ENGLISH LITERATURE TERMS

advertisement

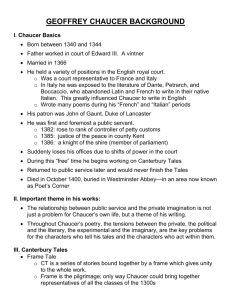

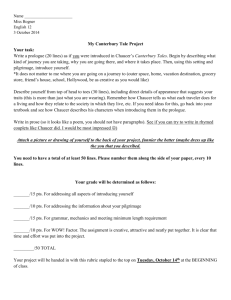

1 ENGLISH LITERATURE TERMS • abecedarian poem a poem having verses beginning with the successive letters of the alphabet. • abstract used as a noun, the term refers to a short summary or outline of a longer work. As an adjective applied to writing or literary works. Abstract refers to words or phrases that name things not knowable through the five senses. Examples of abstracts include the ‘Cliffs Notes’ summaries of major literary works. Examples of abstract terms or concepts include ‘idea’, ‘guilt’ ‘honesty’ and ‘loyalty’. • abstract language words that represent ideas, intangibles and concepts such as ‘beauty’ and ‘truth’. • abstract poetry poetry that aims to use its sounds, textures, rhythms and rhymes to convey an emotion, instead of relying on the meanings of words. • absurd theatre see theatre of the absurd. • absurdism see theatre of the absurd. • academic verse poetry that adheres to the accepted standards and requirements of some kind of ‘school’. Poetry approved, officially, or unofficially, by a literary establishment. • acatalectic a verse having a metrically complete number of syllables in the final foot. • accent 1. the emphasis or stress placed on a syllable in poetry. Traditional poetry commonly uses patterns of accented and unaccented syllables (known as feet) that create distinct rhythms. Much modern poetry uses less formal arrangements that create a sense of freedom and spontaneity. The following line from William Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’: ‘to be or not to be: that is the question’ has five accents, on the words ‘be’, ‘not’, ‘be’ and ‘that’, and the first syllable of ‘question’. 2. the rhythmically significant stress in the articulation of words, giving some syllables more relative prominence than others. In words of two or more syllables, one syllable is almost invariably stressed more strongly than the other syllables. In words of one syllable, the degree of stress normally depends on their grammatical function; nouns, verbs and adjectives are usually given more stress than articles or prepositions. The words in a line of poetry are usually arranged so the accents occur at regular intervals, with the meter defined by the placement of the accents within the foot. Accent should not be construed as emphasis. 3. the emphasis, or stress, given to a syllable in pronunciation. Accents can also be used to emphasise a particular word in a sentence. • accentual meter a rhythmic pattern based on a recurring number of accents or stresses in each line of a poem or section of a poem. • accentual verse lines whose rhythm arises from its stressed syllables rather than from the number of its syllables, or from the length of time devoted to their sounding. Old English poems such as Beowulf and Caedmon’s Hymn are accentual. They fall clearly into two halves, each with two stresses. • accentual-syllabic verse the normal system of verse composition in England since the fourteenth century, in which the meter depends upon counting both the number of stresses and the total number of syllables in any given line. An iambic pentameter for example contains five stressed syllables and a total of ten syllables. • acephalexis initial truncation (the dropping of the first, unstressed syllable at the beginning of a line of iambic or anapaestic verse). • acephalous (Greek ‘headless’) a line of verse without its expected initial syllable. • acrostic 1. a poem in which the first letter of each line spells out a name (downwards). 2. a word, phrase, or passage spelled out vertically by the first letters of a group of lines in sequence. Sir John Davies’ ‘Hymns of Astraea’ dedicates 26 acrostic poems to Elizabeth I. • act a major section of a play. Acts are divided into varying numbers of shorter scenes. From the ancient times to the nineteenth century, plays were generally constructed of five acts, but modern works typically consist of one, two, or three acts. Examples of five-act plays include the works of Sophocles and Shakespeare, while the plays of Arthur Miller commonly have a three-act structure. The ends of acts are typically indicated by lowering the curtain or turning up the houselights. Playwrights frequently employ acts to accommodate changes in time, setting, characters on stage, or mood. In many full-length plays, acts are further divided into scenes, which often mark a point in the action when the location changes or when a new character enters. • acto a one-act Chicano theatre piece developed out of collective improvisation. • adonic a verse consisting of a dactyl followed by a spondee or trochee. • adynaton a type of hyperbole in which the exaggeration is magnified so greatly that it refers to an impossibility, for example, ‘I’d walk a million miles for one of your smiles’. • aesthetic movement a literary belief that art is its own justification and purpose, advocated in England by Walter Pater and practiced by Edgar Allan Poe, Algernon Charles Swinburne and others. • aestheticism a literary and artistic movement of the nineteenth century. Followers of the movement believed that art should not be mixed with social, political, or moral teaching. The statement ‘art for art’s sake’ is a good summary of aestheticism. The movement had its roots in France, but it gained widespread importance in England in the last half of the nineteenth century, where it helped change the Victorian practice of including moral lessons in literature. Oscar Wilde is one of the best-known ‘aesthetes’ of the late nineteenth century. • affective fallacy an error in judging the merits or faults of a work of literature. The ‘error’ results from stressing the importance of the work’s effect upon the reader — that is, how it makes a reader ‘feel’ emotionally, what it does as a literary work — instead of stressing its inner qualities as a created object, or what 2 it ‘is’. The affective fallacy is evident in Aristotle’s precept from his ‘Poetics’ that the purpose of tragedy is to evoke ‘fear and pity’ in its spectators. Also known as sympathetic fallacy. • afflatus a creative inspiration, as that of a poet; a divine imparting of knowledge, thus it is often called divine afflatus. • Age of Johnson the period in English literature between 1750 and 1798, named after the most prominent literary figure of the age, Samuel Johnson. Works written during this time are noted for their emphasis on ‘sensibility’ or emotional quality. These works formed a transition between the rational works of the Age of Reason, or Neoclassical period and the emphasis on individual