A defining moment

Oct. 22, 2014

A defining moment

When a white fan of the St. Louis Rams tried to steal an American flag from a black

Ferguson protester outside the Edward Jones

Dome on Sunday, the image of the

interaction caught by Post-Dispatch photographer David Carson reminded

Patricia Bynes of a poem by Langston

Hughes.

Ms. Bynes, a Democratic committeewoman in Ferguson, has been a fixture at the Ferguson protests since Aug. 9, the day 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot. At times she has been a quiet, calming voice. At times she has sounded a passionate trumpet for change, showing the world the various sides of the black experience in north St. Louis County.

“I, too, am America,” wrote Mr. Hughes, who was born in Joplin. An African-

American, he was one of the country’s great

20th century poets. “I am the darker brother,” the poem continues.

•••

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

•••

Over the past two and a half months, black

St. Louis and white St. Louis have recognized in meaningful ways that regardless of one’s views on the still undetermined specifics of how and why

Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson shot

Mr. Brown, racial disparity has fed the community’s narrative for too long.

The Ferguson movement, in its various forms, has grown strong enough that on

Tuesday, Gov. Jay Nixon used the power of state government to give St. Louis the opportunity to change itself, to heal, to move forward, to find unity in our historical division.

The governor has been criticized, including by this editorial page, for being slow to recognize the historic opportunity for change that the Ferguson protests offer the St. Louis region. But he’s here now, and in creating a Ferguson Commission, he has set the table for important, potentially groundbreaking conversations.

“To move forward, we must transcend anger and fear. We must move past pain and disappointment,” Mr. Nixon said on

Tuesday. With a touch of humility rarely shared publicly by the governor, he recounted his own upbringing in rural De

Soto, with whites living on one side of the railroad tracks, blacks on the other. “We must open our hearts and minds to what others have seen, what others have lived, and respect their truth. That is the challenge that lies before us.”

Now comes the heavy lifting.

The governor has given the community a charge: Examine the social and economic conditions “underscored by the unrest” and make specific recommendations to create “a stronger, fairer place for everyone to live.”

That’s a broad but immensely important task. For the Ferguson Commission to be successful, the first step will be the hardest.

Who gets a seat at the table?

•••

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

‘Eat in the kitchen,’

Then.

•••

The Ferguson Commission will need to be led by the region’s great academic institutions, by professionals who will let the research lead them, by people who are used to listening and appreciating competing points of view. But it can’t be an echo chamber.

Some Ferguson protesters will have to get past their mistrust of Mr. Nixon and accept that he is responding to the community. Politicians, particularly, will have to get past decades of grievances that have nothing to do with Ferguson. They

must make sure that all elements of the community have a seat at the table.

What does that mean? That means young, black protesters will have to share a seat at the table with law enforcement officials who might believe that Mr. Wilson is innocent. It means state senators such as Maria

Chappelle-Nadal and Jamilah Nasheed, both of whom have made a few outlandish remarks during the protests, will have to be represented in some capacity on the commission, and they’ll have to step up their game.

It means rivals like Mayor Francis Slay and 21st Ward Alderman Antonio French will have to work together. It means business leaders like Civic Progress and community activists who have protested at corporate headquarters will have to shake hands and agree to help the community move forward.

Hugh Grant, the chairman and CEO of

Monsanto, and president of Civic Progress, knows that St. Louis stands at a precipice that will determine the city’s future for decades.

“Ferguson,” he told us, “is the fracture point that fundamentally changes St. Louis, or else everything crystallizes and nothing changes. In our lifetime, you might not ever have another chance to swing at the fences.”

This is what the Ferguson Commission must do: Get the right people at the table and swing for the fences. Much of what must be done is already clear:

• The region must break down a municipal police and court system that preys on the poor, treating them as chickens to be plucked rather than citizens to be served and protected. Last week’s Better Together report added further fuel to that blazing fire, finding that while the 90 municipalities in

St. Louis County make up 11 percent of the state’s population, the courts from those municipalities bring in a whopping 34 percent of all municipal court revenue statewide. Twenty of the 21 cities in the county that derive at least 20 percent of their revenue from courts are in areas that are predominantly African-American. This must change. It must change now.

• It’s time to stop tip-toeing around the fact that our region’s division, often along black and white lines, is making us weaker.

Call it city-county merger, call it consolidation or collaboration, call it whatever you want. It’s time for a One St.

Louis movement to begin. The Ferguson

Commission can help us get there.

• Our division feeds another problem:

There are too many police forces, some of them lacking accreditation, most of them failing to come anywhere near to representing their community along racial lines. The law enforcement community has already recognized this problem, but it runs deep. It is tied to racial profiling, which must be more closely studied. It is tied to our region’s history of dividing by race. It is tied to a police culture more likely to see a young, black male as a threat than a recruit.

