Exporter Behavior, Country Size and Stage of Development

advertisement

Exporter Behavior, Country Size and Stage of Development*

Ana M. Fernandes

Caroline Freund

Martha Denisse Pierola

and Tolga Cebeci

November 2013

Abstract

We present new data on exporter characteristics for 45 countries and study how they vary with

country size and stage of development. The evidence implies that larger and more developed

countries have more exporters, which are on average larger and more diversified, and an

increasing share of exports is controlled by the top 5 percent of exporters. The channel through

which the number of exporters expands matures as countries develop—exporter turnover plays a

significantly more important role in countries at an early stage of development, while higher

survival rates of new exporters promote creative destruction in more developed countries, with

net entry being invariant to income. Overall, the evidence points toward allocative efficiency in

export markets as countries grow. We discuss the findings considering recent trade theories with

heterogeneous firms.

JEL Classification codes: C81, F14.

Keywords: exporter dynamics, exporter growth, firm-level data.

*

Ana Fernandes, Martha Denisse Pierola, and Tolga Cebeci are at the World Bank; Caroline Freund is at the Peterson Institute

for International Economics and CEPR. We are grateful for the support of the governments of Norway, Sweden and the United

Kingdom through the Multi-Donor Trust Fund for Trade and Development. We also acknowledge the generous financial support

from the World Bank research support budget and the Knowledge for Change Program (KCP), a trust funded partnership in

support of research and data collection on poverty reduction and sustainable development housed in the office of the Chief

Economist of the World Bank (www.worldbank.org/kcp). We thank Mario Gutierrez-Rocha and Jamal Haidar for their

contribution to this project and Erhan Artuc, Richard Baldwin, Peter Klenow, Aaditya Mattoo, Sam Kortum, and Andres

Rodriguez-Clare for many useful comments and discussions. We thank Alberto Behar and Madina Kukenova for collaboration

with the project early on and Francis Aidoo, Paul Brenton, Maurizio Bussolo, Huot Chea, Julian Clarke, Alain D’Hoore, Pablo

Fajnzylber, Elisa Gamberoni, Sidiki Guindo, Javier Illescas, Mehar Khan, Sanjay Kathuria, Josaphat Kweka, Erjon Luci, Mariem

Malouche, Eric Manes, Yira Mascaro, Mamadou Ndione, Zeinab Partow, Stefano Paternostro, Jorge Rachid, Richard Record,

Jose Guilherme Reis, Jose Daniel Reyes, Nadeem Rizwan, Liviu Stirbat, Dimitri Stoelinga, Daria Taglioni, Maria Nicolas, Erik

von Uexkull, Cristian Ugarte, and Ravindra Yatawara for facilitating the access to the data for developing countries. We thank

Lina Ahlin, Martin Andersson, Juan de Lucio, Emmanuel Dhyne, Luc Dresse, Cédric Duprez, Richard Fabling, Jaan Masso, Raul

Minguez, Asier Minondo, Andreas Moxnes, Francisco Requena, Lynda Sanderson, Joana Silva, Priit Vahter, and Hylke

Vandenbussche for providing us with measures for developed countries. We thank workshop participants at the Empirical

Investigations in International Trade at Santa Cruz, the Graduate Institute in Geneva, the World Bank, the World Trade

Organization, and the International Trade Center for useful suggestions. The findings expressed in this paper are those of the

authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank.

I. Introduction

We present new evidence on how the characteristics and dynamics of a country’s exporters vary

with country size and stage of development. A number of studies use data from individual

countries or a small group of countries in a region to demonstrate how firms export.1 Some

commonalities arise: exports are found to be concentrated in a small share of large firms that

export many products to many markets and high rates of entry and exit into exporting are

typically found. However, because the studies involve single countries or groups of similar

countries, it is not possible to determine how exporter behavior evolves with country

characteristics. In addition, while many of the conclusions appear to be comparable across

countries, it would require a larger sample to generalize the existing results across countries that

differ in income and population. This paper fills this gap in the literature by presenting a large

cross-country database of exporter behavior and exploring how exporter characteristics and

dynamics vary with country size and stage of development, and also what features are common

to all economies.

Specifically, we gather exporter-level customs information from 38 developing and 7

developed countries around the world to build the “Exporter Dynamics Database” (henceforth

referred to as the Database), containing comparable measures of exporter, product and market

dynamics. The Database contains measures at different levels of aggregation: a) country-year, b)

country-year-product (HS 2-digit, HS 4-digit, or HS 6-digit) and c) country-year-destination

mostly for the period between 2003 and 2010 (with longer time series for some countries). The

Database covers different aspects of firm dynamics, firm-product and firm-destination dynamics,

1

See Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (2008) for France; Eaton et. al. (2008) for Colombia; Amador and Opromolla (2013) for

Portugal; Iacovone and Javorcik (2010) for Mexico; Andersson, Lööf, and Johansson (2008) for Sweden, Albornoz et. al (2010)

for Argentina; Freund and Pierola (2010) for Peru; Manova and Zhang (2012) for China, Masso and Vahter (2011) for Estonia,

De Lucio et. al. (2011) for Spain, Ekholm, Moxnes, and Ulltveit-Moe (2012) for Norway, Fabling and Sanderson (2012) for New

Zealand, Mayer and Ottaviano (2008) for several EU countries, among others. See also Bernard et. al. (2007, 2011a) for US and a

review of the empirical literature, respectively.

2

as well as exporter growth patterns, concentration, and diversification in the non-oil exporting

sector.

This paper introduces the Database and establishes several novel stylized facts on how

exporter characteristics and dynamics vary with country characteristics. The distinguishing

feature of these stylized facts is that they could not have been uncovered using any other crosscountry source of trade data available to date. We also confirm or generalize facts found in the

recent empirical trade literature.

First, we examine the relationships between exporter characteristics and both country size

and stage of development. Controlling for the sectoral distribution of exports, we find that larger

and more developed economies have a greater number of exporters, larger average exporter size,

more diversified exporters, and that total exports are more concentrated in the top 5 percent of

exporting firms. Similar results are found when we control for export destination. These results

imply that as countries grow and exports expand, the export expansion happens through both the

intensive and extensive margins, and more resources flow to the larger and more diversified

firms.

Second, we study how exporter dynamics change with stage of development and country

size.

We find that rates of both entry and exit into exporting are decreasing in stage of

development, after controlling for sector fixed effects or destination effects, yielding similar rates

of net entry across rich and poor countries. There is also evidence that survival rates of entrants

into export markets increase as countries develop. Exporter dynamics are, however, not robustly

correlated with country size. This implies that exporter dynamics mature as countries grow, first

fueled by trial and error and later by more resilient exporters.

3

We also confirm for a large number of developing countries the well-known fact from the

literature focusing on individual countries that total exports are largely dominated by multiproduct multi-destination exporters, but these account for a small share of the number of

exporters. In particular, exporters selling more than four products to more than four markets

account for 60 percent of exports on average. In line with our earlier results on concentration

and diversification, we find that within broad sectors, these multi-product multi-destination

exporters make up a larger share of exporters and account for a larger share of total exports as

countries develop—again suggesting that a larger share of resources are directed to the most

diversified (and productive) firms as countries grow.

Overall the results imply that larger and more developed economies have more

competitive export sectors, with a greater share of larger and more diversified firms, as well as

more efficient creative destruction. While the standard heterogeneous firm model of trade does

not offer definitive predictions about country size or stage of development and exporter

characteristics, we discuss some adaptations that are consistent with these facts. In particular,

allowing variation among countries in the shape of the firm productivity distribution, such as

Spearot (2013), or allowing a wider support for the firm productivity distribution in bigger and

richer countries, in a model with a truncated distribution, such as Helpman Melitz and

Rubenstein (2008), can help to explain why average size and concentration vary with stage of

development. Trade models which highlight the greater productivity of multi-product and multidestination firms, such as Bernard, Redding and Schott (2011b), are consistent with our findings

on firm level diversification and stage of development. Trade models incorporating uncertainty

about a firm’s profits in foreign markets offer predictions similar to our results on entry and exit.

