drama, greek - DanversTown

advertisement

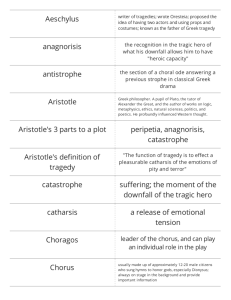

DRAMA, GREEK however, did serve to strengthen Athens as a political unit. For the first time, murder cases had to be submitted for public trial, ending much feuding and bloodshed. (See also Law, Greek.) DRAMA, GREEK * classical relating to the civilization of ancient Greece and Rome * Renaissance period of the rebirth of interest in classical art, literature, and learning that occurred in Europe from the late 1300s through the 1500s * deity god or goddess * epic long poem about legendary or historical heroes, written in a grand style ' hero in mythology, a person of great strength or ability, often descended from a god D rama of the Western world was born in Greece. People throughout the ancient Mediterranean world imitated Greek plays and Greek methods of performing plays on stage. Centuries later, when Europeans rediscovered classical* Greek literature during the Renaissance*, educated people regarded the Greek plays as the model of dramatic perfection. Even in the modern era, writers and actors have been influenced by the traditions of ancient Greek drama, as well as by specific Greek plays. ORIGINS OF GREEK DRAMA. The origins of Greek drama lie in religious celebrations honoring the Greek deities* during festivals or on holy days. Many of these celebrations included elements of acting and stagecraft. For example, each year priests at the shrine of Eleusis, near Athens, reenacted the death and resurrection of the goddess PERSEPHONE. Many festivals honored DIONYSUS, the god of wine and fertility. These festivals were accompanied by banquets, where singers led crowds in improvised songs, called dithyrambs. A chorus, a group of dancers and singers, accompanied these celebrations. As the dithyramb was chanted, the chorus would perform a circular dance around the altar of Dionysus. Both large cities and smaller communities had choruses. Eventually, local poets began writing accounts of the adventures of the gods and goddesses for the choruses to recite. During festivals, professional storytellers also recited the Iliad and the Odyssey, HOMER'S epics*. At some point, the emphasis shifted from reciting stories about the gods to acting them out. According to Greek legend, a performer named Thespis invented the art of acting when he stepped forward from the chorus and sang by himself, not about the god but as the god. Whether or not he single-handedly created the new art form, there was a real actor and playwright named Thespis who performed in Athens in the 500s B.C. Actors today are called thespians to honor his legendary contribution to drama. Greek drama developed further as poets began writing scenes for performers to act out. Many of these scenes involved legendary or historical heroes* and kings as well as deities. The drama combined traditional recitations and songs by the chorus with actions and speeches by individual actors. Actors wore masks and used words and gestures that enabled the audience to identify familiar characters. By the early 400s B.C., Greek drama had evolved into two distinct kinds of plays, tragedies and comedies, written for and performed at competitive drama festivals. All surviving examples of Greek drama were originally written for the festivals in Athens. TRAGEDY. Tragedies were serious plays dealing with the sufferings and trials of noble or heroic characters. Most tragedies concerned mythological or historical figures. Playwrights attempted to create suspense, to manipulate the audience's feelings of pity and fear, and to illustrate moral truths. The subject matter of a tragic play would have been familiar to the 17 DRAMA,GREEK e color plate8, vol. 3 audience andwould probably have been usedby other playwrights. For example, threedifferentplaywrights wrote dramas concerning the legendary storyof ORESTES how murdered hismother. The playwright's originality lay in how headapted such well-known tales and introduced new meanings andpointsofviewto theaudience. Through tragic drama, playwrights and audiences grappled with large, complex issues, such as the nature ofdivinity,justice, heroism, anddestiny Only 33 plays remain fromthegolden age of Greek tragedy in the 400sB.C. Most of these AESCHYLUS, plays by EURIPIDES SOPHOCLES, andsurvived because, several centuries afterthey were written, critics in the Egyptian cityofAlexandriaandelsewhere chose them for inclusion in schoolbooks. After Thespis,theGreeks regarded Aeschylus as the second father ofdrama.Hisplays dealt with large, philosophic questions, such as the natureofvirtueandjustice, and heusually wrote aboutfigures great from the remote, mythical past.Aeschylus's plays are noted for their majestic language. Sophocles,on theother hand, wrote plays that focused on human interactions. Sophocles introduced third a actor in his plays (Aeschylushadused only two), and his plays have well-developed characters andskillfullyconstructed dramatic action. Euripedes known is for his realistic style, althoughhe was notwidely appreciated in his own day. Euripides criticizedandquestioned contemporary values beliefs and by using the traditional Greekmyths andlegends. COMEDY. Comedies were humorous plays set mostly invented in situations rather thanin theworld ofmyth orlegend. Although formally added 18 DRAMA, GREEK * satire literary technique that uses wit and sarcasm to expose or ridicule vice and folly * polls in ancient Greece, the dominant form of political and social organization; a city-state to the Athenian dramatic festivals in 486 B.C., comedies probably existed long before that time. The roots of comedy may lie in religious dances or processions that included people wearing masks or disguises. The earliest surviving comedies are 11 plays by ARISTOPHANES and date from the 400s and early 300s B.C. These plays show that satire* was one of the hallmarks of early Greek comedy, also called Old Comedy Old Comedy plots were loose and fantastic, shifting wildly between locations. The chorus might be portrayed as a band of wasps, frogs, or clouds. The plays ridicule prominent citizens, local politicians, and even the gods. Some poke fun at individuals and situations that the audience would easily have recognized. By the late 300s B.C., playwrights created works in a new style called New Comedy. New Comedy plots were less fantastic and more concerned with situations arising from personal relationships. Popular