feelings and responses of the Romantic period. Significant writers during the Age of Johnson included the novelists Ann Radcliffe and Henry Mackenzie, dramatists Richard Sheridan and Oliver Goldsmith and poets William Collins and Thomas Gray. Also known as Age of Sensibility. • Age of Sensibility see Age of Johnson. • agrarians a group of Southern American writers of the 1930s and 1940s who fostered an economic and cultural program for the South, based on agriculture, in opposition to the industrial society of the North. The term can refer to any group that promotes the value of farm life and agricultural society. Members of the original Agrarians included John Crowe Ransom, Alien Tate and Robert Penn Warren. • alazon a deceiving or self-deceived character in fiction, normally an object of ridicule in comedy or satire, but often the hero of a tragedy. In comedy, he most frequently takes the form of a pedant. • alcaic verse a Greek lyrical meter, said to be invented by Alcaeus, a lyric poet from about 600 B.C. Written in tetrameter, the greater Alcaic consists of a spondee or iamb, followed by an iamb plus a long syllable and two dactyls. The lesser Alcaic, also in tetrameter, consists of two dactylic feet, followed by two iambic feet. • alcaics a four-line Classical stanza named after Alcaeus, a Greek poet, with a predominantly dactylic meter, imitated by Alfred lord Tennyson’s poem, Milton. • Alexandrine 1. an iambic line of twelve syllables, or six feet, usually with a caesura after the sixth syllable. It is the standard line in French poetry, comparable to the iambic pentameter line in English poetry. 2. a metrical line of six feet or twelve syllables (in English), originally from French heroic verse. Randle Cotgrave, in his 1611 French-English dictionary, explains: ‘Alexandrin. A verse of 12, or 13 syllables’. In his Essay on Criticism, Alexander Pope says, ‘A needless Alexandrine ends the song.That like a wounded snake, drags its slow length along’ (359). Examples include Michael Drayton’s Polyolbion, Robert Bridges’ Testament of Beauty and the last line of each stanza in Thomas Hardy’s The Convergence of the Twain. • allegory 1. a narrative technique in which characters representing things or abstract ideas are used to convey a message or teach a lesson. Allegory is typically used to teach moral, ethical, or religious lessons but is sometimes used for satiric or political purposes. Examples of allegorical works include Edmund Spenser’s ‘The Faerie Queene’ and John Bunyan’s ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’. 2. a figurative illustration of truths or generalisations about human conduct or experience in a narrative or description, by the use of symbolic fictional figures and actions which resemble the subject’s properties and circumstances. • alliteration a poetic device where the first consonant sounds or any vowel sounds in words or syllables are repeated. The following description of the Green Knight from the anonymous ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ gives an example of alliteration: And in guise all of green, the gear and the man: A roat cut close, that clung to his sides An a mantle to match, made with a lining Of furs cut and fitted — the fabric was noble.... • allusion a reference to a familiar literary or historical person or event, used to make an idea more easily understood. For example, describing someone as a ‘Romeo’ makes an allusion to William Shakespeare’s famous young lover in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. • ambiguity allows for two or more simultaneous interpretations of a word, phrase, action or situation, all of which can be supported by the context of a work. Deliberate ambiguity can contribute to the effectiveness and richness of a work, for example, in the open-ended conclusion to Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown. However, unintentional ambiguity obscures meaning and can confuse readers. • Amerind literature the writing and oral traditions of Native Americans. Native American literature was originally passed on by word of mouth, so it consisted largely of stories and events that were easily memorised. Amerind prose is often rhythmic like poetry because it was recited to the beat of a ceremonial drum. Examples of Amerind literature include the autobiographical ‘Black Elk Speaks’, the works of N. Scott Momaday, James Welch and Craig Lee Strete and the poetry of Luci Tapahonso. • amphibrach a metrical foot consisting of a long or accented syllable between two short or unaccented syllables. • amphigouri a verse composition, which is although apparently coherent, contains no sense or meaning. • amplification the use of bare expressions, likely to be ignored or misunderstood by a hearer or reader because of the bluntness. Emphasis through restatement with additional details. • anachronism the placement of an event, person, or thing out of its proper chronological relationship, sometimes unintentional, but often deliberate as an exercise of poetic license. • anaclasis the substitution of different measures to break up the rhythm. ENGLISH LITERATURE IMPORTANT POINTS ENGLISH LITERATURE AT A GLANCE MAIN PERIODS OF ENGLISH LITERATURE C. 450-C. 1066 Old English (or AngloSaxon) Period C. 1066-C.1500 Middle English Period C. 1500-1660 The Renaissance 1558-1603 Elizabbethan Age 1603-1625 Jacobean Age 1625-1649 Caroline Age 1649-1660 Commonwealth and Protectorate Period C. 1660-C. 1800 Neo-classical Period 1660-1700 The Restoration Age C. 1700-C.1745 The Augustan Age or The Age of Pope C. 1745-C. 1798 Age of Sensibility or The Age of Johnson C. 1798-C. 1832 Period of the Romantic Revival 1832-1901 Victorian Age 1901-1918 Edwardian Age 1918-1939 Modern Age 1939The Present Age TABLE OF THE SOVEREIGNS SINCE THE CONQUEST [1066] I. THE NORMAN KINGS 1. William I [1066-87] 2. William II [1087-1100] . 