More broadly, the evidence supports allocative efficiency as countries grow in the sense that

4

resources are increasingly controlled by larger and more diversified exporters and dynamics

involve lower gross flows for the same amount of net entry.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section II describes briefly the Database.

Section III presents three new stylized facts based on the Database. Section IV discusses models

that provide a theoretical framework to understand the facts presented. Finally, Section V

concludes.

II. The Exporter Dynamics Database

The Exporter Dynamics Database is constructed using customs data, covering the

universe of annual exporter transactions for 37 developing countries and 8 developed countries.2

The Database includes the basic characteristics of exporters in each country (e.g., number of

exporters, average exporter size and exporter growth rates), concentration/diversification (e.g.,

Herfindahl index, share of top exporters, number of products and destinations per exporter), firm,

product and market dynamics (e.g., entry, exit and one-year survival rates of entrants) and unit

prices (e.g., per exporter of a given product). The measures are available at different levels of

aggregation: a) country-year (98 measures), b) country-year-product (HS2, HS4, or HS6) (113

measures, 113 measures, and 89 measures, respectively) and c) country-year-destination (74

measures). The list of measures under each category and for each type of aggregation level is

presented in Appendix 1 along with the corresponding formula. The Database is publicly

available at http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/exporter-dynamics-database. Details on how

2

The group of countries is determined by the willingness to share data by local officials or other researchers who have access to

customs data. While the data underrepresent industrial countries and Asia, the patterns we find are robust and available statistics

from other studies, such as for the US and the EU, are consistent with the patterns observed here. We aim over time to expand

coverage of the Exporter Dynamics Database.

5

the countries’ customs data were cleaned and harmonized, and how the Database was

constructed are provided in Appendix 2.

Table 1 presents a summary of a representative set of measures in the Database, including

number of exporters, average and median exporter size, share of top 5 percent of exporting firms,

number of HS 6-digit products exported per firm, number of destinations served per firm, entry,

exit and entrant survival rates as well as total exports per country. We report averages per

country for the period 2006-2008, which is the period most commonly covered across countries

and captures trade performance before the global financial crisis that started at the end of 2008.3

Table 2 presents the same set of measures in the Database but for groups of HS 2-digit sectors,

where the measures for each sector group are obtained as averages across all countries that

export that particular group of HS 2-digit sectors, again focusing on the period 2006-2008.

Some interesting cross-country patterns emerge from Table 1. First, there is tremendous

variation across countries in the export base (number of exporters) and the average exports per

firm. Among developing countries, the largest numbers of exporters are found in Turkey and

Mexico followed by South Africa and Brazil (around 20,000) whereas the smallest pools of

exporters are found in Niger and Mali (around and below 300), followed by Burkina Faso, Laos,

Yemen, and Cambodia. This pattern seems to mirror the countries’ level of development, and

this link will be studied further in Section III. The number of exporters per capita is also largest

in the richer countries in the sample.

Average exports per firm are the highest for Belgium, followed by Brazil, Chile, and

Mexico (in the range of 7-8 million USD). Albania, Lebanon, Macedonia, Yemen, and Kenya

3

Note that the sharp drop in world trade ensuring from the global financial crisis occurs in 2009 not in 2008. For countries for

which data is available for only 1 or 2 years within the period 2006-2008 we compute the average based on those years. For

Kuwait and Portugal the data coverage does not include that period. Hence we use averages for the 2009-2010 period for Kuwait

and averages for the 2003-2005 period for Portugal in Table 1. However, these two countries are excluded from all summary

statistics and regressions shown from Table 4 to Table 7, though including them makes little difference.

6

exhibit the lowest average exports per firm (less than 800,000 USD). The tremendous difference

between mean and median exports per firm reflects the highly skewed exporter size distributions

in all countries with some very large exporters driving total exports.4 For Botswana, Chile, Mali,

Peru, South Africa, Mexico, and Malawi the skewness in the exporter size distribution is further

confirmed by the very high share of exports—more than 90 percent—accounted for by just the

top 5 percent of exporters. Interestingly, for most other developing countries those shares are

smaller than those for the developed countries in the sample, such as Norway, Sweden, and New

Zealand. Similarly, the U.S. and other European countries also exhibit high concentration, with

the top 5 percent of firms accounting for 80 percent or more of trade, as shown by Bernard,

Jensen, and Schott (2009) and Mayer and Ottaviano (2008) respectively.

The average number of products per exporter also exhibits a high degree of heterogeneity

across countries, ranging from 2 in Laos to 15 in South Africa. In terms of markets, the average

number of destinations per exporter is more similar across countries ranging from 1.4 in

Botswana to 4.8 in Cambodia and 6.8 in Belgium.

The measures of exporter dynamics also exhibit important variability across countries.

Entry rates range from 22 percent in Brazil to more than 50 percent in Malawi, Yemen, Laos and

Tanzania while exit rates range from 22 percent in Bangladesh to 61 percent in Malawi.5 Firstyear survival rates of new exporters vary between 23 percent in Cameroon and 61 percent in

Bangladesh. The magnitude of the survival rates in Table 1 suggests an extremely high attrition

rate of new entrants after just one year in export markets, particularly in Africa.

4

Using the same cross-country exporter-level dataset used for the construction of the Database, Freund and Pierola (2012) show

that exports are dominated by a small group of very large exporters (so-called ‘superstars’). These firms are remarkably larger

than the rest, they participate in many sectors and most importantly, they define sectoral exports and drive the export growth

observed in most countries.

5

These rates of entry into and exit from export markets are substantially larger than the rates of entry into and exit in production

reported by Bartelsman, Haltiwanger, and Scarpetta (2013). Focusing on census/registries of manufacturing firms (excluding 1employee businesses) they document turnover of 10-20 percent in industrial countries and somewhat higher in developing

countries.

7

The measures in Table 2 show a less pronounced variation in the number of exporters

across sectors. The number of exporters is higher for machinery (electrical and mechanical) and

plastics. Similar to the pattern within countries, the distribution of exporter size is also skewed

within sectors: the difference between average and median size is considerable. Larger exporter

size is more common in sectors that are highly resource-driven (mineral products and precious

metals) and where increasing returns to scale are important. As far as firm concentration is

concerned, the variation in shares of top exporters across sectors is not as wide as it is in the case

of countries. Again, precious metals and minerals are among the most concentrated sectors,

while firm concentration is lower in agricultural sectors. The average measures for product and

market diversification are more homogenous across sectors than across countries. Finally,

regarding exporter dynamics, entry and exit rates tend to be slightly higher in machinery and

transport, while exporter survival is slightly higher in agriculture.

In the analysis below, we also use data from the World Development Indicators (WDI) of

the World Bank on GDP and on GDP per capita in constant 2005 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

USD.6

III. Exporter Features and Country Characteristics

In this section, we evaluate how exporter characteristics and dynamics vary with country

size and stage of development. We first show the importance of both country and sector

characteristics in explaining exporter behavior. We then present three stylized facts on how the

structure of exporters changes as countries get larger or richer, controlling for sectoral variation

in exports and variation across destinations.

6

Note that all results presented from Table 4 to Table 7 are robust to the use of GDP and GDP per capita in current USD or in

constant USD.

