Strategy

T. Kretschmer

MN3119

2013

Undergraduate study in

Economics, Management,

Finance and the Social Sciences

This is an extract from a subject guide for an undergraduate course offered as part of the

University of London International Programmes in Economics, Management, Finance and

the Social Sciences. Materials for these programmes are developed by academics at the

London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

For more information, see: www.londoninternational.ac.uk

This guide was prepared for the University of London International Programmes by:

T. Kretschmer, Professor of Business Studies, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich,

Germany.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Brooke Russell for her excellent assistance on the first

edition of the guide and especially her help with the extended activities. Thorsten Grohsjean,

Christina Finsterwalder and Sanja Rikanovic were very helpful in the revision of this guide,

in particular in putting together the guide to the in-chapter activities and the sample

examination questions.

This is one of a series of subject guides published by the University. We regret that due to

pressure of work the author is unable to enter into any correspondence relating to, or arising

from, the guide. If you have any comments on this subject guide, favourable or unfavourable,

please use the form at the back of this guide.

University of London International Programmes

Publications Office

University of London

Stewart House

32 Russell Square

London WC1B 5DN

United Kingdom

www.londoninternational.ac.uk

Published by: University of London

© University of London 2013

The University of London asserts copyright over all material in this subject guide except where

otherwise indicated. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form,

or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. We make every effort to

respect copyright. If you think we have inadvertently used your copyright material, please let

us know.

Contents

Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction........................................................................................... 1

1.1 Introduction to the subject........................................................................................ 1

1.2 Aims of this course................................................................................................... 1

1.3 Learning outcomes................................................................................................... 1

1.4 The structure of the course........................................................................................ 1

1.5 Use of the guide and hours of study.......................................................................... 2

1.6 Essential reading...................................................................................................... 2

1.7 Further reading......................................................................................................... 3

1.8 Online study resources.............................................................................................. 5

1.9 The examination and examination advice.................................................................. 6

1.10 The syllabus............................................................................................................ 7

Chapter 2: The evolution of strategic management as an interdisciplinary field... 9

Learning outcomes......................................................................................................... 9

Essential reading............................................................................................................ 9

2.1 Introduction............................................................................................................. 9

2.2 Early theories .......................................................................................................... 9

2.3 Michael Porter and the industrial organisation paradigm......................................... 10

2.4 Organisational economics....................................................................................... 10

2.5 Resource-based view, dynamic capabilities and leadership theory ........................... 11

2.6 A consensus definition of the field........................................................................... 11

2.7 Key concepts ......................................................................................................... 12

2.8 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 12

Chapter 3: Analysis of market structure................................................................ 13

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 13

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 13

Further reading............................................................................................................. 13

3.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 13

3.2 Techniques of market definition............................................................................... 13

3.3 Market analysis with many firms............................................................................. 16

3.4 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 18

3.5 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 18

3.6 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 18

Extended activity: the commercial banking industry in the United States........................ 19

Chapter 4: Introduction to game theory and strategy.......................................... 21

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 21

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 21

Further reading............................................................................................................. 21

4.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 21

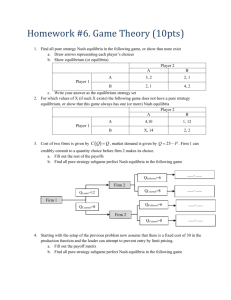

4.2 Static games........................................................................................................... 22

4.3 Dynamic games...................................................................................................... 27

4.4 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 30

4.5 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 30

4.6 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 30

i

MN3119 Strategy

Chapter 5: Oligopolistic models of competition................................................... 33

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 33

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 33

Further reading............................................................................................................. 33

5.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 33

5.2 Preliminaries.......................................................................................................... 34

5.3 Bertrand competition.............................................................................................. 34

5.4 Cournot competition............................................................................................... 35

5.5 Comparing Bertrand and Cournot........................................................................... 36

5.6 Stackelberg leadership............................................................................................ 37

5.7 Product differentiation............................................................................................ 38

5.8 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 39

5.9 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 39

5.10 Sample examination questions.............................................................................. 39

Extended activity: articles on Airbus-Boeing competition ............................................... 40

Chapter 6: The resource-based view of the firm .................................................. 41

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 41

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 41

Further reading............................................................................................................. 41

6.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 41

6.2 Competitive advantages and resources................................................................... 42

6.3 Some examples of resources as sources of competitive advantage........................... 43

6.4 The dynamics of resource and capability building..................................................... 46

6.5 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 47

6.6 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 48

6.7 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 48

Extended activity: Dell Computer Corporation ............................................................... 48

Chapter 7: Strategic asymmetries – persistent dominance over time.................. 69

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 69

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 69

Further reading............................................................................................................. 69

7.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 69

7.2 Firm asymmetries – long- or short-term?................................................................. 69

7.3 Traditional sources of persistent dominance............................................................. 71

7.4 Dynamic capabilities............................................................................................... 75

7.5 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 76

7.6 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 76

7.7 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 76

Extended activity: competition in the wide-body aircraft market..................................... 76

Chapter 8: Organisation design............................................................................. 77

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 77

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 77

Further reading............................................................................................................. 77

8.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 77

8.2 Strategy and structure............................................................................................ 77

8.3 Organisation design and competitive advantage..................................................... 83

8.4 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 83

8.5 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 83

8.6 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 84

ii

Contents

Chapter 9: Value chain analysis: vertical relations................................................ 85

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 85

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 85

Further reading............................................................................................................. 85

9.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 85

9.2 Double marginalisation........................................................................................... 85

9.3 Vertical foreclosure................................................................................................. 88

9.4 Key concepts.......................................................................................................... 89

9.5 A reminder of your learning outcomes..................................................................... 90

9.6 Sample examination questions................................................................................ 90

Extended activity: outsourcing at Eriksson and Sony and Loews..................................... 90

Chapter 10: Vertical integration and transaction cost.......................................... 91

Learning outcomes....................................................................................................... 91

Essential reading.......................................................................................................... 91

Further reading............................................................................................................. 91

10.1 Introduction......................................................................................................... 91

10.2 Purchasing versus production costs....................................................................... 91

10.3 Coordination costs............................................................................................... 92

