Holy Spirit Seminary College of Theology and Philosophy

advertisement

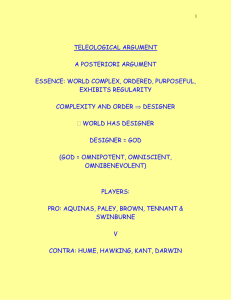

Holy Spirit Seminary College of Theology and Philosophy Aggregated to the Pontifical Urbaniana University Higher Institute of Religious Sciences Some Reflections on the “Anthropic Principle” of Fr. Tanzella-Nitti KWOK CHI KEUNG (I0908) HS102 Course Paper Moderator: Dr. Alex Mok Wing Kei HONG KONG February, 2010 “Anthropic Principle” was written by one of the chief editors of the Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science, Fr. Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti. A little background knowledge of the author would help us understand more of his stance. The information is a translation taken from his personal webpage.1 In the introduction, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti shows an appropriate attitude towards the relation between religion and science. Since Enlightenment, many atheists have rallied behind the Copernican Revolution to prove that Christianity is irrelevant to the modern world. The famous exchange between Napoleon and Laplace amply demonstrates such an attitude.2 In physical cosmology, the Earth has been dethroned from her central position in the universe. This is known as the Copernican Principle3. While many theologians would be alarmed by these secular challenges, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti, because of his trainings in astronomy and cosmology, treats the impact of Copernican Revolution as a change of perspective, forcing religion to rethink her ground instead of changing her beliefs. 1 He graduated in Astronomy at the University of Bologna (1977), a priest since 1987 and a Doctor of Theology (1991), is professor of fundamental theology at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome and visiting professor at the Faculty of Philosophy at the Pontifical University Gregorian. He has devoted himself for many years to scientific research in the field of radio astronomy and cosmology, by conducting its business as a researcher at the CNR Institute of Radio Astronomy in Bologna and then as an astronomer at the Astronomical Observatory of Turin. (from http://www.disf.org/tanzella-nitti/) 2 Someone had told Napoleon that the book contained no mention of the name of God; Napoleon, who was fond of putting embarrassing questions, received it with the remark, 'M. Laplace, they tell me you have written this large book on the system of the universe, and have never even mentioned its Creator.' Laplace, who, though the most supple of politicians, was as stiff as a martyr on every point of his philosophy, drew himself up and answered bluntly, 'Je n'avais pas besoin de cette hypothèse-là.' ("I had no need of that hypothesis.") Napoleon, greatly amused, told this reply to Lagrange, who exclaimed, 'Ah! c'est une belle hypothèse; ca explique beaucoup de choses.' ("Ah, it is a fine hypothesis; it explains many things.") (from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre-Simon_Laplace) 3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copernican_principle 1 This change of perspective had a major impact on theology, though more in its cultural and philosophical context than in its dogmatic content. Even in our days, the idea that science has finally demonstrated that the human being and its small host planet occupy a very minor role in the universe at large, is considered by many to have removed any theological illusion about the cosmic relevance of human life.4 Unexpectedly, experimental observations in the second half of the 20th century had opened the door to see a surge in the interest of experimental sciences to introduce the human elements in explaining the physical phenomena in the world and in engaging into dialogue with religion. From the second half of the 20th century, however, the set of observations and reflections known as “the Anthropic Principle” stand now as the first attempt, since the beginning of the Modern Age, to show that ascribing a more central role to humankind can unexpectedly result in a better scientific understanding of the universe, of its properties and evolution5. This essay will summarize the article Fr. Tanzella-Nitti published in INTERS and this author will give a few random thoughts on the relevance of the “Anthropic Principle” to faith. I. From the Copernican Principle to the Anthropic Principle First of all, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti summarized the historical development of worldviews since the Modern Age. At the pre-Modern Age, people embraced the Biblical worldview interpreted and explained by the Church. Man was the zenith (Genesis 1:26) as well as the 4 Anthropic Principle, INTERS – Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science, edited by G. Tanzella-Nitti, P. Larrey and A. Strumia, from http://www.disf.org/en/Voci/31.asp 5 op. cit. 2 centre (Genesis 2:18-20) of Creation. The Earth was stationary and heavenly bodies transversed across the filament. This was the Ptolemaic System of ancient Astronomy. The Earth occupied a central and privileged position in the cosmo. These phenomena were proclaiming the glory of the handiwork of God (Psalm 19:1). Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) found it more convenient to explain the apparent retrograde motion of the planets by giving up the central position of the Earth. Instead, choosing the sun as the centre and making the Earth circling around the sun explained the observations better. Since 1850, people have called this worldview, viz. that the Earth is not a central, specially favoured position, the Copernican Principle 6 . Following suits, scientific method itself began to emphasize the Principle of Covariance which requires that the laws of nature and the principles of the experimental sciences must be formulated with those physical quantities the measurements of which the observers in different frames of reference could unambiguously correlate7. Science was then concerned with refining more and more the formulation of protocols to regulate an ever more objective and impersonal knowledge 8 . Modern physical cosmology extends these two principles above to formulate the “Cosmological Principle” which states that, viewed in a sufficiently large scale, the properties of the Universe are the same for all observers 9. In short, the Universe is the same whether there is or is not any human observer. The presence of humankind plays no role in the Universe and its evolution. 6 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copernican_principle 7 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principle_of_covariance 8 INTERS, ibid. 9 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmological_principle 3 The tide began to turn. When some scientists began to reflect on the fundamental physical parameters which determined the structure and the physical-chemical laws of the Universe and its evolution, these parameters have been precisely also those parameters necessary to host life and intelligent observers. What was more, these conditions were present during the early moments of the “Big Bang”. Back in 1937, Dirac had pointed out some interesting numerical coincidences existing between the relevant values of the global properties of the Universe. In 1961, Dicke stressed that the presence of life strongly conditioned the value assumed by some cosmological “observed” magnitudes. In 1974, Carter presented the Anthropic Principle in a coherent manner, stressing human as an observer and the legitimacy of formulating this principle for its capacity of predictability. Carter formulated a Weak Anthropic Principle (WAP) and a Strong Anthropic Principle (SAP). WAP: the values of some specific cosmological parameters can only be those that are compatible with the existence of observers in the Universe. SAP: the Universe must possess only those properties and parameters which determine, in some stage of its development, the birth and then the presence of observers. In 1986, Barrow & Tipler published the influential The Anthropic Cosmological Principle in which they formulated four variants of the Anthropic Principle. WAP: the observed values of all physical and cosmological quantities are not equally probable but they take on values restricted by the requirement that there exist sites where carbon-based life can evolve and by the requirement that the Universe be old enough for it to have already done so. SAP: The Universe must have those properties which allow life to develop within it 4 at some stage in its history. Participatory Anthropic Principle (PAP): Observers are necessary to bring the Universe into being. Final Anthropic Principle (FAP): Intelligent information-processing must come into existence in the Universe, and once it comes into existence, it will never die out. The stage is now set to consider the basis of the Anthropic Principle. II. The Scientific Observations at the basis of the Anthropic Principle Scientists have noticed the delicacy of the values of the four physical constants which regulate the intensity of the interaction of the four fundamental forces which in turn determine the structuring of the cosmos. For example, The ratio between the number of protons and neutrons was frozen at about one second after the Big Bang. This ratio depends on the gravitational constant ag and the intensity of the weak interaction, thus the weak interaction constant aw. If ag/aw had been lightly bigger, all hydrogen would have become helium. No water would have formed. Had it been lightly smaller, no cosmological helium would have formed, causing stars to evolve so rapidly that no life would eventually develop on the planets. The strong force constant as and electromagnetic constant a play an important role for the development of a chemistry adequate for life. Had a been a little bigger or as a little smaller, no nuclei would have been stable. Interstellar gas clouds contract due to gravity. They heat up in the contraction process. If a threshold temperature were not reached in time, the universe would be full of failed stars without planets and life. Such a threshold temperature depends on the delicate relationship between ag and 5 the other physical constants. Biological molecules are built from heavy chemical molecules produced in the nuclei of stars. Some ways have to be found to eject these heavy elements from the nuclei of stars to the interstellar space. That is to say, a significant number of stars must die as supernovae. This phenomenon is determined by the values of ag and aw. These physical constants were fixed within 10-6 second after the Big Bang. They determined the critical sequence of phenomena that led to the existence of a physics and a chemistry necessary for life. In short, the essential characteristics of our universe appear finely tuned for life. III. The Interpretation of Scientific Data and the Most Significant Philosophical KeyPoints Fr. Tanzella-Nitti then turns to clarify some philosophical implications behind the Anthropic Principle. 