Deconstructing the Hero

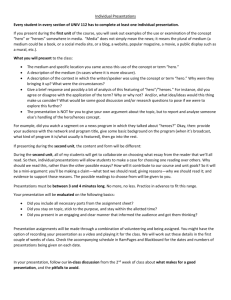

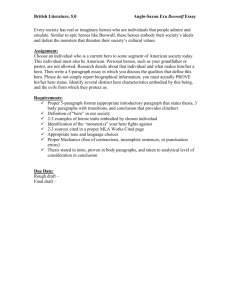

advertisement