10.4 Proprietary knowledge.......................................................................................... 93

10.5 Transaction costs.................................................................................................. 94

10.6 Asset specificity.................................................................................................... 95

10.7 Alternatives to ‘make’ or ‘buy’............................................................................... 96

10.8 Key concepts........................................................................................................ 97

10.9 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................... 97

10.10 Questions for discussion..................................................................................... 97

Extended activity: athenahealth.................................................................................... 97

Chapter 11: Collusion.......................................................................................... 103

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 103

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 103

Further reading........................................................................................................... 103

11.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 103

11.2 Stability of cooperation....................................................................................... 103

11.3 Extending the model........................................................................................... 105

11.4 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 107

11.5 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 107

11.6 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 107

11.6 Extended activity: the DeBeers diamond cartel.................................................... 107

Chapter 12: Strategic partnerships..................................................................... 115

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 115

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 115

Further reading........................................................................................................... 115

12.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 115

12.2 Building capabilities........................................................................................... 115

12.3 Business and strategic partnerships..................................................................... 116

12.4 Equity ownership................................................................................................ 118

12.5 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 120

12.6 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 120

12.7 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 120

Extended activity: the EU aviation industry.................................................................. 120

iii

MN3119 Strategy

Chapter 13: Competitive dynamics..................................................................... 123

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 123

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 123

Further reading........................................................................................................... 123

13.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 123

13.2 A framework to analyse competitive dynamics..................................................... 124

13.3 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 127

13.4 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 127

13.5 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 127

Chapter 14: Entry and entry deterrence.............................................................. 129

Learning outcome....................................................................................................... 129

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 129

Further reading........................................................................................................... 129

14.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 129

14.2 Structural entry barriers...................................................................................... 130

14.3 Strategic entry barriers........................................................................................ 132

14.4 Summary............................................................................................................ 136

14.5 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 136

14.6 A reminder of your learning outcome.................................................................. 137

14.7 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 137

Extended activity: Dubai flowers and internet banking................................................. 137

Chapter 15: Research and development competition......................................... 143

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 143

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 143

Further reading........................................................................................................... 143

15.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 143

15.2 Terminology........................................................................................................ 143

15.3 Innovation and market structure......................................................................... 146

15.4 Strategic issues in R&D....................................................................................... 151

15.5 Some further thoughts on R&D........................................................................... 155

15.6 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 156

15.7 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 156

15.8 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 157

Extended activity: discovering DNA............................................................................. 158

Chapter 16: Technology adoption........................................................................ 169

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 169

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 169

Further reading........................................................................................................... 169

16.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 169

16.2 Adoption dependence......................................................................................... 169

16.3 Strategic technology adoption – option value...................................................... 170

16.4 Technology diffusion models............................................................................... 172

16.5 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 176

16.6 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 176

16.7 Sample examination questions............................................................................ 176

Extended activity: the adoption of Botox..................................................................... 177

Chapter 17: Network effects............................................................................... 181

Learning outcomes..................................................................................................... 181

Essential reading........................................................................................................ 181

Further reading........................................................................................................... 181

iv

Contents

17.1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 181

17.2 Network market structures.................................................................................. 182

17.3 Technology diffusion with network effects........................................................... 183

17.4 Generic strategies in network markets................................................................. 186

17.5 Fighting a standards battle................................................................................. 187

17.6 Key concepts...................................................................................................... 188

17.7 A reminder of your learning outcomes................................................................. 188

17.8 Questions for discussion..................................................................................... 188

Extended activity: Skype and digital cinema................................................................. 188

Appendix 1: Sample examination paper............................................................. 191

Appendix 2: Guidance on answering the Sample examination paper................ 193

v

MN3119 Strategy

Notes

vi

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Introduction to the subject

Let us begin this course with a wager: I bet you that, when opening

the business section of your local newspaper, you will find the word

‘strategy’ at least once per page. A Google search of ‘strategy’ throws up

1,010,000,000 hits. Narrowing this down to ‘business strategy’ leaves

us with 622,000,000 hits. That’s a lot of business strategy! There are a

large number of definitions of strategy, and I will not attempt to write my

own. There are also entire research fields of ‘business strategy’ ‘corporate

strategy’ ‘strategy content’ ‘strategy process’ ‘management strategy’

‘competitive strategy’ and so on, and I will not get into the fine distinctions

between one and the other. Much more, I will try to boil down ‘strategy’

to what most definitions have in common, and more importantly, I will

introduce a number of techniques that will be helpful in formulating,

analysing and implementing a strategy.

1.2 Aims of this course

In this course, you will not learn ‘how-to’ recipes of how to react to specific

situations. What you will learn is a way of thinking about such situations.

In management, as in economics, the right answer to almost any question

is ‘it depends’. What you will learn in this course is what the right answer

depends on and, given a particular set of circumstances, how you can

analyse the situation.

1.3 Learning outcomes

Once you have completed the course and done the Essential reading and

activities, you should be able to:

• use tools of strategic analysis and game theory to value and analyse

strategic options in real life.

In particular, you should be able to:

• anticipate the actions of a rational (that is, individually profitmaximising) rival and act accordingly.

1.4 The structure of the course

The course is structured in six parts: after this and the following

introductory chapter, the basic building blocks of strategic analysis are

introduced: market analysis, game theory and oligopoly competition. We

will refer back to these chapters often in later chapters, so you are advised

to spend a significant amount of time on these and make sure you have

understood the basic principles and techniques of these chapters. The

third part introduces the sources of competitive advantage – resources and

capabilities, strategic asymmetries and organisation design. These chapters

will aim to explain why firms are different, in what way and what makes

some firms more successful than others. The fourth part will study firms

and their relations to other firms. Why are some firms vertically integrated

and some not, and what are the implications of this? When do firms

cooperate with rivals, and what do partnerships among firms typically look

like? The fifth part takes a closer look at competition among firms – over

1

MN3119 Strategy

time, and in specific situations like entry or research and development.

This is where we will use the tools of game theory we introduced in the

second part of the guide very intensively. In the final part we will look at

some of the particularities of high-technology industries. This part of the

guide may be considerably more demanding technically than the previous

ones, but by then you should have had enough opportunity to study, revise

and practise the concepts from previous chapters. See this final part as the

‘icing on the cake’ – after you have looked at many techniques and topics

in isolation, these last chapters give you an opportunity to look at some of

them in combination.