3. Henry I [1100-35] 4. Stephen [1135-54] II. PLANTAGENET KINGS 5. Henry II of Anjou [1154-89] 6. Richard I [1189-99] 7. John [1199-1216] 8. Henry III [1219-54] 9. Edward I [1272-1307] 10. Edward II [1307-27] 11. Edward III [1327-77] 12. Richard 11[1377-99] III. THE HOUSE OF LANCASTER 13. Henry IV [1399-1413] 14. Henry V [1413-22] 15. Henry VI [1422-61] IV. THE HOUSE OF YORK 16. Edward IV [1461-83] 17. Edward V [1483] 18. Richard III [1483-85] V. THE TUDOR EYNASTY 19. Henry VII [1461- 1509] 20. Henry VIII [1509-47] 21. Edward VI [1547-53] 22. Mary [1553-58] 23. Elizabeth I[1558-1603] VI. THE STUART DYNASTY 24. James I [1603-25] [Commonwealth [1689-1702]; Protectorate (1653-60)] 25. Charles I (1625-49) 26. Charles II (1660-85 27. James II (1685-88) 28. William and Mary (1689-1702) 29. Anne (1702-14) VII. THE HOUSE OF HANOVER 30. George I (1714-27) 31. Geroge II (1727-60) 32. George III (1760-1820) 33. Geroge IV (1727-60) 34. William IV (1831-37) 35. Victoria (1837-1901) 36. Edward VII (1901-10) 37. George V (1910-36) 38. Edward VIII (1936) 39. George VI (1936-52) 40. Elizabeth II (1952-) 3 ENGLISH LITERATURE AT A GLANCE THE AGE OF CHAUCER (1340-1400) POETRY Geoffrey Chaucer (1340-1400) The Romaunt of the Rose (1360-65?); The Book of the Duchesse (1369); The Parlement of Foules; Troilus and Criseyde (1379-83); The House of Fame (1383-84); The legend of Good Women (1385-86); The Canterbury Tales (1386 onward). William Langland (1330-1386) The Vision of william Concerning Piers the Plowman (1362 90). John Gover (?1330-84) Speculum Meditantis(1378?), Vox Clamantis(1382), Confessio Amantis(1390) John Barbour (1320-95) Bruce(1375). PROSE Sir John Mandeville (died 1372) Mandeville’s Travels (1356). John Wycliffe (1320-84) Wycliffe’s Bible (1380). Sir Thomats Malory (died 1471) Le Morte D’ Arthur (1469). FROM CHAUCER TO ‘TOTTLE’S MISCELLANY’ (1400-1557) POETRY Geoffrey Chaucer(1340-1400) The Tale of Melibeus, The Parson’s Tale. James I (1394-1437) The King’s Quair (1423-1424). Sir David Lyndsay (1458-1555) The Dreme(1528), The History of Squyer Meldrum(1549), The Testment and Compleynt of the Papyngo,(1530), Satyre of the Thire Estaitis(1540). Robert Henryson(1430-1506) Lament for the Makaris (1508), The Testament of cresseid (1593), Orpheus and Eurydice; Robene and Makyne; Garmond Qf Gude Ladies. William Dunbar(?1456-?1513) The Goldyn Targe (1503), The Dance of the Sevin Deidlie Synnis (1503-1508), Tua Mariit Women and the Wedo (1508), Lament for the Makaris (1508). Gawin Douglas(?1474-1552) The Palice of Honour (1501),published (1533),King Hart (first printed 1786). John Skelton(?1460-1529) Garlande of laurell (printed 1523),Dirge on Edward Iv, The Bowge of Court(1499). John Lydgate(1370-1451) ‘Iroy Book (1412-1420), The Falls of Princes(1430-1438), The Temple of Glass; The Story of Thebes(1420), London Lickpenny. Thomas Occleve(1368?-1450?) The Regement of Princes (1411-12), La Male Regle (1406); The Complaint of Our Lady, Occleve’s Complaint. Stephen Hawes (?1474-1530) The Passtyme of Pleasure (1509), The Example of Virtue (1512), The Conversion of Swerers; A Joyfull Medytacyon. Alexander Barclay (?1475-1552) Ship of Fools (1509), Certayne Ecloges (1515). PROSE Reginald Pecock (?1390-?1461) 4 The Repressor of over-much Blaming of the Clergy (1455), The Book of Faith (1456). Willism Caxton (?1422-91) Recuyell of the Historie of Troye(1471), (?1422-91) Game and Playe of the the chesse (1475), The Dictes and Sayengis of the Philosphers (1477). John Fisher (1459-1535) Tracts and sermons; The Ways to Perfect Religion. Hugh Latimer (?1485-1555) Sermons (1562). Sir Thomas More (1478-1535) Utopia (1516); The Lyfe of John Picus (1510), The Historie of Richard III (1543). Sir Thomas Elyot (?1478-1535) The Boke named the Governour (1531), The Doctrine of Princes (1534) John Capgrave (1393-1464) The Chronicle of English History extending to A. D. 1417. Sir John Fortescue (?1394-?1476) On the Govenance of England, A Delcaration upon Certain Wrytinges (1471-73). DRAMA John Heywood (?1494-?1580) The Four p’s (?1545), Play of the Wether (1533), A Play of Love (1433). Thomas Norton (1532-84) and T. Sackville (1536-1608) Gorboduc (1561). Thomas Preston (1536-1608) A Lamentable Tragedy mixed full of Mirth Containing the life of Cambyses, King of Percia (1569). WIlliam Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle (1562). Nicholas Udall (1505-56) Ralph Roister Doister (written 1553, published 1567) THE ELIZABETHAN AGE (1558-1603) THE JACOBEAN AGE (1603-1625) THE AGE OF SHAKESPEARE (15581625) POETRY George Gascoigne (?1525-77) Jocasta Jocasta (1566), Supposes (1566). Edmund Spenser (1552-99) The Shepherds Calendar (1579), Mother Hubberd’s Tale (1591), The Ruins of Rome (1591), Amoretti (1595); Epithalamion; Colin Clout Comes Home Again (1595), Four Hymns (1596), Prothalamion (1596), The Faerie Queene (Book I-III, 1589, IV, 1596). John Donne (1573-1631) Satires (1590-1601), The Songs and Sonnets (1590-1601), The Elegies (1590-1601), Of the Progress of the Soule (1601) Holy Sonnets (1617). Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-42) In Tottel’s Miscellany (1557), Included in Songs and Sonnetts (1557) ed.Tottel. Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517-47) Certain Bokes of Virgiles Aeneis turned into English Meter (1557)his poems; in Tottle’s Miscellany (1557). Thomas Sackville (1536-1608) The Induction (1563), The Complayment of Henry, Duke of Buckingham, (1563). George Gascoigne (1534-77) The Steele Glas, A Satyre (1576) Sir Philip Sidney (1554-86) Astrophel and Stella (1591). Michael Drayton (1563-1631) The Harmonie of the Church (1591), Englnad’s Heroicall Epistles (1597), The Baron’s Wars (1603), Polyolbion (1622), . Nymphida (1627). Thomas Campion (1567-1620) A Book of Ayreas (1601), Songs of Mourning (1613), Two Books of Ayres (1612). Phineas Fletcher (11582-1650) The Purple Island, of The Isle of Man (1633). Giles Fletcher (11588-1623) Chirst’s Victorie and Triumph (1610). Samuel Daniel (1562-1619) Delia (1592), The Complaynt of Rosamond (1592), The Civil Wars (1595). William Shakespeare (1564-1616) The Rape of Lucrece (1594), Venus and Adonis (1593). A Collection of Sonnets, (1609), The Passionate Pilgrim (1599). DRAMA George Peele (1558-98) The Araygnement of Paris (1584), The Famous Chronicle of King Edward the first (1593), The Old Wives’ Tale (159194). The Love of King David and Fair Bathsabe (1599). Robert Greene (1558-92) Alphonsus, King of Aragon (1587), Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (1589), Orlando Furioso (1591), The Scottish Historie of James of Fourth (1592). Thomas Nashe (1567-1611) Summer’s Last Will and Testament (1592). John Lyly (11554-1606) Alexander and Campasye (1584); Endymission (1591), Midas (1592), The Woman in the Moon (1597) Thomas Lodge (1558-1625) Henry VI (1591-92), The Woundes of Cicil War, Rosalynde, Euphues Golden Legcie (A Romance) (1590), Scillaes Metamorphosis (1589). Thomas Kyd (1558-94) The Spanish Tragedy (1585), Cornelia (1593), Soliman and Perseda (1588), First Part of Jernimo (1592). Christopher Marlowe (1564-93) Tamberlaine the Great (1587), The Second Part of Tamberlaine the Great (1588), Edward II (1591), The Jew of Malta (1589, Docator Faustus (1592), The Tragedy of Dido, Qween of Carthage (1593). The Massacre of Paris (1593). William Shakespeare (1564-1616) 1. Henry VI (1591-92) 2. Henry VI (1591-92), 3. Henry VI (1591-92), Richard III (1593), The Comedy of Errors (1593), Titus Andronicus (1594), The Taming of The Shrew (1594), Love’s Labour’s Lost (1594), Romeo and Juliet (1594), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595), The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1595), King John (1595), Richard II (1596) The Merchant of Venice (1596), Henry IV (1598),Much Ado About Nothing(1598), Henry V (1599), Julius Caesar (1599),The Merry Wives of Winsor (1600), As you Like It (1600), Hamlet (1601), Twelfth Night (1601), Troilus and Cressida (1602), All’s Well that Ends well (1602), Measure for Measure (1604), Othello (1604), Macbeth (1605), King Lear (1605), Antony and Cleopatra (1606), Coriolanus Timon of Athens (1607), Pericles (1608), Cymbeline (1609), The Winter’s Tale (1610), The Tempest (1611), Henry VIII (in part) (1613). 