8

We begin by evaluating the relative importance of country fixed effects and either HS2digit sector fixed effects or destination fixed effects in explaining exporter characteristics and

dynamics. Specifically, we perform an ANOVA with country and HS2-digit fixed effects, and

separately with country and destination fixed effects, on the main measures that we will explore

in detail below. 7

Panel A of Table 3 shows the results of the ANOVA with country and sector fixed

effects. On average, country and sector effects explain over 60 percent of the variation in

exporter characteristics, though somewhat less of the variation in exporter dynamics.8 With the

exception of exporter size, product diversification, and entrant survival, country effects explain a

greater share of the variation than sector effects. Still, the significance of sector effects implies

that it will also be important to control for them as we examine the relationships between country

characteristics and exporter characteristics.

We next repeat the ANOVA exercise using the country-destination level data available in

the database. The results are reported in Panel B of Table 3, and show that country and

destination fixed effects together explain somewhat less of the variation in the statistics than did

country and HS2 fixed effects. However, except for number of exporters and product

diversification, destination effects prevail over country effects. In that sense, it will be important

to control for destinations to ensure the results are not being driven by variation in trade barriers

or other destination-specific market access costs.

Next we present three stylized facts first focusing on basic characteristics of exporters,

then exporter diversification, and finally exporter dynamics.

7

Note that the sample used for concentration (fourth column) is relatively smaller because the share of exports accounted for by

the top 5 percent of exporting firms can be calculated only if a country-sector-year cell includes more than 20 exporters.

8

The percentages accounted for by country, sector, and residual effects in Panel A or country, destination, and residual effects in

Panel B do not add up to 100 percent due to the unbalanced nature of each of the cross-sectional datasets. Namely, in Panel A not

all sectors are exported by all countries while in Panel B not all destinations are served by all countries.

9

Stylized Fact 1: Larger and more developed economies have a larger export base (number of

exporters), larger average exporter size, and more concentrated export sectors among firms

(even after controlling for the sectoral distribution of exports and export destinations).

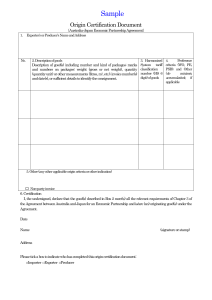

Figure 1 presents a scatter plot of export base, average exporter size, and concentration

and income per capita, using data averaged for the period 2006-2008.9 The figure shows that

more developed economies have a larger number of exporters, larger average size of exporters,

and more concentrated export sectors in terms of firms. Figure 2 uses income instead of income

per capita and shows that larger countries have more exporters, larger exporters, and higher

concentration. We next explore these relationships in more detail, controlling for sectoral

variation in exports, considering cross-section regressions based on the data averaged across the

period 2006-2008.

Table 4 reports the results from the cross-section regressions. Specifically, we regress

total exports, export base, exporter size, and firm concentration on GDP per capita and GDP.

Columns (1)-(4) report the results using the country data. All measures are positively associated

with country size and stage of development, though the correlation with average exporter size

appears to stem from country size and not from stage of development. Similarly, country size has

a greater impact on the number of exporters than the level of development. However, in terms of

firm concentration, stage of development seems to matter more.

A concern about the regressions in columns (1)-(4) is that larger or more developed

countries may be more likely to specialize in sectors with increasing returns to scale, thus the

results may be driven by the sectoral composition of trade and not by a change in exporter

9

The other scatter plots on diversification and exporter dynamics in Figures 1 and 2 are discussed as part of the stylized facts

below.

10

characteristics within sectors as countries develop. To account for this possibility, we next

consider the same measures at the country and HS 2-digit sector level averaged across the period

2006-2008 and control for HS 2-digit sectoral fixed effects.10 The results, shown in columns (5)(8) of Table 4, indicate that controlling for potential differences across sectors, larger and richer

countries have both more and larger exporters. In addition, within sectors, the correlations with

export concentration become highly significant for both stage of development and country size,

suggesting that within sectors exports are more concentrated among the top firms in both richer

and larger countries. The economic magnitude of these effects is such that if GDP per capita

increased from the value for the country in the 25th percentile (Laos) to the value for the country

in the 75th percentile (Mauritius) the number of exporters would increase by 92 percent, average

exports per firm would increase by 63 percent, and the share of the top 5% exporters would

increase by 8 percentage points.11

Columns (9)-(13) in Table 4 use the country-destination level data and results are

qualitatively similar. Bigger and richer countries have more exporters, larger exporters, and

greater export concentration in any given destination. These regressions show that even after

controlling for market-specific characteristics, such as trade costs, more developed and larger

countries have larger exporters that export larger volumes.

Note that when we control for either sector or destination, the results on average size and

concentration are both statistically and economically more significant than on aggregate. This

implies that within a destination or sector, exporters from smaller and poorer countries on

10

For these, and all subsequent regressions at the country-sector level, robust standard errors clustered at the country level are

reported.

11

These magnitudes are obtained as the product of the difference in logs GDP per capita, 1.744, and the corresponding

coefficient in columns (6)-(8) of Table 4: 0.527, 0.359, and 0.045.

11

average export relatively less; but that across all sectors or all destinations, they export relatively

more in sectors with large exporters or to high-demand destinations.

Stylized Fact 2:

Controlling for the sectoral distribution of exports, larger and richer

countries have more diverse exporters in terms of products and/or markets. Stage of

development matters more for exporter diversification than does country size.

Richer

countries also have a larger share of multi-product multi-destination firms and these firms

weigh more heavily in total exports.

We next examine the relationship between the average number of products and average

number of destinations per exporter and country characteristics. Figures 1 and 2 show that as

countries get richer and larger, exporters tend to be more diversified product- and destinationwise. In Table 5 we look at these relationships in more detail.

Columns (1) and (2) in Table 5 report the results from the cross-section regressions of the

average number of products and destinations per firm on GDP per capita and GDP using the

2006-2008 averaged country data. We find that firms in richer countries are more diversified

with respect to products and firms in larger countries serve a greater number of destinations. As

shown in the ANOVA (Table 3), sector effects explain a large share of the variation in the

average number of products per exporter. While this could suggest that multi-product firms are

relatively more common in some sectors, it could also reflect that the differences in product

diversification are endogenously determined by the structure of the HS classification, which

entails very different degrees of disaggregation by 2-digit sectors.

Next, we control for HS 2-digit fixed effects. The results, shown in columns (3) and (4),

provide strong evidence that within sectors exporters in richer countries export more products

12

and export to more destinations. However, the coefficients on per capita income are much larger

than those on income (and in the case of product diversification only the coefficient on per capita

income is significant), indicating that exporter diversification is associated to a greater extent

with stage of development than with country size. In terms of economic significance our results

imply that increasing GDP per capita from the 25th to the 75th percentile in our sample would

increase the number of products per exporter by 16 percent and the number of destinations per

exporter by 21 percent. In column (5), we examine how exporter diversification across products,

within a destination, changes as countries grow. Again, we find a strong positive correlation

with per capita income.

Another way of looking at the importance of diversification is to examine the share of

multi-product multi-destination firms in total trade. The recent trade literature shows a dominant

role for firms that export many products to many destinations in explaining trade flows (see, for

example, Bernard, Jensen and Schott 2009 on the U.S.; Eaton, Kortum and Kramarz, 2008 on

France; and Amador and Opromolla, 2013 on Portugal). Using the firm-level information from

developing countries over the 2006-2008 period, we calculate for each country the average share

of exporters and of total exports accounted for by single-product single-destination firms and by

firms exporting to more than four countries and to more than four destinations and record them

in Table 6.12 Unfortunately, we do not have access to the firm-level raw data for the developed

countries, used in other parts of this paper, to calculate these indices for them. The results show

that single-product, single-destination firms represent more than a third of exporters on average

across developing countries. They represent an even higher share over 40 percent in most

12

This analysis is based on an additional component of the Database which is a set of matrix tables showing for each developing

country and year the joint distribution of exporters and of total exports by the number of HS 6-digit products exported and the

number of destination markets served. This information can provide insights onto the importance of multi-product multidestination exporters across countries and over time.