subjects included romantic love, mistaken identity, and reunions of separated family members. Humor was rooted not in political or social satire but in the interactions of certain familiar characters—-the bad-tempered old man, the playboy son, the clever slave, or the boastful soldier. The best examples of New Comedy are the plays of MENANDER, the leading playwright of the 300s B.C. and a powerful influence on the Roman comic dramatists PLAUTUS and TERENCE. STAGING A PRODUCTION. In fifth-century Athens, tragedies usually had only one performance in a competition at the spring festival of Dionysus, after which a panel of citizens awarded a first, second, and third prize. In order to compete, a poet submitted his work to one of the city's chief elected officials and "asked for a chorus." If the work was accepted, this official appointed a choregos. A choregos was a wealthy citizen who agreed to pay, by way of a special tax, the most costly part of a production—the recruiting, training, maintaining, and costuming of the chorus. Poets competed with not one, but four plays (known as a tetrology), and so usually four choruses were needed. Early choruses were large, with as many as 50 members, although later choruses usually had 12 or 15 members. By acting as choregos, an individual was performing an act of public service, much as if he outfitted a warship for the polis* in time of war. While costuming the chorus was expensive, the group itself did not have to be paid. Although actors were appointed and paid separately by the polis, chorus members were amateur volunteers, drawn from the public at large. They contributed their services as a public duty, just as they contributed their time and energy to the army or in the law courts. THE THEATRICAL PERFORMANCE. Because the drama competitions were part of state-sponsored festivals, attendance was a civic duty. (Scholars still debate whether or not women were allowed to attend plays.) Outdoor theaters were large, so most of the local population could be packed into a single performance. Plays were held in daylight; there were no curtains or lights. The performance was held on a circular orchestra, or floor, with the audience seated on a hillside rising in a semicircle around the orchestra. Greek drama was a musical experience. The chorus sang, accompanied by flutes and drums. In addition, the actors sang at the emotional 19 DRAMA, GREEK THE GOD FROM THEMACHINI Greek theaters used two mechanical devices in their productions. One vm a pbtferm that cmrld te pushed or roiled out onto the stage. This platform was used for important pnsps or perhaps even for m& of tite adesls ttorn*^— such as a dying character in a tragedy—so that the audience might get a better view. The other device was a crane that swung actors through the air as If they mm flying, Gods often appeared this ww* Sonw cities acoisfd playwrights of solving difficult problems In their plots by Mug a god descend 'tb-.ttt things right The Latin phrase £/m ex mad/no [the god from the machine) still refers to a sudden, unexpected arrival or soMfoa * rhetoric art of using words effectively in speaking or writing See color plate 7, vol. 4. 20 high points of the play. Unfortunately, none of this music has been preserved. In the A.D. 1600s in Europe, the earliest composers of Italian opera fused acting and singing in the hope of reconstructing the vanished art of Greek drama. Dancing, too, played an important role in the Greek plays. The chorus danced energetically, creating a spectacle of movement that helped interpret the spoken words of the play. These dances were especially important in the largest theaters, such as the Theater of Dionysus at Athens, which held about 15,000 people. Audience members far from the stage could not see the actors' gestures, but they could follow the movements of the chorus. Besides singing and dancing, the chorus played other roles in the performance. Its members might portray a variety of characters—wise men, soldiers, people of a city, or whatever the story required. They could also step out of the action and become narrators, providing additional information about the story or helping viewers interpret what they saw. Certain aspects of Greek drama remained unchanged for centuries. For instance, men played all the parts and actors wore masks. Drama changed in other ways, however. As time went on, the chorus became smaller, and in New Comedy it almost vanished. Also, stage sets gradually became more elaborate. Early dramas were performed on a stage that was empty except for a hut or tent, and the audience sat on all sides of the stage. Later stage buildings were larger and more magnificent, with audiences sitting only in the front. Revolving panels presented different backgrounds to the audience, indicating changes of scene. Every important city had its own theater, and a few, such as the ones at SYRACUSE and EPIDAURUS, still stand today. Where no theater existed, the theatrical company performed on a portable stage. ACTORS IN ANCIENT GREECE. The early Greek playwrights often wrote, directed, and acted in their plays. They could hope to win victory wreaths and small cash prizes at drama competitions. But since it was almost impossible to earn a living as a full-time actor in early Greece, some actors also worked as teachers of rhetoric*. In a society in which the art of public speaking was highly regarded, acting was an honored profession, and a gifted actor could succeed in politics. In addition to their vocal abilities, actors had to possess considerable physical agility, and they often trained as hard as athletes did. Beginning in 449 B.C., separate prizes were awarded for actors, distinct from the awards for dramatists. The first actors' guild, or union, called the Artists of Dionysus, was formed to negotiate contracts and set standards for the profession. Prominent actors traveled from festival to festival throughout the Mediterranean, commanding huge salaries. As the number of professional actors was increasing (even chorus parts were filled by professionals), the days of the honorable amateur ended, and the status of actors in Greece slumped. However, centuries after Greece's golden age of drama in the 400s B.C., theatrical troupes continued to stage the plays of Euripides and other Greek masters. (See also Drama, Roman; Festivals and Feasts, Greek; Festivals and Feasts, Roman; Hiad\ Literature, Greek; Odyssey; Theaters.)