5 INDIAN WRITERS IN ENGLISH SRI AUROBINDO Sri Aurobindo (Sri Orobindo) (August 15, 1872-December 5, 1950) was an Indian nationalist, scholar, poet, mystic, evolutionary philosopher, Yogi and spiritual Guru. After a short political career in which he became one of the leaders of the early movement for Indian independence from British rule, Sri Aurobindo turned to the exploration of the subtle realms of human existence and, as a consequence, developed a new spiritual path which he termed Integral Yoga. The Times Literary Supplement wrote of Aurobindo: “In fact, he is a new type of thinker, one who combines in his vision the alacrity of the West with the illumination of the East. To study his writings is to enlarge the boundaries of one’s knowledge... He is a yogi who writes as though he were standing among the stars, with the constellations for his companions”. The central theme of Sri Aurobindo’s vision is the evolution of life into a “life divine”. In his own words: “Man is a transitional being. He is not final. The step from man to superman is the next approaching achievement in the earth’s evolution. It is inevitable because it is at once the intention of the inner spirit and the logic of Nature’s process”. The principal writings of Sri Aurobindo include: The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Secrets of the Vedas, Essays on the Gita, The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, Renaissance in India and other essays, Supramental Manifestation upon Earth, The Future Poetry, Thoughts and Aphorisms, Savitri, several volumes of letters, and the collected poems. EARLY LIFE Sri Aurobindo was born Aurobindo Ghose, pronounced and often written as “Ghosh” (or “Arabindo Ghosh”), in Kolkata (Calcutta), India, on 15th August, 1872. Aravind means Lotus (pronounced “Aurobindo” in Bengali). His father was Dr K. D. Ghose and his mother Swarnalata Devi. Dr. Ghose (who had lived in Britain and studied medicine at Aberdeen University), was determined that his children should have an English education free of any Indian influences. He therefore sent the young Aurobindo and his siblings to the Loreto Convent school in Darjeeling. Subsequently, at the age of seven, Aurobindo was taken (along with his two elder brothers Manmohan and Benoybhusan) to Manchester, England and placed in the care of a Mr and Mrs. Drewett—an Anglican clergyman and his wife—who tutored Aurobindo privately. Mr. Drewert, himself a capable scholar, grounded Aurobindo so well in Latin that Aurobindo was able to gain admission into St Paul’s School in London. At St. Paul’s Aurobindo learned Greek and Latin. The last three years at St Paul’s were spent in reading literature, especially English Poetry. At St. Paul’s he received the Butterworth Prize for literature, the Bedford Prize for history and a scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge University. He returned to India in 1893. During the First Partition of Bengal from 1905 to 1912, he became a leader of the group of Indian nationalists known as the Extremists for their willingness to use violence and advocate outright independence, a plank more moderate nationalists had shied away from up to that point. He was one of the founders of the Jugantar party, an underground revolutionary outfit. He was the editor of a nationalist Bengali newspaper Vande Mataram (spelt and pronounced as Bonde Matorom in the Bengali language) and as a result came into frequent confrontation with the British Raj. In 1907 he attended a convention of Indian nationalists where he was seen as the new leader of that movement. It was at this point that Rabindranath Tagore paid him a visit and wrote the lines: “Rabindranath, O Aurobindo, bows to thee! O friend, my country’s friend, O Voice incarnate, free. Of India’s soul....The fiery messenger that with the lamp of God Hath come...Rabindranath, O Aurobindo, bows to thee”. CONVERSION FROM POLITICS TO SPIRITUALITY His conversion from political action to spirituality occurred gradually, first at Vadodara (then Baroda) under the spiritual instruction of a Maharashtrian Yogi called Vishnu Bhaskar Lele, and second, while awaiting trial as a prisoner in Alipore Central Jail (in Kolkata in the province of Bengal). Here his study and practice of the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita led to a number of mystical experiences. Sri Aurobindo claimed to have been visited in his meditations by the renowned Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu philosopher of great importance to Advaita Vedanta, who guided Sri Aurobindo in an important aspect of his spiritual practice or yoga. Sri Aurobindo later said that while imprisoned he saw the convicts, jailers, policemen, the prison bars, the trees, the judge, the lawyers as different forms of Vishnu in the spiritual experience of Vasudeva. The subsequent trial involving Aurobindo was one of the defining moments in the Indian nationalist movement. There were 49 accused and 206 witnesses, 400 documents were filed and 5000 exhibits produced—including bombs, handguns and acid. The English judge, C.P. Beachcroft, turned out to have been a student with Sri Aurobindo at Cambridge. The Chief Prosecutor Eardley Norton displayed a loaded revolver on his briefcase during the trial. The case for Sri Aurobindo was taken up by Chittaranjan Das who said in his conclusion to the Judge: My appeal to you is this, that long after the controversy will be hushed in silence, long after this turmoil, this agitation will have ceased, long after he (Sri Aurobindo) is dead and gone, he will be looked upon as the poet of patriotism, as the prophet of nationalism and lover of humanity. Long after he is dead and gone, his words will be echoed and re-echoed, not only in India, but across distant seas and lands. Therefore, I say that the man in his position is not only standing