13

African countries as well as in Albania and Mexico. The percentages shown in Table 6 are quite

close to the 40 percent reported by Bernard, Jensen and Schott (2009) for the U.S.13 However,

these single-product single-destination firms account for a minimal fraction of total exports, on

average less than 3 percent across countries. That fraction is particularly low in Botswana, Costa

Rica, and Niger at 0.5 percent or less.

Table 6 also shows that firms exporting more than four products to more than four

destinations represent a relatively small proportion of exporters, 12 percent on average across

countries. But those percentages exhibit a substantial degree of heterogeneity across countries

ranging from about 3.5 percent in Albania and Botswana to 29.4 percent in Cambodia. These

multi-product multi-destination firms account for a large share of total exports in all countries,

more than 60 percent on average. But again large differences are observed across countries: in

Cambodia, Costa Rica, and South Africa that share is actually close to 80 percent whereas in

Albania and Niger it is less than 30 percent.

We next examine how the share of multi-product and multi-destination firms varies with

stage of development and country size. As noted above, we do not have access to this data for

the more developed countries in our sample, giving us less variation in level of development. As

a result, we focus on country-sector data. Results are reported in columns (6) and (7) in Table 5.

Again we find that as countries develop, more resources are allocated to the more diversified

exporters within sectors.

Stylized Fact 3: Exporter turnover is significantly lower in more developed countries, while net

entry is invariant with respect to income per capita.

13

Note, however, that the U.S. percentage is based on products defined at the HS 10-digit level.

14

Figures 1 and 2 show exporter turnover and stage of development and turnover and

country size, respectively. In both cases, there is a negative relationship indicating that richer

and larger countries have lower entry and exit rates. We next explore these relationships in more

detail.

Columns (1)-(5) in Table 7 show the results from cross-section regressions of exporter

entry, exit, survival of new exporters, net entry, and turnover on income and income per capita

based on the 2006-2008 averaged data. The estimates show that entry and turnover rates are

lower in larger countries, but point to no relationship between net entry or entrant survival rates

and stage of development.

In columns (6)-(10) in Table 7 we report results using country-sector level data,

controlling for sector fixed effects. This is crucial here as some sectors have much lower

turnover than others, as highlighted by the relative importance of sector effects in the ANOVA

(Table 3). The results show that controlling for the sectoral composition of trade, stage of

development has important effects on exporter dynamics. In particular, richer countries have

lower turnover and higher rates of survival of new exporters, leaving net entry roughly

unchanged. The economic magnitudes of the results are sizable—increasing GDP per capita

from the 25th to the 75th percentile in the sample would lead to a decrease in entry rates by 11.5

percentage points, would lead to a decline in exit rates by 12.4 percentage points, and to an

increase in the one-year survival rate of new exporters by 7.3 percentage points.

In columns (11)-(15) in Table 7 we report results using country-destination level data and

controlling for destination fixed effects. The results are qualitatively similar to the results using

country-HS2 data, though the magnitudes are smaller. In this case, there is also some evidence

that size matters, with larger countries having lower entry and exit and higher survival rates.

15

The coefficients on entry, exit, survival, and turnover are both economically and

statistically more significant when either sectors or destinations are controlled for than when

aggregate data are used, implying that poorer countries tend to have exporters that enter and exit

less in industries and destinations where entry and exit is rare. These results show that exporter

dynamics change as countries get richer. In poor countries turnover is largely a process of trial

and error where many firms enter into export markets and exit almost immediately. In rich

countries, fewer but more resilient exporters enter in any given year.

Robustness of Stylized Facts

In Appendix 3, we consider a number of alternative specifications to test the robustness

of these results. (i) We re-estimate the regressions using country-destination data but focusing

only on manufacturing industries (available only for the 32 developing countries for which we

have access to the raw exporter-level data). (ii) We include distance in the cross-section

regressions that use country-destination data to control for trade costs. (iii) We re-estimate the

specifications for average exporter size, using data on incumbent exporters only, in order to

exclude possible biases due to “partial year” data. 14 Finally, (iv) for the results on average

exporter size and number of exporters, we re-estimate the regressions using a short panel from

2004 to 2008 with country-sector and country-destination fixed effects to see how exports adjust

over time as income grows. 15 For this specification, we include GDP and GDP per capita

14

Bernard et al. (2013) show that the entry and exit of firms into and from export markets at different points in a calendar year

means that the use of calendar annual data on export values to measure the average size of exporter entrants or exiters may

introduce a bias - mainly their size being under-estimated during the first year - which they refer to as “partial year” effects. Our

consideration of the average size of incumbent exporters addresses this concern to the extent that bias should not permeate the

calculation of average size for exporters that have not interrupted their exporting activity.

15

We also try panel regressions with the other dependent variables: concentration, diversification, and dynamics. All results are

robust in sign and significance when country-sector or country-destination fixed effects are included, however when we include

year fixed effects, many of the results become insignificant—though the signs remain robust. This suggests that the change over

the period in these variables is coming largely from global demand growth, making it difficult to identify correlation with home

16

separately, as over a short period they are highly correlated because population is relatively

constant. We consider exports to the top 10 destinations only so as to avoid noise due to small

destinations or changes in destinations. This final specification shows that in the short run as

countries grow, much of the corresponding export growth is driven by larger exporter size as

opposed to more exporters, especially when per capita income is considered. The other results

remain qualitatively similar for all alternative specifications.

IV. Theoretical Interpretation

In this section, we review the evidence presented above on exporter characteristics and

stage of development in light of recent trade models with heterogeneous firms.

The basic theory of trade and heterogeneous firms, following Melitz (2003), focuses on

the reallocation of production across firms within an industry in response to trade liberalization.

More recently, efforts have been made to extend the model to make it consistent with other

observed features of exporter behavior that have become known via the growing empirical work,

such as, the numerous zeros in international trade (Helpman, Melitz and Rubinstein 2008 and

Eaton, Kortum and Sotelo 2012), or the large numbers of very small exporters (Arkolakis 2010).

While the theory was not developed to explain how economies at various stages of development

or scales differ in terms of exporter behavior, there are some features of these models we can use

to address these relationships.

The standard heterogeneous firm model assumes firms are differentiated by the variety

they produce and by their productivity, and that there is a fixed entry cost into exporting. A firm

will enter the export market if its net export profits cover the fixed exporting cost. Because of

country characteristics. Note that this is a fairly strong test of the results, as the time period is only 5 years and the fixed effects

swamp up much of the variation (see the high R squares in Table iv in Appendix 3).

17

the entry costs, there is a cutoff productivity level, such that firms at or above it will export while

those below it produce only for the domestic market.

Thus, firms that export are more

productive than firms that produce only for the domestic market, and export quantity is

increasing in productivity. This is consistent with our findings to the extent that developed

countries are richer because their firms are more highly productive or they have a greater number

of highly productive firms. Thus, if we allow for variation in the productivity distribution of

firms across countries, the model would be consistent with our findings on stage of development

although it would not help to explain them. However, it would be harder to justify our findings

on country size.

This is in part because constant elasticity of substitution (CES) preferences assumed in

the standard model imply that the cutoff productivity level for an exporter to enter a market does

not change with domestic market size, which implies that differences in the number or size of

exporters must stem from trade costs. Moreover, in these models, if variation stems from fixed

trade costs, exporter size and the number of exporters in a country would be inversely related

since a higher productivity threshold would mean that there are fewer but bigger exporters.