It’s tied to a black culture in which helping police solve crimes is seen as “snitching.”

Other cities have dealt with these issues, with the help of the U.S. Department of

Justice. St. Louis, and the Ferguson

Commission, will need such outside help.

• There is the education component. The region has some of the finest public schools in the state and some of the worst. The ongoing tragedy of the transfer crisis at the unaccredited Normandy and Riverview

Gardens districts makes that abundantly clear. There must be only one accepted standard for schools: Excellence.

• Race is the fundamental issue. When

Ferguson protesters, most of them black, have met white Cardinals and Rams fans, there has been anger. Conflict. Racist remarks caught on video for all to see. This is the ugly underbelly of St. Louis that much of the white community doesn’t want to deal

with. But it’s real. In personal, one-on-one conversations, and in big ones under the umbrella of the Ferguson Commission, this is the conversation that must change St.

Louis forever.

“Besides,” Mr. Hughes wrote in ending his poem, “I, Too”: “They’ll see how beautiful I am.”

•••

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

•••

Ferguson has brought everybody in St.

Louis to the table for a difficult, painful conversation. It is going to take awhile to go beyond conversations to real change. There will be some uncomfortable moments. But our city’s future, not just for African-

Americans living in poverty, but for Fortune

500 companies competing globally, depends on us getting it right.

America has seen our shame. Now, as

Mr. Nixon said, it’s time to show “the true colors of courage.”

A L E E E N T E R P R I S E S N E W S PA P E R • F O U N D E D B Y J O S E P H P U L I T Z E R D E C . 1 2 , 1 8 7 8

WEDNESDAY • 10.22.2014 • A14

A DEFINING MOMENT

Our view • Nixon creates a Ferguson Commission. Now the heavy lifting begins.

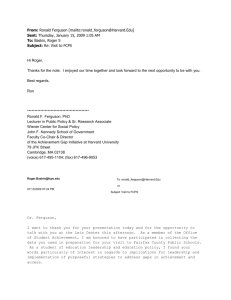

When a white fan of the St. Louis Rams tried to steal an American flag from a black Ferguson protester outside the

Edward Jones Dome on Sunday, the image of the interaction caught by Post-

Dispatch photographer David Carson reminded Patricia Bynes of a poem by

Langston Hughes.

Ms. Bynes, a Democratic committeewoman in Ferguson, has been a fixture at the Ferguson protests since Aug. 9, the day 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot.

At times she has been a quiet, calming voice. At times she has sounded a passionate trumpet for change, showing the world the various sides of the black experience in north St. Louis County.

“I, too, am America,” wrote Mr. Hughes, who was born in Joplin. An African-

American, he was one of the country’s great 20th century poets. “I am the darker brother,” the poem continues.

•••

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

•••

Over the past two and a half months, black St. Louis and white St. Louis have recognized in meaningful ways that regardless of one’s views on the still undetermined specifics of how and why Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson shot Mr.

Brown, racial disparity has fed the community’s narrative for too long.

The Ferguson movement, in its various forms, has grown strong enough that on

Tuesday, Gov. Jay Nixon used the power of state government to give St. Louis the opportunity to change itself, to heal, to move forward, to find unity in our historical division.

The governor has been criticized, including by this editorial page, for being slow to recognize the historic opportunity for change that the Ferguson protests offer the St. Louis region. But he’s here now, and in creating a Ferguson Commission, he has set the table for important, potentially groundbreaking conversations.

“To move forward, we must transcend anger and fear. We must move past pain and disappointment,” Mr. Nixon said on Tuesday. With a touch of humility rarely shared publicly by the governor, he recounted his own upbringing in rural De

Soto, with whites living on one side of the railroad tracks, blacks on the other. “We must open our hearts and minds to what others have seen, what others have lived, and respect their truth. That is the challenge that lies before us.”

Now comes the heavy lifting.

The governor has given the community a charge: Examine the social and economic conditions “underscored by the unrest” and make specific recommendations to create “a stronger, fairer place

DAVID CARSON • dcarson@post-dispatch.com

A football fan tries to grab a fl ag from a Ferguson protester during a melee outside the

Edward Jones Dome after the Rams game on Sunday.

for everyone to live.” That’s a broad but immensely important task. For the Ferguson Commission to be successful, the first step will be the hardest. Who gets a seat at the table?

•••

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

‘Eat in the kitchen,’

Then.

•••

The Ferguson Commission will need to be led by the region’s great academic institutions, by professionals who will let the research lead them, by people who are used to listening and appreciating competing points of view. But it can’t be an echo chamber.