before the bar of this Court, but before the bar of the High Court of History. The trial (“Alipore Bomb Case, 1908”) lasted for one full year, but eventually Sri Aurobindo was acquitted. Afterwards Aurobindo started two new weekly papers: the Karmayogin in English and the Dharma in Bengali. However, it appeared that the British government would not tolerate his nationalist program as Lord Minto wrote about him: “/ can only repeat that he is the most dangerous man we have to reckon with.” Sought again by the Indian police, he was guided to the French settlements, and on April 4, 1910 he finally found refuge with other nationalists in the French colony of Pondicherry. PHILOSOPHICAL AND SPIRITUAL WRITINGS In 1914, after four years of concentrated yoga at Pondicherry (now Puducherry), Sri Aurobindo launched Arya, a 64 page monthly review. For the next six and a half years this became the vehicle for most of his most important writings, 6 which appeared in serialised form. These included The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Essays on The Gita, The Secret of The Veda, Hymns to the Mystic Fire, The Upanishads, The Foundations of Indian Culture, War and Self-determination, The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, and The Future Poetry. Sri Aurobindo however revised some of these works before they were published in book form. Somewhat later, he wrote a small book entitled The Mother which was published in 1928 as a kind of “instruction manual” for the practice of Integral Yoga. In this short book, Sri Aurobindo wrote about the Divine Mother, the consciousness and force of the Supreme, and about the “Four great Aspects of the Mother, four of her leading Powers and Personalities (which) have stood in front in her guidance of the Universe and her dealings with the terrestrial play...” He also wrote about the conditions to be fulfilled by the “Sadhaka” or practitioner of the yoga in order to be receptive to the Mother’s Grace. He explained his view of money and wealth: “Money is a sign of universal force, and this force in its manifestation on earth works on the vital and physical planes and is indispensable to the fullness of outer life. In its origin and its true action it belongs to the Divine. But like other powers of the Divine it is delegated here and in the ignorance of the lower Nature can be usurped for the uses of the ego or held by Asuric influences and perverted to their purpose.” For some time afterwards, Sri Aurobindo’s main literary output was his voluminous correspondence with his disciples. His letters, most of which were written in the 1930s, numbered in the several thousands. Many were brief comments made in the margins of his disciple’s notebooks in answer to their questions and reports of their spiritual practice—others extended to several page carefully composed explanations of practical aspects of his teachings. These were later collected and published in book form in three volumes of Letters on Yoga. In the late 1930s, Sri Aurobindo resumed work on a poem he had started earlier—he continued to expand and revise this poem for the rest of his life. It became perhaps his greatest literary achievement, Savitri, an epic spiritual poem in blank verse of approximately 24,000 lines. Although Sri Aurobindo wrote most of his material in English, his major works were later translated into a number of languages, including the Indian languages Hindi, Bengali, Oriya, Gujarati, Marathi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, as well as French, German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, Chinese, Portuguese, Slovene and Russian. A large amount of his work in Russian translation is also available online. THE MOTHER Sri Aurobindo’s close spiritual collaborator, Mirra Richard (b. Alfassa), was known as The Mother. She was born in Paris on February 21, 1878, to Turkish and Egyptian parents. Involved in the cultural and spiritual life of Paris, she counted among her friends Alexandra David-Neel. She went to Pondicherry on March 29, 1914, finally settling there in 1920. Sri Aurobindo considered her his spiritual equal and collaborator. After November 24, 1926, when Sri Aurobindo retired into seclusion, he left it to her to plan, run and build the growing Sri Aurobindo Ashram, the community of disciples that had gathered around them. Some time later when families with children joined the ashram, she established and supervised the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education (which, with its pilot experiments in the field of education, impressed observers like Jawaharlal Nehru). When Sri Aurobindo died in 1950, the Mother continued their spiritual work and directed the Ashram and guided their disciples. In the mid 1960s she started Auroville, an international township sponsored by UNESCO to further human unity near the town of Pondicherry, which was to be a place “where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities.” It was inaugurated in 1968 in a ceremony in which representatives of 121 nations and all the states of India placed a handful of their soil in an urn near the center of the city. Auroville continues to develop and currently has approximately 1700 members from 35 countries. The Mother also played an active role in the merger of the French pockets in India and, according to Sri Aurobindo’s wish, helped to make Pondicherry a seat of cultural exchange between India and France. The Mother stayed in Pondicherry until her death on November 17,1973. Her later years —including her myriad of metaphysical and occult experiences, and her attempt at the transformation of her body—are captured in her 13 volume personal log known as Mother’s Agenda. GOING BEYOND HINDU PHILOSOPHY AND VISION One of Sri Aurobindo’s main philosophical achievements was to introduce the concept of evolution into Vedantic thought. Samkhya philosophy had already proposed such a notion centuries earlier, but Aurobindo rejected the materialistic tendencies of both Darwinism and Samkhya, and proposed an evolution of spirit along with that of matter, and that the evolution of matter was a result of the former. He describes the limitation of the Mayavada of Advaita Vedanta, and solves the problem of the linkage between the ineffable Brahman or Absolute and the world of multiplicity by positing a transitional hypostasis between the two, which he called The Supermind. The supermind is the active principle present in the transcendent Satchidananda; a unitary mind of which our individual minds and bodies are minuscule subdivisions. Sri Aurobindo rejected a major conception of Indian philosophy that says that the World is a