresten, P. 1997. Give us this day our daily bread. A study of Late Viking Age and Medieval quernstones in South Scandinavia. Acta Archaeologica 68, 109–137. Casalis, E. 1861. The Basutos; or, twenty-three years in South Africa. James Nisbet & Co., London. Caulfield, S. 1977. The beehive quern in Ireland. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 107, 104–138. Chadwick Hawkes, S. 1969. Finds from two Middle Bronze Age pits at Winnall, Winchester Hants. Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society 26, 5–18. Colville, J. 1892. The rural economy of Scotland in the time of burns. Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow 23, 120–152. Crawford, O.G.S. 1953. Archaeology in the field. Phoenix House Ltd., London. Cunliffe, B. 1992. Pits, Preconceptions and propitiation in the British Iron Age. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11, 1, 69–83. Curtis, R.L. 2001. Ancient food technology. Brill, Leiden Curwen, E.C. 1937. Querns. Antiquity 11, 133–150. Darvill, T. 2002. White on blonde, quartz pebbles and the use of quartz at Neolithic monuments in the Isle of Man and beyond. In Jones, A. & Macgregor, G. (eds.). Colouring the past, pp. 73–91. Berg, Oxford. Englund, R.K. 1991. Hard work where will it get you? Labor management in Ur III Mesopotamia. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 50, 4, 255–280. Ertug-Yaras, F. 2002. Pounders and grinders in a modern central Anatolian village. In Procopiou, H. & Treuil, R. (eds.). Moudre et broyer. Méthodes, Vol. 1, pp. 211–225. Le Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, Paris. Evans, J. 1987. The ancient stone implements, weapons and ornaments of Great Britain. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Fendin, T. 2000. Fertility and the repetitive rartition. Lund Archaeological Review 6, 85–97. Fendin, T. 2006. Grinding processes and reproduction metaphors. In Andrén, A., Jennbert, K. & Raudvere, C. (eds.). Old Norse religion in long-term perspectives, pp. 159–163. Nordic Academic Press, Lund. Frankel, R. 2003. The Olynthus mill, its origin, and diffusion. Typology and distribution. American Journal of Archaeology 107, 1–21. Frere, S.S., Hassall, M.W.C. & Tomlin, R.S.O. 1983. Roman Britain in 1982. Britannia 14, 280–356. Gage, J., Jones, A., Bradley, R., Spence, K., Barber, E.J.W. & Taçon, P.S.C. 1999. Viewpoint, what meaning had colour in early societies? Cambridge Archaeological Journal 9, 1, 109–126. Gerrard, C. 2003. Medieval archaeology. Routledge, London. Gimbutas, M. 1987. The earth fertility goddess of old Europe. Dialogues D’histoire Ancienne 13, 1, 11–69. AmS-Skrifter 24 The symbolism of querns and millstones Gimbutas, M. 1991. The civilization of the goddess. The world of old Europe. Harper, San Francisco. Gleisberg, H. 1975. Aus der Geschichte der Mühle. In Zintzen, H. (ed.). Alles ist schon einmal dagewesen, pp. 107–157. Roche, Basel. Graves, R. 1959. Introduction. In Guirand, F. (ed.). Larousse encyclopedia of mythology, pp. v–viii. Batchworth Press Limited, London. Green, M.J. 1997. Exploring the world of the druids. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London. Green, M.J. 1999. Back to the future. In Gazin-Schwartz, A. & Holtorf, C.J. (eds.). Archaeology and folklore, pp. 48–66. Routledge, London. Griffiths, W.E. 1951. Decorated rotary querns from Wales and Ireland. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 14, 46–91. Haaland, R. 1997. Emergence of sedentism. New ways of living, new ways of symbolizing. Antiquity 71, 374–385. Hall, M.A. 2011. Sideways. Face-play on the edge of some Scottish pot-querns, or a funny thing happened on the way to the abbey. In Hardwick, P. (ed.). The playful middle ages, meaning of play and plays on meaning, essays in memory of Elaine C. Block, pp. 93–123. Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe 23, Brepols, Turnhout. Hamilton, A. 1980. Dual social systems, technology, labour and women’s secret rites in the eastern desert of Australia. Oceania 51, 1, 4–16. Hamon, C. & Gall, V. Le 2013. Millet and sauce. The uses and functions of querns among the Minyanka (Mali). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32, 109–121. Hamon, C. & Graefe, J. (eds.) 2008. New perspectives on querns in Neolithic societies. Archäologische Berichte 23, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte e.V., Bonn. Hayden, B. (ed.) 1987. Lithic studies among the contemporary highland Maya. The University of Arizona Press, Tuscon. Henig, M. 1984. Religion in Roman Britain. B.T. Batsford Ltd., London. Heraldry of the World 2012. Heraldry of the world. http://www. ngw.nl (accessed 20.08.2012) Heslop, D.H. 2008. A corpus of beehive querns from northern Yorkshire and southern Durham. Yorkshire Archaeological Society Occasional Paper 5, Yorkshire. Hill, J.D. 1995. Ritual and rubbish in the Iron Age of Wessex. BAR British Series 242, Oxford. Horsfall, G.A. 1987. A design theory perspective on variability in grinding stones. In Hayden, B. (ed.). Lithic studies among the contemporary highland Maya, pp. 332–377. The University of Arizona Press, Tuscon. Ingle, C.J. 1987. The production and distribution of beehive querns in Cumbria. Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Archaeological and Antiquarian Society 87, 11–17. Jerrold, W. 19--? Longfellows poetical works. Collins’ Cleartype Press, London. Jesch, J. 2010. Norse myth in medieval Orkney. http://www. dur.ac.uk/medieval.www/sagaconf/fesch.htm (accessed 02.06.2010) Jewitt, L. 1869. Derby signs described and illustrated. The Reliquary 10, 81–87. Jodry, F. & Féliu, C. 2009. Nouvelles données sur les dépôts de meules rotatives. Deux exemples de la tène finale en Alsace. 65 In Bonnardin, S., Hamon, C., Lauwers, M. & Quilliec, B. (eds.). Réalités archéologiques et historiques des dépôts de la préhistoire à nos jours 22, pp. 69–76. Éditions Association pour la Promotion et la Diffusion des Connaissances Archéologiques, Antibes. Johnston, A.W. 1909–1910. Grotta Söngr and the Orkney and Shetland quern. Saga-Book of The Viking Club 6, 296–304. Johnston, A.W. 1910. Grotti Finnie and Grotti Minnie. Old-Lore Miscellany 3, 8–10. Jones, A. & MacGregor, G. 2002. Colouring the past. Berg, Oxford. Jones, A.M. & Taylor, S.R. 2004. What lies beneath…St. Newlyn East & Mitchell. Cornwall County Council, Truro. Jones, K.I. (ed.) 1997. Cornwall’s legend land. Vol. 1. Oakmagic Publications, Penzance. Jordan, M. 2002. Encyclopedia of Gods. Kyle Cathie Limited, London. Joyce, R.A., Davis, W., Kehoe, A.B., Schortman, E.M., Urban, P. & Bell, E. 1993. Women’s work. Images of production and reproduction in pre-Hispanic southern central America. Current Anthropology 34, 3, 255–274. Katz, E. 2003. Le metate, meule dormante du Mexique. In Barboff, M., Sigaut, F., Griffin-Kremer, C. & Kremer, R. (eds.). Meules à grains, pp. 32–50. Ibis Press, Paris. Kelly, J. 2002. Querns and the cosmos. Quern Study Group Newsletter 6, 9–14. Kirk-Greene, A.H.M. 1957. A Lala initiation ceremony. Man 57, 9–11. Kosambi, D.D. 1965. The culture and civilisation of ancient India in historical outline. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. Kozmin, P.A. 1917. Flour milling. George Routledge & Sons Ltd., London. Translated by Falkner, M. & Fjelstrup, T. from Russian. Lidström Holmberg, C. 2004. Saddle querns and gendered dynamics of the Early Neolithic in mid central Sweden, arrival. Coast to Coast 10, 199–231. Livingstone, D. 1887. A popular account of Dr. Livingstone’s expedition to the Zambesi and its tributaries and of the discoveries of Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa 1858–1864. John Murray, London. Mackenzie, D.A. 1912. Teutonic myth and legend. http:// www.sacred-texts.com/new/tml/tml128.htm (accessed 02.06.2010) Mackie, G.V. 2003. Early Christian chapels in the west. Decoration, function and patronage. University of Toronto Press, Toronto. Magnússon, E. 1910. Grøttasongr. The stone of the quern grotte. Parts 1 and 2. Old Lore Miscellany 3, 139–150 and 237–253. Merrifield, R. 1987. The archaeology of ritual and magic. B.T. Batsford, London. Moffett, M. 2003. The mystic mill from Vézelay. In Moffett, M., Fazio, M.W. & Wodehouse, L. (eds.). A world history of architecture, pp. 215. Laurence King Publishing Ltd., London. Moritz, L.A. 1958. Grain-mills and flour in classical antiquity. Clarendon Press, Oxford. OED Online 2012. Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com (accessed 17.08.2012) Susan Watts Parker Pearson, M. & Ramilisonina 1998. Stonehenge for the ancestors, the stones pass on the message. Antiquity 72, 308–326. Peacock, D.P.S. 1987. Iron Age and Roman quern production at Lodsworth, West Sussex. The Antiquaries Journal 67, 61–85. Peacock, D.P.S. 2013. The stone of life. The archaeology of querns, mills and flour production in Europe up to c. AD 500. Southhampton Monographs in Archaeology New Series 1, Highfield Press, Chandlers Ford. Pearse, M.G. undated. The old miller and his mill. Wesleyan Conference Office, London. Precolumbian Stone 2011. http://precolumbianstone.com (accessed 18.08.2011) Procopiou, H. & Treuil, R. 2002. Moudre et broyer. Vols. 1–2. Le Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, Paris. Proctor, J. 2002. Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age placed deposits from Westcroft Road, Carshalton: their meaning and interpretation. Surrey Archaeological Collections 89, 65–103. Pryor, F. 1998. Etton. Excavations at a Neolithic causewayed enclosure near Maxey, Cambridgeshire. English Heritage Archaeological Report 18, London. Rahtz, P.A. & Greenfield, E. 1977. Excavations at Chew Valley Lake, Somerset. Department of the Environment Archaeological Report 8, London. Ramminger, B. 2008. Quern requirement and raw material supply in Linearbandkeramik settlements of the Mörlener Bucht, NW Wetterau, Hesse. In Graefe, J. & Hamon, C. (eds.). New perspectives on querns in Neolithic societies, pp. 33–44. Archäologische Berichte 23, Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühgeschichte e.V., Bonn. Reynolds, P.J. 1979. Iron-Age farm, the Butser experiment. Colonnade Books, London. Richards, A.I. 1939. Land, labour and diet in northern Rhodesia. Oxford University Press, London. Roberts, N. 2005. Some eucharistic mills. Proceedings of the twentieth mill research conference, pp. 3–10. Mills Research Group, Manningtree. Rydberg, V. 1887. Teutonic mythology. Translated by R.B. Anderson http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/-sczsteve/Rydberg. pdf (accessed 05.08.2013) Santillana, G. de & Dechend, H. von 1969. Hamlet’s mill. http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/hamlets_mill (accessed 25.06.2010) Scarre, C. 2002. Epilogue, colour and materiality in prehistoric society. In Jones, A. & Macgregor, G. (eds.). Colouring the past, The significance of colour in archaeological research, pp. 227–242. Berg, Oxford. Shaffrey, R. 2006. Grinding and milling. A study of RomanoBritish rotary querns and millstones made from Old Red Sandstone. BAR British Series 409, Oxford. Shayt, D.H. 1989. Stairway to redemption, America’s encounter with the British Prison Treadmill. Technology and Culture 30, 4, 908–938. Stone, A. 2010. The cosmic mill. http://www.inditogroup.co.uk/ edge/cmill/htm (accessed 02.06.2010) 66 Stork, J. & Teague, W.D. 1952. Flour for man’s bread. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. Tabor, R. 2008. Cadbury Castle, The Hillfort and landscape. The History Press, Stroud. Thomson, W.M. 1985 [1877]. The land and the book. Darf Publishers Limited, London. Thorpe, B. 1844. The homilies of the Anglo-Saxon Church. Vol. 1. The Aelfric Society, London. Tilley, C. 1999. Metaphor and material culture. Blackwell Publishers Ltd., Oxford. Tolley, C. 1994–1997. The mill in Norse and Finnish mythology. Saga-Book 24, 63–82. Vaughan Williams, R. & Lloyd, A.L. 1959. The Penguin Book of English folk songs. Penguin Books Ltd., Harmondsworth. Watts, M. 2002. The archaeology of mills & milling. Tempus Publishing Ltd., Stroud. Watts, S. 1999. An examination of the changes in the intensity of use of storage pits in the Iron Age. Unpublished individual study module, Certificate in archaeology, University of Exeter. Watts, S. 2011. The function of querns. In Williams, D. & Peacock, D. (eds.). Bread for the people: the archaeology of mills and milling. Proceedings of a colloquium held in the British School at Rome 4th–7th November 2009, pp. 341–348. University of Southampton, Series in Archaeology 3, British Archaeological Reports International Series 2274, Archaeopress, Oxford. Watts, S. 2012. Contexts of deposition. The structured deposition of querns in the south-west of England from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. Unpublished PhD thesis in archaeology, University of Exeter. Watts, S. 2014. The life and death of querns. Southampton momographs in archaeology new series 3, Highfield Press, Chandlers Ford. Wheeler, R.E.M. 1925. Prehistoric and Roman Wales. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Wikipedia 2012. Altweibermühle. http://de.,wikipedia.org (accessed 27.08.2012) Williams, D. & Peacock, D. (eds.) 2011. Bread for the people: the archaeology of mills and milling. Proceedings of a colloquium held in the British School at Rome 4th–7th November 2009. University of Southampton Series in Archaeology 3, British Archaeological Reports International Series 2274, Archaeopress, Oxford. Williams-Thorpe 1988. Provenancing and archaeology of Roman millstones from the Mediterranean area. Journal of Archaeological Science 15, 253–305. Worthen, S. 2006. Of mills and meaning. In Walton, S.A. (ed.). Wind & water in the Middle Ages, pp. 259–281. Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Tempe. Wright, M.E. 1988. Beehive quern manufacture in the southeast Pennines. Scottish Archaeological Review 5, 65–77. Young, D. 2006. The colours of things. In Tilley, C., Keane, W. & Küchler, S. (eds.). Handbook of material culture, pp. 173–186. Sage Publications, London.