A Path to Good Corrections - Northern Territory Government

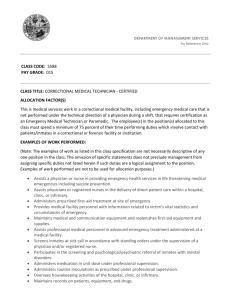

advertisement