Maya (illusion) and that living as a renunciate was the only way out. He says that it is possible, not only to transcend human nature but also to transform it and to live in the world as a free and evolved human being with a new consciousness and a new nature which could spontaneously perceive truth of things, and proceed in all matters on the basis of inner oneness, love and light. EVOLUTIONARY PHILOSOPHY Sri Aurobindo argues that humankind as an entity is not the last rung in the evolutionary scale, but can evolve spiritually beyond its current limitations associated with an essential ignorance to a future state of supramental existence. This further evolutionary step would lead to a divine life on Earth characterized by a supramental or truth-consciousness, and a transformed and divinised life and material form. There are parallels between Sri Aurobindo’s vision and that of Teilhard de Chardin. ENGLISH LITERATURE-NET PAPER-III (A) (CORE GROUP) 1.BRITISH LITERATURE FROM CHAUCER TO THE PRESENT DAY 2.CRITICISM AND LITERARY THEORY UNIT-I LITERARY COMPREHENSION (WITH INTERNAL CHOICE OF POETRY STANZA AND PROSE PASSAGE) UNIT-II UP TO THE RENAISSANCE UNIT-III JACOBEAN TO RESTORATION PERIODS UNIT-IV AUGUSTAN AGE: 18TH CENTURY LITERATURE UNIT- V ROMANTIC PERIOD UNIT-VI VICTORIAN AND PRE-RAPHAELITES UNIT-VII MODERN BRITISH LITERATURE UNIT-VIII CONTEMPORARY BRITISH LITERATURE UNIT-IX LITERARY THEORY AND CRITICISM UP TO T.S. ELIOT UNIT-X CONTEMPORARY THEORY PAPER-II 1. CHAUCER TO SHAKESPEARE 2. JACOBEAN TO RESTORATION PERIODS 3. AUGUSTAN AGE: 18TH CENTURY LITERATURE 4. ROMANTIC PERIOD 5. VICTORIAN PERIOD 6. MODERN PERIOD 7. CONTEMPORARY PERIOD 8.AMERICAN AND OTHER NON-BRITISH LITERATURES 9. LITERARY THEORY AND CRITICISM 10. RHETORIC AND PROSODY 7 HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURY GEOFFREY CHAUCER (1340-1400) Geoffrey Chaucer (1340-1400} is one of the greatest poets of England. He is known as the ‘father of English poetry.’ This does not mean that there was no poetry or poets in England before him. But before Chaucer there was no national language; there were merely a number of regional languages. Chaucer used one of these languages-the East Midland-and by the force of his genius raised it to the level of the national language of England. He was, therefore, both the father of English poetry as well as the father of the English language. He is the first national poet of England. There were other poets also such as John Gower and William Langland. But their poetry is little read and enjoyed today, while Chaucer continues to be as fresh and enjoyable as when he lived and wrote. Chaucer’s chief works are-The Book of the Duchess; The Parliament of Fowls; The House of Fame; Troilus and Cresseyde : Legend of Good Women, and The Canterbury Tales. “THE CANTERBURY TALES” The Canterbury Tales, the greatest work of Chaucer, is a collection of stories fitted into a general frame-work which serves to hold them together. A number of pilgrims meet at the Tabard Inn in Southwark, near Canterbury in England, where the poet himself is also staying at the time; and as he too is going on the same pilgrimage, he is easily persuaded to join the party. One of the favourite places of pilgrimage is the shrine of St. Thomas a Becket at Canterbury; and to it these particular pilgrims are bound. The jolly host of the Tabard Inn, Harry Bailly, gives them hearty welcome and a good supper and, after they are satisfied, he makes three proposals: that to pass the time each member of the party shall tell two tales on the way to Canterbury, and two on the way back: that he himself shall be the judge; and that the one who tells the best tale shall be treated by all the rest to a supper on their return. The suggestion is warmly welcomed, and The Canterbury Tales is the result. All this is explained in the Prologue: after which Chaucer proceeds to introduce his fellow pilgrims. Though limited to what we may broadly call the middle classes, the company is still quite representative of the various ranks and professions of the time. In his descriptions of the most prominent of these people, Chaucer’s powers are shown at their very highest. All the characters are individualised, yet their thoroughly typical quality makes them representatives of men and manners in the England of his time. As according to programme each of the pilgrims was to have told four stories, the poet’s plan was a very large one. He lived to complete a small portion only, for the work, as we have it, is merely a fragment of twenty-four tales. Yet even as it stands its interest is wonderfully varied, for Chaucer is guided by a sense of dramatic propriety and so the tales differ in character as widely as do those by whom they are told. The tales are not original in theme. Chaucer takes his raw material from many different sources, and the range of his reading and his quick eye for anything and everything which would serve his purposes wherever he found it, are shown by the fact that he lays all sorts of literature, learned and popular, Latin, French and Italian, under contribution. But whatever he borrows he makes entirely 8 his own, and he remains one of the most delightful story tellers in verse. CHAUCER AS THE EARLIEST OF THE GREAT MODERNS Chaucer has been called the father of English poetry and E. Albert calls him “The earliest of the great moderns.” Chaucer stands at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern age. He has been called “The Morning Star of the Renaissance.” His poetry reflects the medieval spirit as well as that of the Italian Renaissance which was making its first influence felt in England in his age. There can be no greater tribute to his genius than the fact that, for the next one hundred and fifty years, there was none to match him and that he is enjoyed with the same enthusiasm today, despite the lapse of five centuries, during which time the English language has undergone radical changes. He stands head and shoulders above his contemporaries and successors. (a) His Realism Chaucer’s modernism is best reflected in his realism. He reflects the real life of the England of his day. He began his career with following the tradition of courtly love, allegory and dream poetry. But he soon discarded these traditions and turned his eyes to the life and people of his times. In his Canterbury Tales Chaucer comes to his own. His Prologue is an epitome of 14th century England. With great force and realism he has painted the life and people of his times. His realism is nowhere seen to better advantage than in the delineation of character. A.C. Ward says, “Chaucer is the first great painter of character.” With