1. The Distinction between WAP and SAP. WAP asserts that the conditions and the observed coincidences are necessary but not sufficient conditions for the appearance of life, while SAP states that they are both necessary and sufficient. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti judges that SAP cannot be founded on the scientific level simply because we do not know all the conditions and processes in the cosmos. WAP is not anthropic. It deals with conditions necessary for an organic, carbonbased chemistry and an adequate biology. In contrast, SAP includes an intelligent observer in the universe. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti thinks that the scientific data do not warrant such an absolute claim. 6 2. Objections to the Anthropic Principle b) The supposed tautological value of the Principle Fr. Tanzella-Nitti agrees with this objection but points out that this objection does not remove all of the Principle's significance. He quoted the tautological statement “the sky at night is dark” and explained it with the expansion of the universe, the redshift of lights coming from distant stars etc. to illustrate the significance of this tautological statement. In the same way, the many relations that the fine tuning expresses add a new knowledge to physics and to the properties of the cosmos. Unfortunately, Fr. Tanzella- Nitti fails to substantiate such a claim other than a vague statement that the universe is much more “one” and coherent in itself than previously expected. c) The existence of a more fundamental general law of the nature Fr. Tanzella-Nitti dismissed this objection because such an allencompassing explanation for the whole of existence, including the problem of the whole and the problem of origin, is metaphysical in nature and no longer belongs to the domain of natural sciences. d) Using many-universe models to explain the fine tuning There are many universes and we, intelligent observes, happen to exist in the fine tuned one. This explanation is of no value because it is nonfalsifiable. Another solution is to hypothesize that our universe has gone through many previous Big Bangs and Big Crunches until it reaches the present fine tuned state. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti argued that observations seem to indicate that our universe is open, i.e. there is no sign of a Big Crunch. Furthermore, the number of possible “cycles” has an upper limit. 7 Unfortunately, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti did not support these two claims with scientific evidence. He also rejected the quantum cosmology model for being experimentally non-falsifiable. All these multi-universe models violate the “Ockham's Razor”. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti concluded that all these objections appeal to some a priori philosophical arguments which exceed the domain of scientific data. 1. The True Scientific Significance of the Anthropic Principle Fr. Tanzella-Nitti then put forth his opinion on the most relevant, non-tautological contents of what Anthropic Principle implies. a) The evolution of the universe strongly manifests a character of unity and coherence. b) Biology and human life strongly depends upon the whole history of the universe and in this history, nothing seems to be superfluous. There exists only that which is strictly necessary for hosting life. c) The necessary conditions that render life possible present themselves as “original, or primeval conditions”. They are non-evolutionary. The paradigm of natural selection and the capacity for adaption to the environment cannot be the only criteria to have operated in the long chain of events that accompanied the evolution of life. 8 IV. The Anthropic Principle between Science and Religion: is there any Design in the Cosmo? Fr. Tanzella-Nitti then turns to the use of Anthropic Principle in the Argument from Design and explores the legitimacy of such a use. 1. Anthropic Principle and the “Argument from Design” For centuries, Christians have made use of the presence of an intelligent design as a proof for the existence of the Creator God. In philosophy, St. Thomas Aquinas argued from the recognition of the finality of nature to arrive at the existence of God. This is known as his “fifth way”. The English Anglican apologetics of the 17th and 18th centuries argued from scientific observations, much like what some people do with the Anthropic Principle today. Criticism of this argument from Design came from Hume and Kant in philosophy and Charles Darwin in natural sciences. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti argues that the notion of design refers to the presence of intentionality and intelligence. But one cannot employ the Anthropic Principle as the proof of intelligent design; nor can it demonstrate the existence of a necessary and absolute intentionality which drives the universe towards the appearance of life and human beings. 