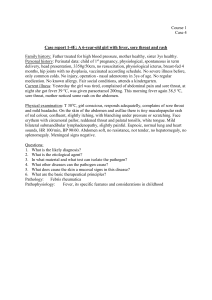

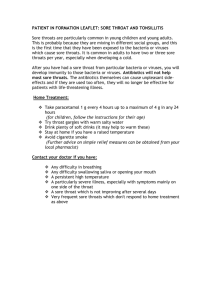

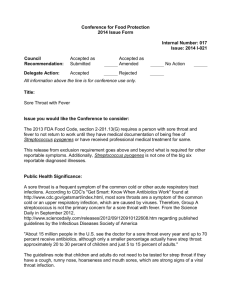

ESCMID Guideline For The Management Of Acute Sore Throat

advertisement