Differences between ordinary and academic writing

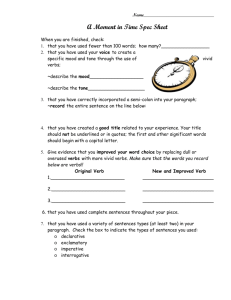

advertisement

Differences between ordinary and academic writing The following are more typical of ordinary, colloquial, non-scientific, or non-technical writing, versus academic, technical, and scientific writing. ordinary / informal writing academic / technical writing structure Fairly flexible structures Rigid article or essay structure, e..g., literature review; experimental design, materials and procedures; data results; discussion of results; general discussion genre Writing that is more colloquial or Formal, rigid styles like essay, lab report, conversation in style case study, research paper, thesis, literature review sentence structure Simple sentences; sentences combined by coordination (coordinate / independent clauses, 등위절) Sentences combined more often by subordination (subordinate / dependent clauses – 종속절), and participle phrases introductions Introductions are more general; may begin with more common, familiar knowledge, or attentiongetting statements More specific, leading specifically to an explicit thesis statement; intros more informative and concise, and often seem more direct or dry in style topic sentences Topic sentences may be at the start or end of a paragraph, or omitted altogether. Paragraphs usually start with a concise, direct statement of the main point, followed by supporting arguments or evidence topic transitions Shifts to new topics sometimes by means of there is/are expressions; reshifts to previous topics with expressions like as to, as for, regarding, as regards, speaking of... Shifts to new topics and reshifts done simply by starting sentences with full noun subjects, paragraph breaks, and transitions (yet, however, in contrast...); few reshift markers or there is/are expressions; relatively less use of expressions like as to, as for, regarding, as regards, speaking of... vocabulary Simpler and higher-frequency vocabulary; more phrasal verbs Lower-frequency vocabulary; more complex words, with many multisyllabic words from Latin and Greek vocabulary usage Some redundancy or repetition of words or ideas Highly dense text; very concise; very precise expression; minimal repetition (except for sentence subjects) 1 ordinary / informal writing academic / technical writing vocabulary choice Words are used with more common meanings (e.g., ‘theory’ = conjecture) Words have more specific, technical meanings (e.g., ‘theory’ =conceptual framework) demonstratives Demonstratives (this, that, these, those) used to refer to immediate antecedents or referents – previously mentioned things or persons Demonstratives, especially ‘this,’ often used to refer to discourse referents – previously mentioned ideas, phrases, sentences, e.g.: “this [fact, situation, etc.] merits further study,” “this situation / result / matter poses problems for...” and “the common use of X differs from that in academic parlance” sentence subjects Sentences begin with animate and personal nouns, personal pronouns (including first or second person pronouns) Sentences begin with full noun phrases; repetition of full nouns for clarity across sentences; pronouns, if used, are third person verb choice More modals, phrasal verbs, common verbs; verbs more often refer to actions (and thus, subjects are agents or doers of actions) Fewer modals or phrasal verbs; Latinate / Greek verbs; more abstract and relational verbs (e.g., ‘correlate, is consistent with) for concepts and conceptual relations verb forms More active verbs, get-passive (e.g., ‘got replaced’) More passive voice (be-passive, e.g., ‘was replaced’) nouns Fewer nominalizations More nominalizations, leading to a denser style (see below) tone More personal, even subjective; less formal (e.g., ‘cool study’ or ‘fishy analysis’) More impersonal and authoritative; more formal (e.g., ‘rigorous and insightful study’ or ‘questionable analysis’) Technical vocabulary Many words in academic discourse have more specific and complex meanings than in more ordinary writing. For example, in ordinary parlance, ‘theory’ means ‘conjecture, idea, hypothesis, something that has not been proven’; but in science, a theory is a complex, explanatory, scientific conceptual framework, and a scientific theory can be one that has been proven and accepted, or one that is not yet proven (thus, the theory of evolution is by no means an hypothesis or conjecture, but a proven and universally accepted theory). Likewise, the ordinary use of ‘correlation’ differs from that of quantitative research, where ‘correlation’ indicates a statistical relationship that meets certain statistical criteria (like statistical significance). Some terms like ‘statistical significance’ may be opaque or alien to a person who has not studied statistics or who has not been taught the concept properly. Even ordinary terms like ‘gravity’ has a different