2. The Peculiarity of the Anthropic Principle among the Various Arguments from Design. Though one cannot use the Anthropic Principle directly as a proof of intelligent design, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti recognized in the peculiarities of the Principle its ability to join together the three components of design: coherence, teleologism and reference to a mind. a) The fine-tuning of the constants of nature is not the result of an adaptation to the environment or of natural selection. They have been coherent from start. 9 b) The Anthropic Principle is a global and all-encompassing teleological proposal, intended to show the functioning of a finalistic principle from the era of Planck (10-33 second from the Big Bang) up until our days. c) The Argument from Design associated with the SAP points to a “mind”. 3. Anthropic Principle and the Christian Theology of Creation. The Christian universe is the intentional effect of a personal Word, intelligible and open to dialogue. It develops through time, not driven by blind chance, but according to a rationality which stems from an original simplicity, that has in God its first and its final causality. The biotic conditions expressed by the Anthropic Principle are consistent with what the theology of creation says, though the knowledge brought about by the Principle cannot provide any logical-demonstrative proof for the contents of theology, nor can it be any “scientific” refutation of the existence of a Creator. The Principle provides the scientific researchers with elements of reflection on the ultimate why's of reality, on the mystery of being. V. Anthropic Principle and Theological Christocentrism 1. Unity and Coherence of the Cosmos under a Christocentric Perspective In Christian theology, the Incarnation of the Son of God is the most important principle of coherence and unity of all that is created. Christ is the head not only because the Creation was done through him and in him, but also because his death and resurrection is the completion of the expectation of the whole creation and the beginning of a new creation. Fr. Tanzella-Nitti asked whether the centrality of life and the special role of intelligent observers, as they are stated by the Anthropic Principle, might contain some points of connection with a theological anthropology finding its completion in Christology. 10 Fr. Tanzella-Nitti went through the works of Duns Scotus and the philosophical thinking of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who reads the biological and cosmological evolution --- of matter to life, of life to man and of man to Christ --- as a grandiose ascending process that realizes the definitive headship of Christ over all things. His ideas must have inspired scientists who subscribe to the Anthropic Principle, especially on FAP. However, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti went on to criticize de Chardin for underestimating the mediation that Christ exercised in the beginning and did not offer a complete understanding of the relationship of continuity / discontinuity between the first and the new creation. 2. The Paradox of the Cosmos and the Mystery of the Risen Christ. The Anthropic Principle could not demonstrate that the appearance of human being fulfils an immanent and unavoidable cosmic law; thus the necessity of the Incarnation of the Word-Logos. The latter belongs to they mystery of the God-Father, a personal intentionality that remains non-accessible to scientific data, or to any philosophical use of an SAP. As for the eschatological implications of contemporary cosmology, Fr. TanzellaNitti believes that theological Christocentrism beings its specific contribution to the new vision of the cosmos provided by Anthropic Principle. Anthropic Principle ends up in an apparent paradox. The universe with finely tuned parameters necessary for life is a universe in which “the window of opportunity” for the sustenance for life and of human beings remains extraordinarily small. It is a very short time-span when compared to the whole history of the cosmos. Why then does the universe contain the keys for an opportunity that would be destined to terminate quite soon? Would something serve these fragile equilibria if life is destined to be extinguished so soon? 11 Here, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti optimistically sought help from Christology. A universe created through Christ would be destined to be transfigured like the body of the risen Christ. In a Christocentric universe, life and matter are destined to be transfigured like the body of the risen Christ10. The existence of a narrow window of opportunity for life no longer appears contradictory. This is a response that faith, not science, can offer to the paradox. Unfortunately, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti did not elaborate. He simply said that it is a contradiction that can be healed by Christ. VI. Some Reflections on Fr. Tanzella-Nitti's article As I have complained before in various places, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti had not elaborated on several scientific points. He did not illustrate the predictive power of the Anthropic Principle (I). Taking a look at the “Application of the