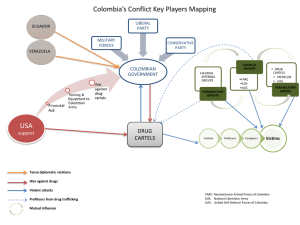

Transnational networks of insurgency and crime: explaining the

advertisement