1.5 Use of the guide and hours of study

To help you get the most out of this course, you will be given a number

of examples and activities throughout each chapter. These will vary in

difficulty and style. When you read a chapter, try and do these as you go

along, and go back to the ones you had problems with the first time round

once you have completed the chapter.

At the end of the chapter, you will find a list of questions or exercises

designed to challenge you and to check if you have read and understood

the chapter. They are titled Sample examination questions. These precise

questions are unlikely to come up, but they should give you a general

impression of the level that is required in this course. If you are studying

this text in a group, you might want to consider discussing these questions

in a tutorial-style session at the end of each chapter.

As a further test of your skills, most chapters will have an Extended

activity in a separate section. This is a longer text, case study, interview,

quote etc. that illustrates some of the concepts in the chapter, and gives

some concrete questions at the end. These activities will test your overall

grasp of the chapter and are often not limited to one chapter or one topic.

The advice normally given to International Programmes students is that

if they are studying one course a year, they should allow at least six hours

of study every week. Most of the chapters are relatively short compared to

regular textbook chapters. Therefore, a chapter should be read all in one

go to give you a general idea of what it is about. After that, you should set

some time aside to work through the chapter properly. Times will vary for

every student and every chapter.

Sample examination questions and extended activities will probably

take very little time if you just glance over them and sketch them out in

your mind. It is recommended, however, that you write out some of your

answers as you may find that a casual thought will not look as convincing

if you write them out on paper and you need to have a clear, coherent and

logical argument.

1.6 Essential reading

For many chapters, the Essential reading is:

Cabral, L.M.B. Introduction to Industrial Organization. (Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 2000) [ISBN 9780262032865].

The chapters in the book will often clarify points and go a little further,

but you will find most of the points covered in the subject guide chapters

are also covered in Cabral. Reading further often highlights some specific

aspects of the chapters or describes some of the research findings

explained in the chapter. If you would like to get another perspective on

2

Chapter 1: Introduction

strategy from an economics viewpoint, you should have a look at

Besanko, D., D. Dranove, M. Shanley and S. Shaefer Economics of Strategy.

(New Jersey: Wiley, 2009) fifth edition [ISBN 9780470484838].

or

Saloner, G., A. Shepard and J. Podolny Strategic Management. (New Jersey:

Wiley, 2006) revised edition [ISBN 9780470009475].

Detailed reading references in this subject guide refer to the editions of the

set textbooks listed above. New editions of one or more of these textbooks

may have been published by the time you study this course. You can use

a more recent edition of any of the books; use the detailed chapter and

section headings and the index to identify relevant readings. Also check

the virtual learning environment (VLE) regularly for updated guidance on

readings.

Journals

Dierickx, I. and K. Cool ‘Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of

competitive advantage’, Management Science 35(12) 1989,

pp.1504–511.

Dyer, J. and H. Singh ‘The relational view: co-operative strategy and sources of

interorganisational competitive advantage’, Academy of Management Review

23(4) 1998, pp.660–79.

Haskel, J. and C. Martin ‘Capacity and competition: empirical evidence on UK

panel data’, Journal of Industrial Economics 42(1) 1994, pp.23–44.

Lexecon Ltd ‘An introduction to quantitative techniques in competition

analysis’, Lexecon Ltd. publication, mimeo. www.crai.com/ecp/assets/

quantitative_techniques.pdf

Swaminathan, A. ‘Entry into new market segments in mature industries:

endogenous and exogenous segmentation in the US brewing industry’,

Strategic Management Journal 19(4) 1998, pp.389–404.

1.7 Further reading

Please note that as long as you read the Essential reading you are then free

to read around the subject area in any text, paper or online resource. You

will need to support your learning by reading as widely as possible and by

thinking about how these principles apply in the real world. To help you

read extensively, you have free access to the VLE and University of London

Online Library (see below).

For your ease of reference here is a list of all the Further reading for this

course.

Angelmar, R. ‘Market structure and research intensity in high-technologicalopportunity industries’, Journal of Industrial Economics 34(1) 1985,

pp.69–79.

Arora, Alfonso Gambardella ‘Complementarities and external linkages: the

strategies of large firms in biotechnology’, Journal of Industrial Economics

38(4) 1990, pp.361–79.

Barney, J.B. ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’, Journal of

Management 17 1991, pp.99–120.

Barney, J.B. ‘Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A tenyear retrospective on the resource-based view’, Journal of Management

6(2001a), pp.643–50.

Benkard, L. ‘Learning and forgetting: the dynamics of aircraft production’,

American Economic Review 90(4) 2000, pp.1034–54.

Bryson, A., R. Gomez and T. Kretschmer Catching a wave: the adoption of

voice and high-commitment workplace practices in Britain, 1984–1998. CEP

3

MN3119 Strategy

discussion paper DP 0676. (London: Centre for Economic Performance,

2005) (http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/).

Cabral, L. ‘R&D competition when firms choose variance’, Journal of Economics

and Management Strategy 12(1) 2003, pp.139–50.

Cabral, L. and M. Riordan ‘The learning curve, predation, antitrust, and

welfare’, Journal of Industrial Economics 45(2) 1997, pp.155–69.

Camerer, C. ‘Redirecting research in business policy and strategy’, Strategic

Management Journal 6(1) 1985, pp.1–15.

Chen, M.-J. ‘Competitor analysis and interfirm rivalry: towards a theoretical

integration’, Academy of Management Review 21(1) 1996, pp.100–34.

Chen, M.-J. and D. Miller ‘Competitive dynamics: themes, trends, and a

prospective research platform’, The Academy of Management Annals 6(1)

2012, pp.135–210.

Church, J. and R. Ware Industrial Organisation: A Strategic Approach. (New

York: McGraw-Hill, 2000) [ISBN 9780071166454] Chapter 8, Classic

Models of Oligopoly

Csaszar, F. ‘Organizational structure as a determinant of performance: evidence

from mutual funds’, Strategic Management Journal 33 2012, pp.611–32.

David, P. ‘Clio and the economics of QWERTY’, American Economic Review 75(2)

1985, pp.332–37.