While if variation stems from variable trade costs, then all of the adjustment should be in the

extensive margin. Thus, our findings of a positive correlation of country size and stage of

development with number of exporters and exporter size could not be generated.

The higher concentration of exports in the top 5 percent of exporting firms in larger

countries and at higher levels of income that we show is also not consistent with a standard

heterogeneous firm model. With firm productivity following a Pareto distribution, the larger

average exporter size and the increasing concentration at the top of the size distribution as

countries grow could come from either more skewed distribution in the Pareto shape parameter

18

(a lower shape parameter) or a larger support for the firm productivity distribution in bigger and

richer countries.

A number of models are consistent with larger markets having more and larger firms, but

not necessarily with exporters from larger markets exporting larger volumes to any given

destination. For example, Melitz and Ottaviano’s (2008) model with variable markups allows

aggregate demand to matter for entry and firm size. In their model, larger markets demand more

of each variety, generating more entry. However, when prices rise, demand falls off more

sharply for each specific variety, inducing high-cost firms to exit. As a result, larger markets are

characterized by tougher competition, with both more firms and bigger firms.16 This model can

explain why firms export larger quantities to larger destination markets, but not why firms from

larger markets export more than firms from smaller markets to a particular destination market.

In recent work, Spearot (2013) adapts the Melitz-Ottaviano model to address this issue by

allowing the Pareto shape parameter of the firm productivity distribution to vary across

countries. He shows that such an accommodation can explain variation in the average size of

exporters. He further shows that the response of export flows across countries of varying sizes to

a trade shock can be used to estimate the shape parameters across countries. Using this

methodology, he finds that larger and richer countries have more skewed distributions, a result

that could explain our findings on the increasing share of the top 5 percent and large average size

in large and rich countries. His model, however, does not explain why the shape parameter is

more skewed in larger or richer countries.17

16

Chaney and Ossa (2012) also address the relationship between market size and firm size. They develop a model with labor

division, where the production of a final good requires the performance of a number of tasks, each of them carried out by a

specialized team. The larger the output, the larger the number of teams and the lower the average costs–each team performs more

efficiently lowering marginal costs. In this context, an increase in market size –represented by an increase in the number of

consumers–increases demand elasticity and is associated with more firms and larger firms.

17

One potential explanation for why this might be the case in richer countries derives from the work of Hsieh and Klenow

(2012), who find that weak firm dynamics prevent developing countries from reaping the benefits of large firms. They

19

Alternatively, Helpman, Melitz and Rubinstein (2008) employ a heterogeneous firm

model with a productivity distribution truncated from above to explain why some countries have

zero trade. Such a model may also be able to explain why average exports are greater in larger

and richer countries if the upper limit is increasing in size and stage of development. For

example, a larger pool of potential technologies or managers in bigger and richer countries may

yield a wider support. In this case, large and rich countries would have some very large

exporters, raising the average size and the share of exports in the top 5 percent. Overall, the

results on size and concentration are consistent with variation in the firm productivity

distribution across countries, and more specifically with either a lower shape parameter or a

wider support in bigger and richer countries. This is an important area for future research.

Turning next to our results on diversification, a number of trade models with

heterogeneous firms have also incorporated multi-product multi-destination firms. For example,

in the model of Bernard, Redding and Schott (2011), firms are heterogeneous in terms of overall

ability and expertise in each product, in addition they face fixed costs in terms of labor to export

each product and serve each market. Only higher ability firms are able to generate variable

profits to cover those fixed costs and thus supply a wider range of products to each market. This

model helps to explain why the largest firms are multiproduct, as these are the most able firms,

and also why they account for such a high share of exports. It also allows for across and within

firm reallocation of resources in response to trade liberalization.

While, like the standard

heterogeneous firm model, the model does not directly address stage of development, assuming

richer countries have more able firms or managers, our results on increased diversification and

their increased share of exports as countries grow would hold. This helps to explain why richer

hypothesize that this could be the result of constraints to growth in developing countries, via for example taxes or weak

investment incentives, which constrain aggregate TFP because of a misallocation of resources away from the high-productivity

firms. Over time this would lead to too many small firms and not enough large firms.

20

countries have more diversified firms, and can also explain why these firms account for a larger

share of total exports as countries develop since there are more highly productive firms that are

able to export widely.18

What is harder to explain with existing trade models with heterogeneous firms are our

results on exporter turnover because those models have little to say about dynamics (Melitz and

Redding 2012). Some recent work, however, has used uncertainty about export productivity to

explain the high rates of entry into and immediate exit from foreign markets observed in the data

(Albornoz et. al. 2010, Segura-Cayuela and Vilarrubio 2008 and Freund and Pierola 2008). In

these models, there is high entry because there is effectively an option value of remaining in the

export sector if the firm is successful in foreign markets.

To illustrate how this works, consider the following simple case: each firm has

probability p of getting high positive export profits, H, and probability (1-p) of getting negative

export profits, L. Exporting requires fixed cost F. In a repeated game, with discount factor δ

(smaller than 1), a firm will enter the export sector if

(1)

(

)

The important point is that there is an asymmetry because getting a good profit draw yields

positive profits forever in this repeated game (

), while export failure yields only one period of

negative profits (L) followed by exit. This implies that a firm may enter the export sector even if

its expected one-period profits are negative, pH+(1-p)L<0. This can explain why there is so

much entry into exporting with high rates of immediate exit corresponding also to low one-year

survival rates of new exporters.

18

Note that the firm-level results are distinct from evidence on production and industrial exports on diversification, where

empirical evidence shows that countries first diversify and only later specialize (Imbs and Wacziarg 2003 , Klinger and

Lederman 2006). The results are not contradictory, as it is possible that firms on average become more diversified as countries

grow, but if the products are ultimately similar across firms at high levels of income, this is consistent with increased

specialization by industry or product at the country level.

21

For both exporter entry and exit to be negatively correlated with the level of

development, while net entry is roughly invariant, it would be necessary in the model above that

fixed costs of exporting are lower, the discount factor is higher, or that the gap between H and L

is greater in developing countries.19 The first, lower fixed costs of exporting, seems unlikely

given that existing evidence points to higher costs of entering export markets in poorer

countries.20 The second, higher discount factor also seems unlikely as developing countries have

higher interest rates/discount rates for the future, indicating that money now is worth more than

money later in poor countries.

Finally, firms in developing countries may have greater

variability in profit draws (outcomes). Even if one-period expected profits are the same across

countries (pH + (1-p) L= k), a greater H and lower L will lead to more entry because H weighs

more heavily on the decision to enter. In this case, the first term in Eq. (1) would be relatively

larger for developing countries, implying that more firms would enter the export sector in poorer

countries, while a similar or even a lower fraction of entrants would survive (depending on p),

yielding higher overall entry and exit. Exit goes up precisely because there are more entrants.

Indeed, this is consistent with high correlations between entry and exit at the country level and

country-sector level. For example, using the 2004-2008 panel data, the simple within-country

correlation between entry and exit is 0.77 and the within country-sector the correlation is 0.76.

Search and matching models of trade partnerships can also generate similar exporter

dynamics. While these models were designed to understand the importance of networks in

international trade, they also offer conditions under which there will be more or less search. For

example, Rauch and Watson (2003) show that with imperfect information about the ability of a

19

Note that a higher probability of a good outcome in developing countries would create more entry but is not consistent with the

lower rates of survival that are observed in developing countries.

20

A simple correlation between various indicators on trade costs from the Doing Business database and GDP per capita using all

available countries as well as the countries in the Exporter Dynamics Database sample is clearly negative and significant.