Some Ferguson protesters will have to get past their mistrust of Mr. Nixon and accept that he is responding to the community. Politicians, particularly, will have to get past decades of grievances that have nothing to do with Ferguson. They must make sure that all elements of the community have a seat at the table.

What does that mean?

Wilson is innocent. It means state senators such as Maria Chappelle-Nadal and

Jamilah Nasheed, both of whom have made a few outlandish remarks during the protests, will have to be represented in some capacity on the commission, and they’ll have to step up their game.

It means rivals like Mayor Francis Slay and 21st Ward Alderman Antonio French will have to work together. It means business leaders like Civic Progress and community activists who have protested at corporate headquarters will have to shake hands and agree to help the community move forward.

Hugh Grant, the chairman and CEO of Monsanto, and president of Civic

Progress, knows that St. Louis stands at a precipice that will determine the city’s future for decades.

“Ferguson,” he told us, “is the fracture point that fundamentally changes St.

Louis, or else everything crystallizes and nothing changes. In our lifetime, you might not ever have another chance to

That means young, black protesters will have to share

Gov. Jay Nixon a seat at the table with law enforcement officials who might believe that Mr. swing at the fences.”

This is what the Ferguson Commission must do: Get the right people at the table and swing for the fences. Much of what must be done is already clear:

• The region must break down a municipal police and court system that preys on the poor, treating them as chickens to be plucked rather than citizens to be served and protected. Last week’s

Better Together report added further fuel to that blazing fire, finding that while the 90 municipalities in St. Louis County make up 11 percent of the state’s population, the courts from those municipalities bring in a whopping 34 percent of all municipal court revenue statewide. Twenty of the 21 cities in the county that derive at least 20 percent of their revenue from courts are in areas that are predominantly African-

American. This must change. It must change now.

• It’s time to stop tip-toeing around the fact that our region’s division, often along black and white lines, is making us weaker. Call it city-county merger, call it consolidation or collaboration, call it whatever you want. It’s time for a One St.

Louis movement to begin. The Ferguson

Commission can help us get there.

• Our division feeds another problem:

There are too many police forces, some of them lacking accreditation, most of them failing to come anywhere near to representing their community along racial lines. The law enforcement community has already recognized this problem, but it runs deep. It is tied to racial profiling, which must be more closely studied. It is tied to our region’s history of dividing by race. It is tied to a police culture more likely to see a young, black male as a threat than a recruit. It’s tied to a black culture in which helping police solve crimes is seen as “snitching.” Other cities have dealt with these issues, with the help of the U.S.

Department of Justice. St. Louis, and the

Ferguson Commission, will need such outside help.

• There is the education component.

The region has some of the finest public schools in the state and some of the worst.

The ongoing tragedy of the transfer crisis at the unaccredited Normandy and

Riverview Gardens districts makes that abundantly clear. There must be only one accepted standard for schools: Excellence.

• Race is the fundamental issue. When

Ferguson protesters, most of them black, have met white Cardinals and Rams fans, there has been anger. Conflict. Racist remarks caught on video for all to see. This is the ugly underbelly of St. Louis that much of the white community doesn’t want to deal with. But it’s real. In personal, one-on-one conversations, and in big ones under the umbrella of the Ferguson

Commission, this is the conversation that must change St. Louis forever.

“Besides,” Mr. Hughes wrote in ending his poem, “I, Too”: “They’ll see how beautiful I am.”

•••

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

•••

Ferguson has brought everybody in St.

Louis to the table for a difficult, painful conversation. It is going to take awhile to go beyond conversations to real change.

There will be some uncomfortable moments. But our city’s future, not just for African-Americans living in poverty, but for Fortune 500 companies competing globally, depends on us getting it right.

America has seen our shame. Now, as

Mr. Nixon said, it’s time to show “the true colors of courage.”

YOUR VIEWS • LETTERS FROM OUR READERS

Mother’s way of tackling mental illness is truly impressive

Regarding “After son’s suicide, mother builds a place to connect” (Oct. 19):

I loved this story! It is wonderful for Sally

Barker to do this to help others from dying from the isolation and horrifi c disease of depression. This is truly a fantastic way to memorialize her son and mostly to help save lives. The truly impressive part is that the website is monitored by counselors.

How awesome, that if someone needs immediate help, someone can get help to them. It is easily and readily available to all.

Thanks also to Ms. Barker for not contributing to the stigma of mental illness and putting the true reason for her son’s death out there. We do need to be more open and honest about mental illness. Mental illness is no respecter of socioeconomic class, gender, age, race, religion, country or anything else. It hits a broad cross-section of all societies. There is help available. Many people need therapy, family support and medication to mitigate and help control the illness, sometimes for life. Sadly in this case, it was not enough.

Depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other mental illnesses impact the quality of life, not only of the one who suffers the illness, but the family and friends around them as well.