Dixit, A. and S. Skeath Games of strategy. (London: Norton & Company, 2004)

second edition [ISBN 9780393924992].

Emmons, W. and R. Prager ‘The effects of market structure and ownership

on prices and service offerings in the US cable television industry’, Rand

Journal of Economics 28(4) 1997, pp.732–50.

Farrell, J. and G. Saloner ‘Standardization, compatibility, and innovation’, Rand

Journal of Economics 16(1) 1985, pp.70–83.

Ferrier, W.J., K.G. Smith and C.M. Grimm ‘The role of competitive action in

market share erosion and industry dynamics: a study of industry leaders

and challengers’, Academy of Management Journal 42(4) 1999, pp.372–88.

Fudenberg, D. and J. Tirole ‘Preemption and rent equalization in the adoption

of new technology’, Review of Economic Studies 52(3) 1985, pp.383–402.

Geroski, P. ‘Early warning of new rivals’, Sloan Management Review 40(3) 1999,

pp.107–16.

Geroski, P. ‘Models of technology diffusion’, Research Policy 29(4–5) 2000,

pp.603–25.

Geroski, P. ‘Thinking creatively about markets’, International Journal of

Industrial Organisation 16(6) 1998, pp.677–95.

Gilbert, R. and D. Newbery ‘Preemptive patenting and the persistence of

monopoly’, American Economic Review 72(3) 1982, pp.514–26.

Griliches, Z. ‘Hybrid corn: an exploration in the economics of technological

change’, Econometrica 1957. Reprinted in Z. Griliches (ed.) Technology,

Education, and Productivity. (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1988) [ISBN

9780631156147] pp.27–52.

Hamel, G. and C.K. Prahalad ‘The core competence of the corporation’, Harvard

Business Review 68(May–June) 1990, pp.79–93.

Hitt, M., H.I.R. Volberda, R. Morgan, R. Hoskisson and P. Reinmoeller Strategic

Management: Competitiveness and Globalization. (Hampshire: Cengage

Learning EMEA, 2011) [ISBN 9781408019184].

Katz, M. and C. Shapiro ‘Systems competition and network effects’, Journal of

Economic Perspectives 8(2) 1994, pp.93–115.

Kay, J. Foundations of Corporate Success: How Business Strategies Add Value. (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1995) [ISBN 9780198289883] Chapters 5–8.

Klette, T. ‘R&D, scope economics, and plant performance’, Rand Journal of

Economics 27(3) 1996, pp.502–22.

Koski, H and T. Kretschmer ‘Survey on competing in network industries: firm

strategies, market outcomes and policy implications’, Journal of Industry,

Competition and Trade 4(1) 2004, pp.5–31.

4

Chapter 1: Introduction

Kretschmer, T. and P. Puranam ‘Integration through incentives within

differentiated organisations’, Organization Science 19(6) 2008, pp.860–75.

Leonard, R. ‘Reading Cournot, reading Nash’ Economic Journal 104(424) 1994.

Lieberman, M. ‘Market growth, economies of scale, and plant size in the

chemical processing industries’ Journal of Industrial Economics 36(2) 1987,

pp.175–91.

McAfee, P., H. Mialon and M. Williams ‘What is a barrier to entry?’, American

Economic Review Papers and Proceedings (94) 2004, pp.461–65.

Monteverde, K. ‘Technical dialog as an incentive for vertical integration in the

semiconductor industry’, Management Science 41(10) 1995, pp.1624–38.

Ohashi, H. ‘The role of network effects in the US VCR market, 1978–86’,

Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 12(4) 2003, pp.447–94.

Peteraf, M.A. ‘The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based

view’, Strategic Management Journal 14(3) 1993, pp.179–91.

Porter, R. ‘A study of cartel stability: the Joint Executive Committee, 1880–

1886’, Bell Journal of Economics 14(2) 1983, pp.301–14.

Postrel, S. ‘Competing networks and proprietary standards: the case of

quadraphonic sound’, The Journal of Industrial Economics 39(2) 1990,

pp.169–85.

Sah R.K. and J.E. Stiglitz ‘The architecture of economic systems: hierarchies

and polyarchies’, American Economic Review 76(4) 1986, pp.716–27.

Saloner, G. ‘Modeling, game theory, and strategic management’, Strategic

Management Journal (12) 1991, pp.119–36.

Shapiro, C. and H. Varian Information rules. (Cambridge, MA: HBS Press, 1999)

[ISBN 97807875848631] Chapter 7 ‘Networks and Positive Feedback’.

Smith, K.G., W.J. Ferrier and H. Ndofor ‘Competitive dynamics research:

critique and future directions’ in M.A. Hitt, R.E. Freeman and J.S. Harrison

(eds), The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management. (Oxford: Blackwell

Publishing, 2001) pp.314–61.

Spence, A. ‘The learning curve and competition’, The Bell Journal of Economics

12(1) 1981, pp.49–70.

Wernerfelt, B. ‘The resource-based view of the firm’, Strategic Management

Journal 5(2) 1984, pp.171–80.

1.8 Online study resources

In addition to the subject guide and the Essential reading, it is crucial that

you take advantage of the study resources that are available online for this

course, including the VLE and the Online Library.

You can access the VLE, the Online Library and your University of London

email account via the Student Portal at:

http://my.londoninternational.ac.uk

You should have received your login details for the Student Portal with

your official offer, which was emailed to the address that you gave on

your application form. You have probably already logged in to the Student

Portal in order to register. As soon as you registered, you will automatically

have been granted access to the VLE, Online Library and your fully

functional University of London email account.

If you have forgotten these login details, please click on the ‘Forgotten

your password’ link on the login page.

The VLE

The VLE, which complements this subject guide, has been designed to

enhance your learning experience, providing additional support and a

sense of community. It forms an important part of your study experience

with the University of London and you should access it regularly.

5

MN3119 Strategy

The VLE provides a range of resources for EMFSS courses:

• Self-testing activities: Doing these allows you to test your own

understanding of subject material.

• Electronic study materials: The printed materials that you receive from

the University of London are available to download, including updated

reading lists and references.

• Past examination papers and Examiners’ commentaries: These provide

advice on how each examination question might best be answered.