a few deft touches he brings his characters to life. They are individuals as well as types. In his twenty-nine pilgrims, all the different classes, peoples and professions of his time find a vivid expression. He represents his age not in fragments but as a whole. (b) The Renaissance Note Just as Chaucer rejected the medieval poetic tradition, so also he broke free from the religious influences of the Middle Ages. Ecclesiastical ideas and medieval habits of mind were still the controlling elements in Chaucer’s period, but in him poetry their sway is broken by the spirit of Italian Renaissance. He is the “Morning Star of the Renaissance.” “It is through him that its free, secular spirit first expresses itself in English poetry.” He loves human nature, including all its weaknesses, and takes a frank joy in the good things of life. He takes interest in his follow men, enjoys their company and is not repelled even by the wicked, the foolish, and the rascal. He is aware of the corruption in the church, but nowhere lashes at it fiercely as does Langland, his great contemporary. His wide sympathy, gentle humanity, tolerance, etc., make him really the first of the great moderns. (c) His Humour Chaucer is the first true humorist in English literature. His humour is the expression of his joy in life and of his wide sympathy and tolerance. Humour is also present in the predecessors and contemporaries of Chaucer. But in them we find only occasional and fitful flashes of humour. Humour is the life and soul of Chaucer’s works. His humour is manysided and all-pervasive, like that of Shakespeare or Dickens. His eyes take on a merry twinkle as they fall on folly or wickedness of human nature. He is a true humorist, for he has the capacity to laugh even at his own expense. He never lashes bitterly at folly or vice, but ever looks on and smiles. He is the first of the great modern humorists of England. (d) Chaucer as the Maker of Modern English Chaucer is the first great national poet of England. By freeing himself from foreign influences and by using his own native language as the medium for his art, he became the founder of modern English poetry. While even in his own age poets like Gower, used Latin and French, he concentrated his energies on the development of his native tongue and made it a fit medium for literary expression. Lowel rightly estimates Chaucer’s greatness in this respect and says, “He found English a dialect and left it a language.” While all others poets of his age were local or provincial, he alone is national. He imparted to the English language the modern ease, suppleness, flexibility and smoothness and breathed into it a high poetic life. He is certainly what Spenser called him, “The well of English undefiled.” He is the first national poet of England, for he gave to the people a language, so reformed and reshaped, as to be a potent instrument for the expression of thought. (e) The Modern Note in Chaucer’s Versification Chaucer is one of the most musical of English poets. His English looks very difficult at first, but it can easily be mastered with a little labour and perseverance. He struck a modern note when he abandoned altogether the Old English irregular lines and alliteration and adopted the French method of regular metre and end rhymes. Estimating his contribution to English verification W.H. Hudson writes, “Under his influence rhyme gradually displaced alliteration in English poetry.” He discarded complicated stanza forms and for the first time, in his verse, achieved that union of simplicity and freedom which is the characteristic note of modern English poetry. “The Heroic Couplet he introduced into English verse; the Rhyme Royal he invented.” His claim on our gratitude is two fold: first, for discovering the music that is in English speech and secondly, for his influence in fixing the East Midland dialect as the literary language of England.” (f) The Modernism of Chaucer Chaucer’s realism, his characterization, his humour, his rejection of medieval conventions, his zest for life, and last but not least, his services to the English language and versification - all entitle him to be called “the earliest of the great moderns.” When we enter his world we feel entirely at home as much as we do with Spenser, Shakespeare, or anyone of the other great luminaries of modern English literature. Chaucer is a modern who can be enjoyed by us with perfect ease. 9 ENGLISH LITERATURE UNIT - 1 AN OBJECTIVE APPROACH TO ENGLISH LITERATURE FROM CHAUCER TO MILTON 1.Who called Chaucer -”The Father of English Poetry?” (a) Spenser (b) Sidney (c) Arnold (d) None of these 2. The dialect that Chaucer used was... (a) East Midland (b) Northern Dialect (c) Both V and V (d) None of these 3. The total number of the pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales is... (a) 29 (b) 30 (c) 31 (d) 39 4.The name of the fictional inn where the pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales met is... (a) Tabard (b) Canterbury (c) Southwark (d) None of these 5.What is the reward suggested by Harry Baily, the host of the pilgrims and judge of the stories, for the best story told by the Pilgrims? (a) The best story teller was to .be made the Poet Laureate (b) The rest of the Pilgrims were to offer a supper. (c) No reward (d) None of these 6. Who is Lowea talking about in the following line? “He found English a dialect and left it a language.” (a) Shakespeare (b) Milton (c) Chaucer (d) T. S. Eliot 7. Who described Chaucer as “The Well of English undefiled”? (a) Pope (b) Dryden (c) Shakespeare (d) Spenser 8.What quality of Chaucer does the phrase “The Well of English Undefiled” refer to? (a) His diction. (b) His linguistic competence. (c) His avoidance of foreign influences. (d) None of these 9.Who introduced the heroic couplet into English? (a) Chaucer (b) Pope (c) Spenser (d) None of these 10.Why is Chaucer known as “The earliest of the great moderns”? Because of his (a) Realism (b) Humour (c) Rejection of Medieval conventions (d) All the three 11.Why did W.J. Long call Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, “The Prologue to modern fiction”? Because of its (a) Lack of Poetic Quality (b) Narrative unity (c) Formlessness (d) None of these 12.According to Arnold, what is lacking in Chaucer? (a) Good Language (b) High Seriousness (c) The Touch Stone (d) The Lyric Quality 13.Who was the poet that lived during the periods of Edward II, Richard II and Henry IV? (a) Shakespeare (b) Lovelace (c) Spenser (d) None of these 14.Who was known as Morning Star of Reformation? (a) John Wycliff (b) Langland (c) Pope John Paul (d) None of these 15.Which is the month in which