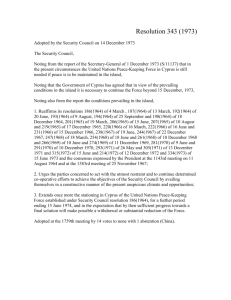

The study of the conditions under which a just and stable peace can

advertisement