Principle” section of the “Anthropic Principle”11 entry in Wikipedia will show us how the Principle predicted the existence of an as yet undiscovered Carbon-12 resonance. He did not provide the readers with scientific citations proving the openness of the present universe, or the upper limit of the number of allowable cyclical Big Bangs and Big Crunches (III 2). He did not substantiate how one and coherent the universe had been (III 3). Perhaps he had to take into considerations the limitations of web publishing and copyright issues etc. We cannot blame him too much. In discussing the objections to the Anthropic Principle (III 2), Fr. Tanzella-Nitti limited himself to only three categories of objections. Are there any other objections that do not fall into these three categories? For one, Sharpe & Walgate (2002) attacked the Anthropic Principle on philosophical ground. They objected to reading purpose into reality. 10 INTERS, ibid. 11 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropic_principle 12 It was crude philosophizing. Rather, scientists should look at the physical details of the problem12. Ken Olum (2004) looked at galaxy-wide civilizations. At present, we do not belong to any huge civilization in the universe. We have not yet been able to establish contact with any ET. The Anthropic Principle predicts that we are a typical civilization in the universe. Furthermore, he derives that large civilizations are the dominant ones in the universe. But we do not belong to them. Therefore, either the Anthropic Principle is wrong, or the we have not understood properly the structure of the universe and its processes. Anthropic reasoning predicts that we are typical, and thus it predicts with great confidence that we belong to a large civilization … it appears that the very largest civilizations are likely to be the dominant ones13. More and more people are applying probabilistic reasoning to approach the issue. Trotta and Starkman (2006) is one such example. They took the cosmological constant energy density and analyzed its variations. They were attempting to frame an anthropic reasoning in probabilistic terms. Since there is no privileged weighting on the parameters, anthropic reasoning fails to explain the value of 14 . These examples show that the debate on the Anthropic Principle lives on and spills over the three categories Fr. Tanzella-Nitti outlined. We have only one universe to make observations. So, everything seems to have been fixed and we are not able to detect alternative values of those primeval constants. However, has anyone cast doubt on the Principle of Covariance or even the Cosmological Principle? Are they not just working principles, subject to modifications in the light of new 12 Kevin Sharpe & Jonathan Walgate, “The Anthropic Principle: Life in the Universe”, Zygon vol 37 no.4 (December 2002), pp 925-939 13 Olum, K.D., “Conflict between anthropic reasoning and observation”, Analysis 64.1, January 2004, pg.2 14 Trotta, R. & Starkman, G.D., “What's the trouble with anthropic reasoning?”, CP878, The Dark Side of the Universe, DSU 2006, American Institute of Physics, pp. 323-329 13 physical data yet to be discovered? We have not yet scanned every cubic light-year of the cosmos. Is it possible for those primeval constants to acquire different values in different regions of the universe? Haven't scientists been talking about Dark Matter which might have different properties? I even cast doubt on the reasoning of the Big Bang. From the observation of an expanding universe, scientists pushed time all the way back to the “beginning”. What made them so confident that they can push time all the way back to t=0? Would it not be possible that time began not at zero, but at t=N, where N is a positive number? In other words, a stable universe had existed for a certain duration and for some physical reasons to be discovered, began its present day expansion? I am proposing a 「盤 古」model. If you ask me how the stable universe came about, well, a baby universe probably had evolved, experimenting with different values of primeval constants until it reached stability. Metaphysical fantasy! Let me return to Fr. Tanzella-Nitti. On his final point about the paradox created by the Anthropic Principle, Fr. Tanzella-Nitti remains tentative and cautious. He simply dropped a hint that a Christocentric universe would be transfigured just as Christ's risen body. Period. He was reticent and refused to speculate how the universe would be transformed after the Last Judgment. Perhaps he was bound by the official eschatology of the Church. He was not allowed to speculate too far off. VII. Conclusion There are different modes of truth, scientific, philosophical and religious. Christian faith is based on the salvific truth revealed in Christ. It does not contradict scientific truths. On the contrary, scientific truths can shed light on the reasonableness of Christian faith. The Anthropic Principle is a welcomed attempt to open up the dialogue between religion and science. In return, the revealed truth of God should prod open-minded scientists to search for the ultimate meaning of human life on Earth. 14

![Student Resource Sheet 3[LA]: Anthropic Arguments](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007328335_1-62024b5821d7739ef5907c8f45a8dd1d-300x300.png)