groups of pilgrims used to march towards the Canterbury? (a) January (b) March (c) April (d) None of these 16.Who is the twentieth century poet that alluded to ‘April’ in one of his poems? (a) W. H. Auden (b) Ezra pound (c) W. B. Yeats (d) T. S. Eliot 17.Arnold’s Judgement of Chaucer is that Chaucer was (a) A great classic (b) Not as great as the classisists (c) As great as the classisists (d) None of these 18. Lollards are the followers of Protestant and Reformation leader? (a) John Wycliffe (b) King Edward (c) Martin Luther King (d) Martin Luther 19. Who was the first translator of the Bible into English? (a) Chaucer (b) Sir Thomas Malory (c) John Wycliff (d) None of these 20. Which version of the Bible did Wycliff make use of for the translation? (a) Greek (b) Latin (c) French (d) None of these 21. The War of the Roses’took place during... (a) 1555-85 (b) 1466-95 (c) 1455-85 (d) None of these 22. Why is The War of the Roses’ known by that name...? (a) Roses were the cause of the War. (b) The Rose was the national flower of England. (c) The two rival factions had roses (red and white) as their symbols. (d) None of these 23. Valentine and Proteus are? (a) The proponents of puritanism. (b) Originators of the Morality play. (c) The Gentlemen in the Two Gentlemen of Verona (d) None of these 24. William Caxton printed History of Troy—the first book in English in the year... (a) 1575 (b) 1550 (c) 1440 (d) 1474 25. Who was the first translator of Virgil’s works into English? (a) John Dryden (b) Chaucer (c) Gawin Douglas (d) None of these 26. Henry Vaughan was influenced by... (a) Donne (b) Thomas Carew (c) Crashaw (d) George Herbert 27.Romantic Movement had its antecedents in... (a) The Poetry of Chaucer (b) Shakespearean Comedy (c) The 15th Century ballad (d) None of these 28.Who wrote the following—”Stone walls do not a prison make/Nor iron bars a cage.” (a) Richard Lovelace (b) Robert Herric (c) Abraham Cowley (d) Thomas Carew 29. Who first employed the Blank Verse? (a) Sackville (b) Norton (c) Both a and b’ (d) None of these 30.Who is the proponent of the geocentric theory? (a) Ptolemy (b) Copernicus (c) Galileo (d) None of these 31.Whom did Legouis criticise as one who writes 10 “Charming verses on nothing”? (a) Marvel (b) John Suckling (c) John Senlam (d) Edmund Waller 32. Which poet expressed surprise at his having loved one woman “Three whole days together? (a) Suckling (b) John Donne (c) D’Avenant (d) None of these 33. Henry VII, the patron of education came to the throne in... (a) 1485 (b) 1414 (c) 1458 (d) None of these 34. Thomas More’s Utopia was published in... (a) 1551 (b) 1316 (c) 1613 (d) 1516 35. Utopia appeared in English translation in the year... (a) 1551 (b) 1516 (c) 1515 (d) None of these 36. ...is described as “The true prologue to the Renaissance”. (a) The Prince (b) Utopia (c) Poetics (d) None of these 37. Cromwell, the dictator, was said to have been influenced by... (a) Utopia (b) The Capital (c) The Prince (d) None of these 38. Calvin was a... (a) French Reformer (b) Literary writer (c) King of England (d) None of these 39. Book of Martyrs, which is about the killings by the Catholic Queen Mary, was written by... (a) Calvin (b) George Foxe (c) Pope (d) None of these 40. Which of the following Catholic dictator was succeeded by his/her step sister, Elizabeth? (a) Edward II (b) Henry IV (c) Mary (d) None of these 41.The Kingdom of Nowhere ia the other name of... (a) Utopia (b) The Prive (c) Mort d’Arthur (d) None of these 42. Match the following works with their writers (a) Ship of Fools(1) Geoffrey Chaucer (b) The Parliament (2)William Dunbar of Fowles (c) Dance of the Seven (3) John Lydgate Deadly Sinnis (d) The Temple of Glass (4)Stephen Hawes (e) The Passetyme of (5)Alexander Banklony Pleasure 43. Which of the following wrote plays that are all tragedies? (a) Shakespeare (b) Marlowe (c) Thomas Dekkar (d) None of these 44. Who wrote “Donne for not keeping of accent deserved hanging”? (a) Samuel Johnson (b) BenJonson (c) Arnold (d) T.S. Eliot 45. Who headed the Puritan Government that was formed after the hanging of Charles I ? (a) Cromwell (b) James II (c) Charles II (d) None of these 46. Who wrote the following about Milton? “...he is admirable as Virgil or Dante and in this respect he is unique among us. None else in English literature possess the like distinction”: (a) Coleridge (b) T.S. Eliot (c) Arnold (d) None of these 47. Which the following begins with this line? “If Music be the food of love, play on.” (a) The Tempest (b) All is Well that Ends Well (c) Twelfth Night (d) None of these 48. Out of the twenty complete and four incomplete stories of Chaucer, what is common between Tale ofMelibensand The Parson’s Tale? (a) These Tales were told by Chaucer himself (b) They do not figure in The Canterbury Tales (c) These two are the only tales told in prose (d) None of these 49. Name the story that Chaucer told during the pilgrimage (a) Tale of Melibens (b) The Parson’s Tale (c) He did not tell a story (d) None of these 50. Arnold wrote, “With him is born our real poetry” Who does “him” refer to? (a) Spenser (b) Shakespeare (c) Chaucer (d) Wordsworth 51.Arnold, in his The Study of Poetry, estimated Chaucer in terms of (a) ‘Historical estimation’ (b) ‘Personal estimation (c) ‘Real estimation’ (d) None of these 52. What does Shakespeare refer to in these lines? “This royal throne of kings; this sceptred isle This earth of Majesty, this seat of Mars This other Eden, demi paradise.” (a) Denmark (b) London (c) England (d) France 53. The hero in Spenser’s Faerie Queene is... (a) Prince Arthur (b) Arthur Hallam (c) Prince Charles (d) None of these 54. Spenser is known as the ‘Poets’ poet’. Who called him so? (a) Matthew Arnold (b) Sir Philip Sidney (c) Charles Lamb (d) Hazlitt 55. In which of his poems did Spenser celebrate his love? (a) The Tears of the Muses (b) Epithalamion (c) Prothalamion (d) Amoretti 56.Spenser wrote a poem in honour of his marriage. Identify it. (a) Epithalamion (b) The Faerie Queene (c) The Ruins of Time (d) None of these 57. Spenser wrote a preface to The Faerie Queene, in the form of a letter. Who is this letter addressed to? (a) John Donne (b) Sir Walter Ralegh (c) Sir Thomas Wyatt (d) Thomas Sackville 58. Prince Arthur, the hero in the Faerie Queene, is to marry...in the end. (a) Lady Diana (b) Hellen of Troy (c) Gloriana (d) Elizabeth 59. The Faerie Queene is an allegory. In this poem Elizabeth is allegorised through the character (a) Duessa (b) Archimago (c) Artegal (d) Gloriana 60. Spenser wrote an elegy entitled “Astrophel”. Whom did he commemorate in this elegy? (a) Chaucer (b) Sidney (c) John Donne (d) None of these