22

developing country exporter to supply a large order, developed country buyers may have more

small trials before investing in a developing country exporter for a long-term trade relationship.

This would lead to more exporter entry and exit from developing countries. In a different type of

model, Araujo, Mion, and Ornelas (2012) integrate work on institutions and heterogeneous firm

models of trade and show that there is less entry, less exit, less turnover and greater survival rates

in countries with better institutions, resembling closely our findings with per capita income.

In sum, the results on exporter characteristics are consistent with various strands of the

recent theoretical work, with some accommodations. The results on average exporter size and

increasing concentration are consistent with a heterogeneous firm trade model with variation

across countries in the Pareto shape parameter or the support of the firm productivity

distribution. The results on diversification and stage of development follow from theories with

multi-product and multi-destination firms.

The results on exporter dynamics and stage of

development are consistent with models with uncertainty about export profitability or the

viability of a particular importer-exporter match.

Overall, the systematic variation in exporter behavior across countries by size and stage

of development observed in the data is suggestive of more efficient resource allocation as

countries get richer and larger. While tweaking existing models can explain specific features of

the data, the results point to the need for a dynamic model to develop a better understanding of

how exporter behavior changes with country size and stage of development. For example, why

would the Pareto shape parameter be more skewed or the support wider in more developed or

larger countries? Such a model may also help explain whether the changing firm characteristics

and dynamics help drive income growth or whether demand growth drives firm behavior.

23

V. Conclusion

While the literature on exporter dynamics is rapidly growing, there has not been a

comparison across a large number of countries of different sizes and at differing stages of

development. The Exporter Dynamics Database presented in this paper addresses that limitation

by providing the research community and policymakers with a set of measures of exporter

characteristics and dynamics that allow for cross-country comparisons, that expand our

understanding of how exporting happens and show novel results on how these are related to

stage of development. The Database compiles measures for 45 countries (37 of which are

developing countries) covering the universe of firm-level export transactions primarily for the

period between 2003 and 2010.

The data point to systematic ways in which the micro structure of exports changes as

countries develop. As countries grow, they have more and larger (likely better) exporters and

also relatively more concentrated export sectors. Product and market diversification of exporters

is also positively correlated with stage of development. Together with results from previous

studies showing that exporters are more productive than non-exporters and larger exporters are

more productive than smaller exporters, our results point towards allocative efficiency in export

markets as countries develop.

Of interest is how reallocation happens. In particular, exporter dynamics are also closely

linked with stage of development, with richer countries experiencing lower entry and exit rates,

higher survival of new firms, and net entry invariant to per capita income. This implies that as

countries develop, there is less entry of firms that immediately exit to generate the same rates of

net entry. We highlight that with uncertainty about export profitability at the firm level, this

could reflect lower variability in export potential at higher stages of development.

24

The measures in the Database will allow the examination of several interesting crosscountry questions, cross-country cross-sector questions, and within-country questions. The

measures can also be used as controls in estimations that require exporter characteristics at the

country-industry level. In particular, as the measures in the Database offer the first opportunity to

study exporter characteristics and dynamics on a global basis, some of the facts described above

open the door to questions such as: Does trade promote growth via firm size or firm count? How

can countries attract more large multi-product firms? What determines exporter survival? How

comparative advantage is related to the typical exporter characteristics in an industry? And many

others that will hopefully be addressed in future research to be conducted using the Database.

25

References

Amador, J. and L. Opromolla (2013). “Product and Destination Mix in Export Markets,” Review

of World Economics 149: 23-53.

Albornoz, F., H. Calvo Pardo, G. Corcos and E. Ornelas (2010) “Sequential Exporting,” Journal

of International Economics 88: 17-31.

Andersson, M., H. Lööf and S. Johansson (2008). “Productivity and International Trade: Firm

Level Evidence from a Small Open Economy,” Review of World Economics 144: 774-801.

Araujo, L., G. Mion and E. Ornelas (2012). "Institutions and Export Dynamics," CEPR

Discussion Papers 8809, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

Arkolakis, C. (2010). “Market Penetration Costs and the New Consumers Margin in

International Trade,” Journal of Political Economy 118(6): 1151–99.

Bartelsman, E., J. Haltiwanger and S. Scarpetta (2013). "Cross-Country Differences in

Productivity: The Role of Allocation and Selection," American Economic Review, American

Economic Association, vol. 103(1), pages 305-34, February.

Bernard, A., J. Jensen, and P. Schott (2009). “Importers, Exporters and Multinationals: A Portrait

of Firms in the U.S. that Trade Goods,” in T. Dunne, J. Jensen and M. Roberts (eds.), Producer

Dynamics: New Evidence from Micro Data. University of Chicago Press.

Bernard, A., J. Jensen, S. Redding, and P. Schott (2007). “Firms in International Trade,” Journal

of Economic Perspectives 21: 105-130.

Bernard, A., J. Jensen, S. Redding, and P. Schott (2011a). “The Empirics of Firm Heterogeneity

and International Trade,” NBER Working paper No. 17627.

Bernard, A., S. Redding, and P. Schott (2011b). “Multi-Product Firms and Trade Liberalization,”

Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1271-1318.

Bernard, A., R. Massari, J. Reyes, and D. Taglioni (2013). “Exporter Dynamics, Firm Size and

Growth, and Partial Year Effects,” World Bank mimeo.

Cebeci, T. (2012). “A Concordance Among Harmonized System 1996, 2002 and 2007

Classifications,” World Bank mimeo available at http://econ.worldbank.org/exporter-dynamicsdatabase.

Cebeci, T., A. Fernandes, C. Freund, and M. Pierola (2012). “Exporter Dynamics Database,”

Policy Research Working Paper No. 6229, The World Bank.

Chaney, T. and R. Ossa (2012). "Market Size, Division of Labor, and Firm Productivity," CEPR

Discussion Papers 9069, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

26

De Lucio, J., R. Mínguez-Fuentes, A. Minondo, and F. Requena-Silvente (2011). “The Extensive

and Intensive Margins of Spanish Trade,” International Review of Applied Economics 25: 615631.

Eaton, J., M. Eslava, M. Kugler, and J. Tybout (2008). “Export Dynamics in Colombia:

Transactions Level Evidence,” Borradores de Economia No. 522, Banco de la Republica,

Colombia.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, and F. Kramarz. (2008). “An Anatomy of International Trade: Evidence

from French Firms,” Econometrica 79: 1453-1498.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, and F. Sotelo. (2012). “International Trade: Linking Micro and Macro,”

NBER Working Paper 17864.

Ekholm, K., A. Moxnes, and K. Ulltveit-Moe (2012). “Manufacturing Restructuring and the

Role of Real Exchange Rate Shocks: A Firm-Level Analysis,” Journal of International

Economics 86: 101-117.

Fabling, R. and L. Sanderson (2012). “Whatever Next? Export Market Choices of New Zealand

Firms,” Papers in Regional Science 91: 137-159.

Freund, C. and M. Pierola (2010). “Export Entrepreneurs Evidence from Peru,” Policy Research

Working Paper No. 5407, The World Bank.

Freund, C. and M. Pierola (2012). “Export Superstars,” Policy Research Working Paper No.

6222, The World Bank.

Helpman, E, M. Melitz, and Y. Rubinstein (2008). “Estimating Trade Flows: Trading Partners

and Trading Volumes,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123: 441-487.

Hsieh, C. and P. Klenow (2012). “The Life-cycle of Plants in India and Mexico,” NBER

Working Paper 18133, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Iacovone, L. and B. Javorcik (2010). “Multi-Product Exporters: Product Churning, Uncertainty,

and Export Discoveries,” Economic Journal 120: 481-499.