My heart, thoughts, prayers and gratitude go out to this unselfish woman who is giving her all to try to save others the fate that her son and she suffered due to this ferocious illness. May others use this site, eradicate at least some of their loneliness and hang on the get the help they need — and may many lives be saved!

Jerry S. Hutter • Florissant a partial, yet significant fulfillment of that promise of an education.

Mike Harvey • O’Fallon, Ill.

College campus is appropriate place for protesters

As I began to read the article on the St. Louis

University protests (“Protests linger at SLU, leaving staff, students bemused,” Oct. 18), I was reminded of my own “awakening” on campus during the tumultuous days of the late 1960s and early ’70s. That was, until I read the accounts of the concerned helicopter parents descending on the campus from the likes of Chesterfield to insure that the protective cocoons enclosing little Buffy,

Missy and Muffy were not disturbed.

While I do not necessarily agree with all of the messages and methods of the protesters, there is no more traditional nor appropriate place for the open exchange of ideas and perspectives than our college campuses. For those students who do not understand the reason behind the selection of SLU as the stage for the protests, I would off er that their consideration of the question was already a benefi t of the “forced” engagement.

And to Ms. Cotton, who is concerned about the impact of the protesters on her daughter’s hard work and the $45,000 the family has paid to get a SLU education, I would respond that her daughter’s increased awareness and contact with the world and issues outside of the cocoon are

Vote no on early voting amendment

The League of Women Voters usually supports early voting. Not this time! We strongly oppose Constitutional Amendment 6 on the Nov. 4 ballot. Amendment

6 allows for an early voting system that is a complete sham.

This amendment would:

• Rely on the Legislature to fund early voting every year. It could simply refuse to fund it.

• Allow early voting for six business days during normal business hours. It is not stipulated what those days are. This would be very confusing to voters.

• Prohibit voting on weekends, which eliminates the ability to vote outside of regular business hours.

• Allow voting only at a single location in each county, such as the county clerk’s or Election Board offi ce. This clearly could pose a transportation issue for citizens who have enough diffi polling place.

If approved, this system would be very diffi system of early voting or just improvements in the process, such as weekend voting, would require another constitutional amendment and a statewide vote.

While only a simple majority is required to pass Amendment 6, a two-thirds majority would be required to repeal and replace it.

Amendment 6 would put in place a more restrictive system than in 29 other states, including the neighboring states of Iowa,

Kansas, Illinois and Arkansas.

The league strongly supports the concept of early voting to expand voting opportunities for everyone by expanding days, hours and locations to vote before Election Day.

This version of early voting is wrong for

Missouri.

Linda C. McDaniel and Kathleen Farrell •

Brentwood

Co-presidents, League of Women Voters of

St. Louis

Church must follow biblical authority on homosexuals

Regarding “Gays have gifts to offer church, bishops say” (Oct. 14):

In discussing their attitude toward homosexuals, did the Catholic hierarchy never mention biblical authority? It’s not a matter of progress versus tradition, but what God says in his word.

I am reminded of years ago when there was a headline saying “Billy Graham says

God loves homosexuals.” It just didn’t include the rest of his sentence: “... just like other sinners.” Pope Francis does not specifically deny Scripture. God does love sinners and wants them to be allowed into the church services, but that doesn’t mean he approves of what he still calls sin.

Doris Evans • Chesterfi eld

RAY FARRIS PRESIDENT & PUBLISHER GILBERT BAILON EDITOR TONY MESSENGER EDITORIAL PAGE EDITOR

THE PLATFORM

TM

STLtoday.com/ThePlatform

Find us at facebook/PDPlatform

Follow us on twitter @PDEditorial

PLATFORM • I know that my retirement will make no diff erence in its cardinal principles, that it will always fi ght for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fi ght demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfi ed with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty

• JOSEPH PULITZER • APRIL 10, 1907

WE WELCOME YOUR LETTERS AND E-MAIL

Letters should be 250 words or fewer. Please include your name, address and phone number.

All letters are subject to editing. Writers usually will not be published more than once every

60 days. Additional letters are posted online at STLtoday.com/letters .

Letters to the editor

St. Louis Post-Dispatch,

900 N. Tucker Blvd.

St. Louis, MO 63101

E-MAIL letters@post-dispatch.com

FAX

314-340-3139

TONY MESSENGER tmessenger@post-dispatch.com

Editorial Page Editor • 314-340-8382

KEVIN HORRIGAN khorrigan@post-dispatch.com

Deputy Editorial Page Editor • 314-340-8135

FRANK REUST freust@post-dispatch.com

Letters Editor • 314-340-8356

DEBORAH PETERSON dpeterson@post-dispatch.com

Editorial writer • 314-340-8276