Plagiarism - University of Kent

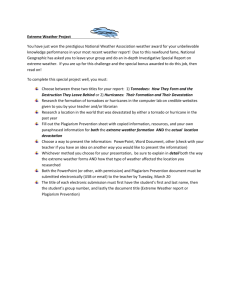

advertisement