Imbs, J. and R. Wacziarg (2003). "Stages of Diversification," American Economic Review,

American Economic Association, vol. 93(1), pages 63-86, March.

Klinger, B. and D. Lederman (2006). "Diversification, innovation, and imitation inside the

Global Technological Frontier," Policy Research Working Paper Series 3872, The World Bank.

Manova, K. and Z. Zhang (2012). “Export Prices across Firms and Destinations,” Quarterly

Journal of Economics 127: 379-436.

27

Masso, J. and P. Vahter (2011). “Exporting and Productivity: the Effects of Multi-Market and

Multi-Product Export Entry,” University of Tartu, Faculty of Economics and Business

Administration Working Paper No. 83.

Mayer, T. and G. Ottaviano (2008). “The Happy Few: The Internationalisation of European

Firms,” Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy 43: 135-148.

Melitz, M. (2003). “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry

Productivity,” Econometrica 71: 1695-1725.

Melitz, M. and S. Redding (2012). “Heterogeneous Firms and Trade,” NBER Working Paper

18652.

Segura-Cayuela, R. and J. Vilarrubia (2008) “Uncertainty and Entry into Export Markets,”

Banco de España Working Paper No. 0811.

Rauch, J. and J. Watson (2003). "Starting Small in an Unfamiliar Environment," International

Journal of Industrial Organization, Elsevier, vol. 21(7), pages 1021-1042, September.

Schott, P. and J. Pierce (2011). “Concording U.S. Harmonized System Categories over Time,”

Journal of Official Measures forthcoming.

Spearot, A. (2013). “Tariffs, Competition, and the Long of Firm Heterogeneity Models,”.

University of California – Santa Cruz. Mimeo

Wagner, R. and A. Zahler (2011). “New Exports from Emerging Markets: Do Followers Benefit

from Pioneers?,” MPRA Paper No. 30312, University Library of Munich, Germany.

United Nations (1998). International Merchandise Trade Statistics: Concepts and Definitions.

United Nations (2008). International Merchandise Trade Statistics: Supplement to the Compilers

Manual.

28

Figure 1: Correlations of Selected Database Measures with GDP per Capita

(averages over 2006-2008)

Number of Exporters - GDPpc

17

12

Mean Exports per Exporter - GDPpc

ESP

16

Ln Mean Exports per Exporter

BRA

15

NER

MWI

13

4

7

8

9

10

CRI

ZAF BWA

TUR

BGD

COL

CMR

ECU

JOR

EGYSLVDOM

GTM

UGA

LAO

BFA

TZA SEN PAK

MUS

NIC

IRN

BGR

KEN

YEM

MKD

LBN

ALB

11

6

7

8

Ln GDPpc

9

ESP

NOR

EST NZL

10

11

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.58

R-squared=0.13

Number of Products per Exporter - GDPpc

3

1

Share of Top 5% Exporters - GDPpc

CHL

PERZAF MEX

MUS

DOM

MKD

JOR

BGR

CMR

BRA

CRI

SLV COL

KEN

TUR

EGY ECU

LBN

GTM

UGA

NIC

MAR

PAK

IRN

SEN

BGD

SWE

NOR

ZAF

ESP

BEL

TUR

MUS

KHM

KEN

EST

GTM

MAR

NIC

SEN

SLVPER

PAK

1.5

ALB

YEM

CMR

MWI

BGD

TZA

NER MLI

BFA

UGA

LBN

MEX

BWA

BGR

IRN

CRI

BEL

EST NZL

SWE

NOR

COL

DOM

ECUMKD

ESP

CHL

ALB

JOR

1

.8

.6

YEM

NZL

2.5

LAO

TZA

BFA

2

MLI

Ln Number of Products per Exporter

BWA

MWI

NER

Share of Top 5% Exporters

SWE

PER

MAR

MLI

NER

6

CHL

MEX

KHM

14

10

6

8

Ln Number of Exporters

BEL

TUR

MEX

SWE

BEL

ZAF

BRA

NOR

PAK

BGR

IRN

NZL

COL

EGY

CHL

PER

BGD

MAR

LBN

KEN

EST

GTM

ECUMKD

CRI

SLVDOM

MUS

TZA

JOR ALB

BWA

NIC

UGA

CMR

SEN

MWI

KHM

YEM

LAO

BFA

MLI

.4

KHM

LAO

6

7

8

9

10

11

6

7

8

Ln GDPpc

9

10

11

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.08

R-squared=0.20

Entry Rate - GDPpc

2

Number of Destinations per Exporter - GDPpc

MWI

YEM

LAO

TZA

.5

BEL

CMR

UGA

IRN

.5

NOR

DOM

ALB

ESP

ALB

PER

BGR CHL

JOR

MKD

NIC

KHM

BGD

LAO

NER

EST

BWA

ECU

SEN

KEN

NOR

MEX

MAR

TUR

GTM SLV COL

MUS

CRI

ZAF

.3

1

SEN PAK

.4

TUR

ZAF

CHL

CRI

JOR

LBN

NZL

CMR

COL

EGY PER MUS

EST

KEN

MAR

GTM SLV

BGR

TZA

UGA

YEM

BFA

ECU

DOM

MKD MEX

MLI

NIC

IRN

BGD

MWI

MLIBFA

SWE

ESP

Entry Rate

1.5

KHM

PAK

BWA

BEL

NZL SWE

EGY

0

.2

BRA

6

7

8

9

10

11

6

7

8

Ln GDPpc

.6

BGD

KHMPAK

BRA TUR

Survival Rate of Entrants

YEM

.3

.4

BFA

MLI

UGA

DOM

LAO

BWA

BGR

.5

ESP

SEN

NOR

NZL BEL

SWE

NZL

BEL

CHL

KEN

TZA

EST

UGA

ESP

MWI

CMR

BRA

.2

BGD

7

BFA

EST

ECU

MEX

PER

CHL

MKD

NICMAR

ALB

JOR

COL MUS

KHM

SLV

GTM

TUR

EGY

PAK

CRI

ZAF

SEN

ZAF

CRI

ALB

MKD

SLVPER

MAR

MUS

GTM

COL

ECU IRN

DOM

BWA

MEX

NIC

MLI

.4

CMR

TZA

KEN

EGY

JOR

LAO

.3

.5

IRN

.2

Exit Rate

11

Survival Rate of Entrants - GDPpc

Exit Rate - GDPpc

6

10

R-squared=0.18

MWI

.6

9

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.14

8

9

10

6

11

7

8

9

Ln GDPpc

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.00

R-squared=0.12

29

10

11

Turnover Rate - GDPpc

1.2

Net Entry Rate - GDPpc

.1

LAO

MWI

UGA

YEM

1

JOR

ALB

ECU

CHL

PER

MKD TUR

KHM

SEN

EST

CRI

BEL

GTM

ZAF BWA

NIC

CMR

SLV

PAK

ESPSWE NOR

COL

DOM

NZL

MAR

BRA

MUS

EGY

MEX

BGR

YEM

KEN

IRN

TZA

CMR

LAO

DOM

BFA

UGA

KEN

MLI

.8

Turnover Rate

BWA

ECU BGR

PER

CHL

MKD

ALB

MEX

JOR

NIC

MAR

COL

MUS

TUR

GTM SLV

SEN

IRN

KHM

.6

.05

0

TZA

MLI

BFA

-.05

Net Entry Rate

BGD

PAK

BGD

EST

ESP

BEL

NZL SWE

CRI

ZAF

EGY

NOR

BRA

.4

-.1

MWI

6

7

8

9

10

11

6

Ln GDPpc

7

8

9

10

11

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.01

R-squared=0.16

Notes: The measures plotted are based on measures in the country-year level dataset averaged across the 2006-2008 period for

each country. GDP per capita is measured in 2005 PPP U.S. dollars per inhabitant. Kuwait and Portugal are excluded from these

plots due to lack of data for the 2006-2008 period.

