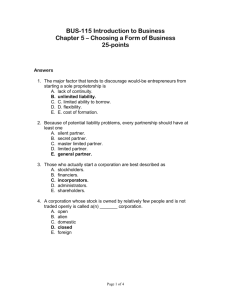

Table of Contents - Colorado Bar Association

advertisement