• A student discussion forum: This is an open space for you to discuss

interests and experiences, seek support from your peers, work

collaboratively to solve problems and discuss subject material.

• Videos: There are recorded academic introductions to the subject,

interviews and debates and, for some courses, audio-visual tutorials

and conclusions.

• Recorded lectures: For some courses, where appropriate, the sessions

from previous years’ Study Weekends have been recorded and made

available.

• Study skills: Expert advice on preparing for examinations and

developing your digital literacy skills.

• Feedback forms.

Some of these resources are available for certain courses only, but we

are expanding our provision all the time and you should check the VLE

regularly for updates.

Making use of the Online Library

The Online Library contains a huge array of journal articles and other

resources to help you read widely and extensively.

To access the majority of resources via the Online Library you will either

need to use your University of London Student Portal login details, or you

will be required to register and use an Athens login: http://tinyurl.com/

ollathens

The easiest way to locate relevant content and journal articles in the

Online Library is to use the Summon search engine.

If you are having trouble finding an article listed in a reading list, try

removing any punctuation from the title, such as single quotation marks,

question marks and colons.

For further advice, please see the online help pages: www.external.shl.lon.

ac.uk/summon/about.php

1.9 The examination and examination advice

Important: the information and advice given in the following section

are based on the examination structure used at the time this guide was

written. Please note that subject guides may be used for several years.

Because of this we strongly advise you to always check both the current

Regulations for relevant information about the examination, and the VLE

where you should be advised of any forthcoming changes. You should also

carefully check the rubric/instructions on the paper you actually sit and

follow those instructions.

The examination will be a three-hour unseen written examination covering

all aspects of the syllabus. In the examination, you will be asked to:

6

Chapter 1: Introduction

• reproduce some knowledge. (This will get you close to a pass grade,

although some application is needed).

• apply knowledge to new situations. (This will lift you to the high lower

second, or low upper second marks (assuming you get all the above

questions right)) and

• make new connections between topics and/or phenomena. (This will

enable you to obtain a first class mark in this course).

As with most examinations, try to allocate your time approximately

proportional to the marks available. If you are having problems with an

analytical question that worth very few points, it’s best to let that one go

and avoid losing time that you could use on another question.

Remember, it is important to check the VLE for:

• up-to-date information on examination and assessment arrangements

for this course

• where available, past examination papers and Examiners’ commentaries

for the course which give advice on how each question might best be

answered.

1.10 The syllabus

Basic game theory: Two-player games. Static and dynamic games and

some examples. Equilibrium concepts and solution mechanisms – Nash

equilibrium, dominant/dominated strategies, backward induction.

Oligopoly competition: Perfect competition and monopoly. Price

competition and the Bertrand paradox. Quantity competition. Reaction

functions. Bertrand versus Cournot.

Analysis of market structure: Describing market structure: C4-ratio,

Herfindahl index, Lerner index and market power. Market definition –

techniques and interpretation.

Collusion: Cartels and antitrust. Cartel stability and the discount factor.

Market dynamics and stability of collusion.

Strategic Alliances: Portfolio test. Strategic and business partnerships.

Sources of complementarity. Resource accumulation. Absorptive capacity.

Organisation design: Organisational fit, Strategy and structure, Functional

organisation, Multidivisional structure, Worldwide structure.

Competitive Dynamics: Competitive dynamics, Competitive action,

Resource similarity, Market commonality, Awareness, motivation and

capability.

Strategic asymmetries: Economies of Scale, sources and consequences.

Scope Economies: Airline Hubs. Learning or experience curve. Firm

strategies with EoScale/Scope/Learning. First-mover advantages. Market

structure with increasing returns.

Value chain analysis and vertical relations: Double marginalisation and

its remedies. Vertical foreclosure. Retailer competition and investment

externalities.

Vertical integration and transaction cost: Make or Buy. Contracts. RelationSpecific Assets and Hold-Up. Economic Rents and Quasi-Rents.

Entry and entry deterrence: Structural determinants of entry. Entry barriers

and exit barriers. Entry deterrence. Identifying entrants.

Research and Development: Market structure and R&D intensity. R&D

rivalry. Monopolists’ and entrants’ R&D incentives. Risk choice of R&D.

7

MN3119 Strategy

Benefits of the patent system. Sleeping patents. Spillovers.

Technology adoption: Preemption games. Option value and future

technological generations. Technology diffusion: Heterogeneity, epidemic,

and population ecology approaches.

Network Effects: Direct and indirect network effects. Systems goods. Excess

inertia. Excess momentum. Firm strategies with network effects. Standards

Battles.

All topics are supplemented in the subject guide with specially written case

studies.

8

Chapter 2: The evolution of strategic management as an interdisciplinary field

Chapter 2: The evolution of strategic

management as an interdisciplinary field

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter, and having completed the Essential reading and

Activities, you should be able to:

• explain how the field of strategic management evolved over time

• discuss the elements of the shared meaning in the strategic

management field.

Essential reading

Hoskisson, R.E., M.A. Hitt and D. Wan W.P. Yiu, ‘Theory and research in

strategic management: swings of a pendulum’, Journal of Management,

25(3) 1999, pp.417–56.

Nag, R., D.C. Hambrick and M.-J. Chen, ‘What is strategic management,

really? Inductive derivation of a consensus definition of the field’, Strategic

Management Journal 28 2007, pp.935–55.

2.1 Introduction

Strategic management is a relatively young academic discipline. Among

the first publications are Alfred Chandler’s Strategy and structure (1962),

H. Igor Ansoff’s Corporate strategy (1965) and Kenneth Andrews’ The

concept of corporate strategy (1971). Since then the field has changed

its focus from business policy to strategic management and made the

transition from being a collection of toolkits developed by consulting

firms to a systematic, theory-driven academic field. In addition, right

from its beginning the area of strategic management was recognised as an

interdisciplinary research field. The field was – and is still – populated by

scholars from different disciplines like management, economics, finance,

marketing, psychology and sociology. For such a diverse field it might have

been difficult to develop a consensual meaning of what the discipline is all

about. However, such a shared understanding is important as all academic

fields are socially constructed and can only flourish if there is a shared

conception of its meaning. Thus, the purpose of this chapter is twofold:

first, we will sketch the evolution of the field before analysing the shared

understanding of the field.