nuance; in ordinary parlance, it is simply a force that makes objects fall, but a physicist’s understanding and usage of the term ‘gravity’ is more technical and precise. ‘Mass’ and ‘matter’ may mean the same thing to non-scientists, but these are very different concepts 2 for physicist. The following types of vocabulary are also more typical of formal writing. • Reporting verbs: More formal, specific verbs like report, note, cite, indicate, claim, posit, discuss, suggest are used to report what others have written, rather than informal verbs like say, mention. • Classifier / evaluative nouns: class, type, category, issue, matter, problem • Explicit cause – result expressions: outcome, yield, produce, result, leads to, contributes to, correlates with, effect, finish • Objective evaluative expressions: advantage, disadvantage, problem, advantage, angle, aspect, attempt, branch, category, circumstance, class, consequence, course [of action], criterion, deal, disadvantage, drawback, element. fact, facet, factor, form, item, motive, period, plan, problem, reason. stage, term, type. Words with a neutral, objective tone are used rather than overly negative or positive terms. Topic sentences A more informal or less skilled topic sentence is the “self-announcing” topic sentences. I want to argue that this policy will not only fail to bring about any positive results, but in fact will ultimately compromise the quality of classroom teaching. Also, some writers may write in a less fluid style like this. Korean texts have been analyzed by applied linguist Eggington. He shows that Korean texts are characterized by indirectness and nonlinear development. A four-part pattern, ki-sung-chon-kyul, typical of Korean prose, contributes to the nonlinearity (Conner, 1996:45). Nominalizations It is more common in technical writing to reduce an entire phrase or idea to a single noun phrase; e.g.: simple, less formal nominalization Gutenberg invented the printing press, which allowed people to disseminate information Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press revolutionized the dissemination of information we applied...; how we applied...; where we applied... our application of... how we directed the research; the direction that our research took the direction of our research 3 The following example shows how scientific writing uses nominalizations, passive verbs, and participle phrases. The original1 on the left compares with the less formal rewording on the right. more formal (original) less formal (modified) Human cellular models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis would enable the investigation of candidate pathogenic mechanisms in AD and the testing and developing of new therapeutic strategies. Human cellular models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis would enable us to investigate candidate pathogenetic mechanisms in AD, and would enable us to test and develop new therapeutic strategies. We report the development of AD pathologies in cortical neurons generated from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells derived from patients with Down syndrome. We report on how we developed AD pathologies in cortical neurons that were generated from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells that were derived from patients with Down syndrome. These cortical neurons processed the transmembrane APP protein, resulting in secretion of the pathogenic peptide fragment amyloid-β42 (Aβ42). These cortical neurons processed the transmembrane APP protein, which resulted in secretion of the pathogenic peptide fragment. Production of Aβ peptides was blocked by a γ-secretase inhibitor. Aβ peptides were not produced, because they were blocked by a γ-secretase inhibitor. Finally, hyperphosphorylated tau protein, a pathological hallmark of AD, was found to be localized to cell bodies and dendrites in iPS cell–derived cortical neurons from Down syndrome patients, recapitulating later stages of the AD pathogenic process. Finally, we found that hyperphosphorylated tau protein, a pathological hallmark of AD, was localized to cell bodies and dendrites in iPS cell–derived cortical neurons from Down syndrome patients. This recapitulates later stages of the AD pathogenic process. References 1. Conner, Ulla. (1996). Contrastive Rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2. Snow, Catherine E. (2010). Academic language and the challenge of reading for learning about science. Science, 328, 450-452. [and references therein] 3. Swales, J. M. & Feak, C. B. (2004). Academic writing for graduate students. 2nd ed. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. 1 Original text from Y. Shi, P. Kirwan, J. Smith, G. MacLean, S. H. Orkin, F. J. Livesey. (2012). A Human Stem Cell Model of Early Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in Down Syndrome. Science Translational Medicine, 4, 124ra29. 4 5