- Kritika Kultura

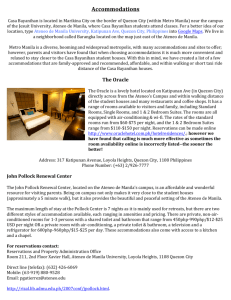

advertisement