2.2 Early theories

The field of strategic management or, to be more precise, the field of

business policy (as it was initially called) did not emerge before the 1960s

with the influential work of Alfred Chandler, Igor Ansoff and Kenneth

Andrews. These early writings were influenced by the work of Edith

Penrose, who developed a theory of the growth of the firm by emphasising

the importance of a firm’s resources and managerial capabilities for its

growth. Besides Penrose, these researchers were influenced by the work

of the Carnegie School, especially Herbert Simon, Richard Cyert and

James March, who developed the idea of bounded rationality to study the

decision-making process in firms. Deviating from standard economics,

Simon and his colleagues assumed that decision makers do not have

9

MN3119 Strategy

complete information and that the alternatives they are deciding upon

needs to be researched. The last important influence of the early writings

was the work by Philip Selznick and his idea on distinctive competences.

A distinctive competency is something that is unique to an organisation

and superior in some respects when compared with the competencies of

other organisations that offers some value to their customers. Influenced

by these ideas, Chandler, Ansoff and Andrews developed their theories of

strategy by placing an emphasis on the internal characteristics of a firm.

In Strategy and structure, for example, Alfred Chandler studied how large

organisations develop new administrative structures to accommodate

growth and how strategic change influences an organisation’s structure.

2.3 Michael Porter and the industrial organisation

paradigm

After relabelling the field ‘strategic management’ in the late 1970s, the

focus moved towards industrial organisation economics in both theory and

method. At this time research was aiming to develop and test hypotheses

derived from the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) paradigm. The

basic idea of this paradigm is that the performance of a firm is determined

by the industry in which it competes. The conduct of a firm is just a

reflection of the industry structure, so that the most important decision

a firm has to make is in which industry it wants to compete in. The SCP

paradigm led to a shift in focus from the firm to the industry or market

structure. The most influential scholar from this era is Michael Porter, who

is not only well known among researchers but also among practitioners.

He developed the so- called ‘five forces’ model that specified different

features of an industry and which determines its attractiveness and

facilitates competitor analysis. Porter also proposed the idea of generic

strategies – low cost leadership, differentiation and focus – to match the

characteristics of an industry and achieve a competitive advantage.

Besides the SCP paradigm, research at this time developed the idea of

strategic groups. Strategic groups are groups of firms in the same industry

who follow the same strategy, for example, all suitcase producers in the

high-price market like Louis Vuitton or Bottega Veneta.

A third important research theme, influenced by industrial organisation

economics, is competitive dynamics (which is subject of Chapter 13).

The basic interest of competitive dynamics is to investigate how firms

are jostling for competitive advantage by carrying out different types of

strategic and tactical actions.

2.4 Organisational economics

In the 1970s the field of strategic management was not only influenced

by the work of industrial economists but also by another subfield of

economics: organisational economics. Organisational economics tries to

open the ‘black box’ of the firm and looks at its inner structural logic and

functioning. Its most prominent theories are transaction cost economics

and agency theory.

Transaction cost economics, developed by the work of Oliver Williamson,

studies the question of why firms exist and which transactions are made

inside the market and which inside the firm. Building on the concept

of bounded rationality and asset specificity, Williamson argues that

transactions are made within the firm (or hierarchy, in the words of

Williamson) when the sum of all transaction costs is smaller than the price

10

Chapter 2: The evolution of strategic management as an interdisciplinary field

for the transaction in the market. He further argues that firms exit as an

efficient alternative to the market. Strategic management scholars have

applied transaction cost theory to study the make or buy decision of all

firms, including multidivisional and international firms.

Agency theory claims that the separation of ownership and control in

most organisations lead to a problem of divergence of interest between

shareholders (‘principals’ in the words of agency theory) and managers

(called agents). The idea is that managers try to maximise their utility,

which might not be in line with the maximisation of the long-term profits

of the firm. To avoid this problem, firms need contracts that rule the

relationship between principal and agents.

2.5 Resource-based view, dynamic capabilities and

leadership theory

One of the latest steps of the development in the field of strategic

management occurred with the emergence of the resource-based view and

its dynamic extension – the dynamic capability approach. This stream of

research is influenced by the work of Edith Penrose, who viewed the firm

as a collection of productive resources. The resource-based view further

argues that these resources are heterogeneously distributed among firms.

The differences in resources combined with the imperfect mobility of the

resources can explain the differences in performance among firms in the

same industry. The dynamic capability approach extends this logic and

argues that a firm needs dynamic capabilities to modify and extend its

resource base to achieve and sustain a competitive advantage or a series of

competitive advantages over time.

Finally, in 1984 Don Hambrick and Phylis Mason developed the strategic

leadership or upper echelons theory. They developed a theoretical

framework that proposed senior executives base their strategic choices

on their cognitive structures and values. Hence, strategic leadership

theory tries to explain differences in firms’ performance by, for example,

differences in past performances of their executives, top management

team size, composition and tenure.

2.6 A consensus definition of the field

As seen in this short historical overview, strategic management has been

advanced by researchers from different disciplines, especially economics,

organisation science or sociology. Such an interdisciplinary field often

lacks a clear understanding of or consensus on the subject. However,

without this consensus, a field is limited in its growth. As this is at odds

with the great success of the field of strategic management over the last 30

years, Nag et al. conducted a study among strategy scholars from different

disciplines asking them about their personal views of the field of strategic

management. In their large study among strategy researchers, they

found the following implicit definition of the field: The field of strategic

management deals with (a) the major intended and emergent initiatives;

(b) taken by general managers on behalf of owners; (c) involving

utilisation of resources; (d) to enhance the performance; (e) of firms; (f)

in their external environments. They therefore concluded that the success

of the field emerges from an underlying consensus that enables it to attract

multiple perspectives.

11

MN3119 Strategy

2.7 Key concepts

• Strategic management

• Business policy

• Structure-conduct-performance paradigm

• Transaction cost economics

• Agency theory

• Resource-based view

• Dynamic capabilities.

2.8 A reminder of your learning outcomes

Having completed this chapter, and the Essential reading and Activities,

you should be able to:

• explain how the field of strategic management evolved over time

• discuss the elements of the shared meaning of the strategic

management field.

