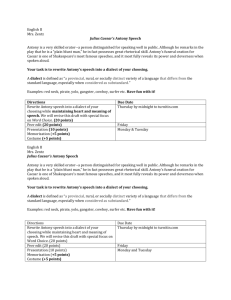

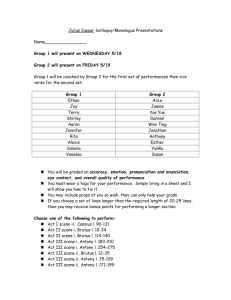

Hansen-Master - DUO

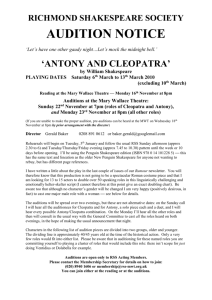

advertisement