30

Figure 2: Correlations of Selected Database Measures with GDP

(averages over 2006-2008)

17

Mean Exports per Exporter - GDP

12

Number of Exporters - GDP

ESP

MEX

BRA

BRA

CHL

IRN

MEX

KHM

15

PER

MLI

CRI

BWA

NER

NER

ZAF

NOR

BGD

NZL

DOM ECU

GTM

UGA

TZA

BGR

KEN

YEM

LBN

MKD

SWE

MAR

EST

JOR CMR

SLV

LAO

BFASEN

MWI MUSNIC

14

8

6

MAR

LBN

KEN

EST

GTM

MKD

DOM ECU

SLVCRI

MUS

ALB

TZA

JOR

BWA

NIC

UGA

CMR

SEN

MWI

KHM

YEM

LAO BFA

MLI

CHL

PER

BGD

SWE

BEL ZAF

PAK

COL

EGY

16

Ln Mean Exports per Exporter

10

Ln Number of Exporters

BGR NZL

BEL

TUR

NOR

ESP

TUR

COL

EGY

PAK

IRN

4

13

ALB

23

24

25

26

27

28

23

24

25

Ln GDP

27

28

R-squared=0.24

Number of Products per Exporter - GDP

3

1

Share of Top 5% Exporters - GDP

CHL

NOR

PER

SWE ZAF

SEN

EST

YEM

.6

ALB

BEL

COL

EGY

PAK

BRA

TUR

KHM

EST

LBNGTM

SLV KEN

BWA

SEN

NIC

MKD

MWI

NER MLI BFA

BGD

TUR

BEL

MUS

IRN

1.5

NIC

ZAF

MEX

ESP

NZL

BGR

CRI

DOM

YEM

TZA

CMR

UGA

PER

MAR

MEX

SWE

NOR

CHL

BGD

ECU

IRN

PAK

COL

ESP

ALB

JOR

1

.8

DOM

JOR CMR

BGR

SLVCRIKEN

ECU

LBNGTM

UGA

MAR

2.5

NZL

TZA

2

Ln Number of Products per Exporter

BWA

MLI

MWI

NER

LAO

MUS

BFA

MKD

Share of Top 5% Exporters

26

Ln GDP

R-squared=0.78

.4

KHM

LAO

23

24

25

26

27

28

23

24

25

Ln GDP

26

27

28

Ln GDP

R-squared=0.01

R-squared=0.15

Entry Rate - GDP

2

Number of Destinations per Exporter - GDP

MWILAO

YEM

TZA

.5

BEL

CMR

UGA

IRN

1.5

KHM

MLI BFA

SWE

.5

PER

TUR

ZAF

PAK

ESP

COL

EGY

IRN

.4

BGD

CHL

NOR

LAO

NER

ECU

SEN

ALB

MKD JOR

KEN

ESP

PER

CHL

NOR

BGR

NIC

MEX

KHM

MEX

MAR

SLV

MUS

.3

MWI

MUS

BFA

MLI MKD

NIC

CRI

LBN

NZL

CMR

EST

KEN

GTM BGR MAR

SLVTZA

UGA

YEM

ECU

DOM

Entry Rate

1

SEN JOR

DOM

EST

BWA

TUR

COL

BEL

GTM

CRI

NZL

BGD

ALB

BWA

SWE ZAF

PAK

EGY

0

.2

BRA

23

24

25

26

27

23

28

24

25

Exit Rate - GDP

Survival Rate of Entrants - GDPpc

.6

BGD

KHMPAK

BRA TUR

.4

EST

BWA

UGA

SEN

MKD

NICALB

JOR

MUS

KHM SLV

.3

BGR

ECU

NZL

CRI

.5

BFA

25

26

SEN

ESP

MEX

TUR

NZL

BEL

CHL

KEN

COL

BEL

SWE

EGY

PAK

ZAF

TZA

EST

UGA

ESP

MWI

CMR

BRA

.2

BGD

24

ZAF

CRI

ALB

MKD

SLVPER

MAR

MUS

GTM

COL

ECU IRN

DOM

BWA

MEX

NIC

MLI

NOR

PER

CHL

MAR

GTM

EGY

JOR

LAO

.4

BFA

IRN

.3

CMR

TZA

KEN DOM

.2

Exit Rate

.5

Survival Rate of Entrants

YEM

23

28

R-squared=0.25

MWI

LAO

MLI

27

Ln GDP

Ln GDP

R-squared=0.25

.6

26

27

28

6

Ln GDP

7

8

9

Ln GDPpc

R-squared=0.14

R-squared=0.00

31

10

11

Turnover Rate - GDP

1.2

Net Entry Rate - GDP

.1

LAO

MWI

UGA

YEM

CHL

PER

BEL

ZAF

PAK

NOR SWE

COL

GTM

SLV

CMR

0

DOM

MUS

YEM

NZL

MAR

EGY

BGR

KEN

IRN

TZA

CMR

LAO

TUR

ESP

MLI

MEXBRA

IRN

BFA

DOM

EST UGA

BWA

KEN

ECU

BGR

SEN

MKD

ALB

JOR

NIC

MUS

.6

CRI

ECU

.8

TZA

Turnover Rate

.05

MLI MKD

EST

BFASENKHM

NIC BWA

-.05

Net Entry Rate

1

BGD

JOR

ALB

KHM

ESP

NOR

PER

CHL

MEX

MAR

SLV

GTM

CRI

NZL

BGD

COL

BEL

SWE ZAF

PAK

EGY

TUR

BRA

.4

-.1

MWI

23

24

25

26

27

28

23

Ln GDP

24

25

26

27

28

Ln GDP

R-squared=0.06

R-squared=0.20

Notes: The measures plotted are based on measures in the country-year level dataset averaged across the 2006-2008 period for

each country. GDP is measured in 2005 PPP U.S. dollars. Kuwait and Portugal are excluded from these plots due to lack of data

for the 2006-2008 period.

32

Table 1: Measures by Country (2006-2008 Averages)

Total Exports Number of

(bn USD)

Exporters

ALB

BEL

BFA

BGD

BGR

BRA

BWA

CHL

CMR

COL

CRI

DOM

ECU

EGY

ESP

EST

GTM

IRN

JOR

KEN

KHM

KWT

LAO

LBN

MAR

MEX

MKD

MLI

MUS

MWI

NER

NIC

NOR

NZL

PAK

PER

PRT

SEN

SLV

SWE

TUR

TZA

UGA

YEM

ZAF

Albania

Belgium

Burkina Faso

Bangladesh

Bulgaria

Brazil

Botswana

Chile

Cameroon

Colombia

Costa Rica

Dominican Republic

Ecuador

Egypt

Spain

Estonia

Guatemala

Iran

Jordan

Kenya

Cambodia

Kuwait *

Laos

Lebanon

Morocco

Mexico

Macedonia

Mali

Mauritius

Malawi

Niger

Nicaragua

Norway

New Zealand

Pakistan

Peru

Portugal *

Senegal

El Salvador

Sweden

Turkey

Tanzania

Uganda

Yemen

South Africa

Average - developing countries

Median - developing countries

Average - all countries

Median - all countries

Number of

Exporters

per Capita

Mean

Exports per

Exporter

('000s USD)

Median

Number of Number of

Exports per Share of Top

Products per Destinations

Exporter 5% Exporters

Exporter per Exporter

('000s USD)

1.1

309.1

0.5

12.4

12.9

165.4

4.6

60.9

1.7

19.1

8.7