12

Chapter 3: Analysis of market structure

Chapter 3: Analysis of market structure

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter, and having completed the Essential reading and

Activities, you should be able to:

• discuss the most common techniques used to define a market

• describe a firm’s market power within a defined market.

Essential reading

Besanko, D., D. Dranove, M. Shanley and S. Shaefer. Economics of Strategy

(New Jersey: Wiley, 2009) pp.205–11.

or

Lexecon Ltd An introduction to quantitative techniques in competition analysis.

Lexecon Ltd. publication, mimeo. Available at: www.crai.com/ecp/assets/

quantitative_techniques.pdf.

Saloner, Shepard and Podolny Strategic Management. (New Jersey: Wiley,

2005) Chapter 6.

Further reading

Emmons, W. and R. Prager ‘The effects of market structure and ownership

on prices and service offerings in the US cable television industry’, Rand

Journal of Economics 28(4) 1997, pp.732–50.

Geroski, P. ‘Thinking creatively about markets’, International Journal of

Industrial Organisation 16(6) 1998, pp­.677–95.

3.1 Introduction

In this chapter we will first present techniques which are used when

defining markets, for instance, for policy or firm strategy analysis. In

the second part of this chapter we introduce some methods of analysing

markets with many firms.

The process of market definition and analysis will be an input for the later

chapters in the second part where we will learn how to analyse tightly

structured problems, for example, by solving games having identified the

players, the strategies, the pay-offs and the rules.

3.2 Techniques of market definition1

Why should we want to define the market for a particular product or firm?

Geroski (1998) states that there are three ways of ‘thinking creatively

about markets’: trading markets, antitrust markets and strategic

markets. Trading markets are defined as geographical areas and a set of

products for which the law of one price holds to a certain degree. That is,

taking into account transport costs and slight differences in the product

offerings, we would expect a similar price to be charged for similar

products. Market definition from an antitrust perspective looks at the

likelihood that the market can be monopolised by a single firm, or group

of firms. That is, if there was some change in the degree of the market’s

competitiveness (for example, through mergers or collusive agreements),

would it be possible to initiate a ‘small and significant increase in prices’,

This section is based

mainly on Lexecon

Ltd An introduction to

quantatative techniques

in competition analysis.

1

13

MN3119 Strategy

or is market power restricted by other, closely related markets? Finally,

strategic market definition concerns itself with market boundaries

which are defined by firms’ product offerings. The argument here is that

companies not only adapt to but also create or segment markets in order

to maximise their profits.

We will introduce a number of techniques of market definition: estimating

the cross-price elasticity of demand, price correlation analysis, switching or

diversion ratio, shock analysis and bidding studies.

Example: Sony’s PlayStation 3 (PS3), a video game console

The PS3 was introduced in the year 2006 with the express intent of providing a successor

to the Playstation 2 and to challenge Microsoft’ s early mover position in the market for

256-bit game consoles. The simple definition of the market would suggest that the PS3’s

market is defined by ‘game consoles’. Hence, its main competitors are the Nintendo Wii,

the Microsoft X-Box 360, and Sony’s own Playstation 2 to some extent. Is this the whole

story? To start with, PCs nowadays have relatively advanced gaming features as well and

there is a large library of PC games available, which would suggest that PCs are also a

significant competitor also. Going even further, if young people no longer find playing

game consoles attractive, they could switch to other ways of entertaining themselves like

watching TV, reading books, playing board or ball games, etc. Another way of thinking

about the market for the PS3 is by looking at the buyers, who are more often than not

parents around Christmas time. What would they be spending their money on if not on

the PS3? This could be other consumer electronics as gifts or clothing, etc.

3.2.1 Cross-price elasticity of demand

You will recall the (own-price) elasticity of demand (e) from your

introductory microeconomics course: it is defined as the ‘relative change

in quantity (Q) demanded due to a price (P) change’. We can write the

own-price elasticity as:2

−

∂Qi

Qi

∂Pi

Pi

or −

∂Qi Pi

∂Pi Qi

The cross-price elasticity then measures the ‘relative change in quantity

demanded of one good, due to a one per cent price change of another

good’. We can write the formula as:

∂Qi Pj

∂Pj Qi

That is, if the price for another good goes up by one per cent, how will

demand for my own product change (in percentage terms)? If a product

is a close substitute, we would expect cross-price elasticity to be a large

positive number: a price increase of five per cent for a rival product will

redirect a lot of customers towards my own product, meaning that demand

goes up by more than five per cent. On the other hand, if a price decrease

for a potential substitute results in only small quantity losses, cross-price

elasticity is low and we can say that the products are distant substitutes.

This simple technique cannot be used to define or test a market. However,

it is a very powerful tool to assess the relationship of two products if the

data is available.

14

2

We leave out the

negative sign commonly

used in own-price

demand elasticity.

This is simply because

we expect cross-price

elasticity to be positive

for substitute products.

This is however just a

convention and nothing

should be read into it.

Chapter 3: Analysis of market structure

Activity 3.1

Give your estimates of the cross-price elasticities of the following product pairs and explain

why.

a. Two gas stations on opposite sides of the road

b. Coffee and tea

c. Hotels in Bahrain and New Zealand

Guidance on this activity can be found in the VLE.

3.2.2 Price correlation analysis

Quite often it is difficult to gather enough data to calculate the cross-price

elasticity of demand – in particular, obtaining a time series of quantity and

price data containing some small price changes and very little changes in the

general market parameters is typically difficult.

An (imperfect, but still acceptable) alternative may be tracking movements

of prices over an extended period of time. As we will see in Chapter 5, the

B and C competition model shows prices as strategic variables are strategic

complements, which means that, on the one hand, if one firm increases its

price, so will the other. In contrast, if quantities are the strategic variable

(and the strategies therefore are strategic substitutes), we expect market

prices emerging from the quantities set by the firms to move in unison for

related products. In the extreme case of perfect substitutes, the market price

for both will be the same, so an increase in price for one product implies a

price increase for the rival product.

