Knowledge-based marketing

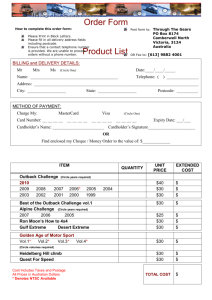

advertisement