A word of caution on the interpretation of price correlations: it is important

to rule out other explanations for the co-movement in prices. For example,

if the prices of ice cream and sunscreen are highly correlated, this does not

imply that the two are close substitutes – if anything, they are complements,

but demand for both of them is affected by the same (seasonal) components,

temperature and sun. Similarly, tyres and washing-up liquid are rarely

mistaken for substitutes, but changes in their prices are likely to occur at

somewhat similar times – both products use oil as a significant input3 and

are therefore likely to be affected by oil price changes in a similar way. The

point is that price correlations have to be interpreted with care and that

potential sources of ‘spurious correlation’ (i.e. correlation that is not down

to the reason stipulated) have to be taken into account. It is also important

to get a sense of the reasons for the price changes, even if they were not

‘spurious’ in the sense outlined above – were there any product or process

innovations (we will cover this later in the guide), was there a significant

shift in consumer preferences or did firms simply change their strategies?

A more comprehensive

list of products made

from oil is given on

www.anwr.org/features/

oiluses.htm

3

3.2.3 Switching/diversion ratio analysis

If a time series of prices is not available or if for some reason would not be

meaningful (for example, if one product is priced at zero, e.g. a software

programme available as freeware on the internet), it may be useful to ask

consumers directly for the products or services they perceive as the closest

substitutes to the products they are currently using.

Frequently, this will take the form of a survey of consumers of a particular

product or service who are asked a question to the tune of: ‘If the product

you have just purchased had not been available today, what other option

would you have chosen?’ Clearly, the more ‘votes’ a particular alternative

obtains, the closer a substitute it is likely to be.

15

MN3119 Strategy

3.2.4 Shock analysis

Another reliable method of determining the closeness of two products

or services is their reaction to a ‘shock’. Technically, this is a natural

experiment observing a sudden and unexpected change in one market

and analysing the reaction in the (possibly) related market. Shocks can

take many forms: entry of a new product, technological change, price

concessions, a change in input prices, natural crises, etc. For example,

when Sony released the Playstation 3 in 2006, board game manufacturers

made only limited changes to their strategies (and probably experienced

only a limited impact on their sales), whereas Nintendo and Microsoft

were hit relatively hard, suggesting that the game consoles market consists

of closer substitutes than the broadly defined ‘leisure’ industry.

3.2.5 Bidding studies

Finally, there may be cases where prices are not transparent or not

publicised, or where the number of transactions is relatively low so that

no meaningful correlations can be gathered from the data. Sometimes

therefore, the best that can be done is to determine ‘who bids for the

same business’ as a proxy of who competes in the same market. For

example, when the ‘big four’ accounting firms were still the ‘big six’, the

effect of merging PriceWaterhouse and Coopers & Lybrand was assessed

using a bidding study. On the one hand, it was found that in addition to

PriceWaterhouse and Coopers & Lybrand, the other four accountancy

firms were bidding for very similar projects or accounts, which meant that

competition was likely to be intense even after the two merged. On the

other hand, if the two merging partners had been a duopoly in a submarket, say, large manufacturing accounts in the north-east of England,

the merger would have led to a monopoly in the north-east manufacturing

sector. So, while bidding studies are a relatively crude way of determining

one’s competitors, they are still a useful exercise.

3.3 Market analysis with many firms

Suppose now that we have defined the market using one (or multiple) of

the techniques introduced above. What next? We need to find some

proxies for determining whether the market is competitive or not, in-order

to judge, for instance, how attractive the market is likely to be in the near

future, how likely it is that antitrust action will be taken, and if entry or

exit by rivals can be expected.4

Figure 3.1 gives the four most commonly used measures of

competitiveness and concentration in an industry. Their quality and

accuracy increase from number one to four:

The simplest way to measure the competitiveness of a market is by

counting the number of firms in an industry. In a market with many

firms, it is less likely that a single firm will have a significant amount of

market power. Further, more firms suggest rather low entry barriers (the

more firms there are, the lower the average size or market share per

firm in the industry is lower the more firms there are), which is another

indicator for a competitive market. If there are some firms, however, that

do have significantly higher market power than others in the industry, a

simple count would not do the trick.

16

4

We will discuss

entry in more detail in

Chapter 14. For now it is

sufficient to know that a

less competitive market

is likely to be more

profitable for potential

entrants, which in turn

implies that incumbents

will try and build barriers

to entry to maintain

their profitable position.

Chapter 3: Analysis of market structure

1. #firms

2. C4/5/8

C≡

1

n

4

C4 ≡ ∑ si

i =1

3. Herfindahl index

n

H ≡ ∑ si2

i =1

n

4. Lerner index

L ≡ ∑ si

i =1

p-MC i

p

Figure 3.1: Measures of competitiveness and concentration.

A more useful method, particularly if there are several larger firms, is to

calculate the Cn-ratio (mostly C4, C5 or C8) – the sum of the market shares

of the n largest firms. This gives some information about how strong the

biggest firms are likely to be. Again, however, this measure is not fully

satisfactory: Imagine a market with 4 firms – the C4-ratio will be 100 per

cent regardless of the distribution of market shares between the four firms.

Similarly, if the n+1th largest firm is almost as big as the nth firm, the

Cn-ratio will not pick this up. So even though we can do a little better than

simply counting the firms, not all information is utilised in the Cn-ratio.

The Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) takes the market shares

of all the firms in an industry into account and sums their squares. This

solves a lot of the problems of the previous two concentration indices:

first, information of all firms is taken into account,5 and second, larger

firms feature more prominently in the index. The HHI is a standard tool

for antitrust economists and the US Department of Justice guidelines state

that ‘…markets in which the HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800 points are

considered to be moderately concentrated, and those in which the HHI is

in excess of 1,800 points are considered to be concentrated. Transactions

that increase the HHI by more than 100 points in concentrated markets

presumptively raise antitrust concerns under the Horizontal Merger

Guidelines issued by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade

Commission.’6

The one remaining problem with the HHI is that while it says a lot about

the size distribution of firms within an industry, it does not say anything

about the way and intensity with which these firms compete, or, in

economists’ parlance, their conduct. The Lerner index, then, takes

the HHI one step further and looks at a firm’s profit margins (i.e. price

– marginal cost) and weighs them by the firm’s market share. In other

words, if the largest firm charges a high price relative to its marginal cost

while smaller ones price relatively aggressively, the Lerner index will be