Presentation slides

advertisement

Competition for Attention

Pedro Bordalo, Nicola Gennaioli, Andrei Shleifer

June 2013

1 / 35

Introduction

I

Strategy and marketing scholars stress the importance of

drawing consumer attention to differentiated attributes (Levitt

1983, Rangan and Bowman 1992, Mauborgne and Kim 2005)

I

I

In some markets, such as fashion goods or business class

travel, consumers focus on quality rather than price. Firms

advertise quality (Singapore Airlines, Nordstrom’s).

In other markets, such as fast food, regular air travel, or

standard home goods, consumers seem focused on prices.

Firms advertise low prices (Southwest Airlines, Walmart).

I

Standard economic models treat quality and price

symmetrically. There is a gap between how business

strategists and economists think about competition.

I

We capture the focus on quality or price by assuming that

consumers are salient thinkers. We study the implications of

this assumption for market equilibrium.

2 / 35

Introduction

I

I

“Salient Thinking” (BGS 2012):

I

Consumers focus on, and overweight, product attributes that

are salient, or stand out, in the choice context.

I

Salient attribute is the dimension – quality or price – that

varies most across the goods in the choice context.

BGS (2012) show that salience provides intuitive account of:

I

Puzzles in consumer choice: context dependent WTP,

violations of IIA (e.g., decoy effects).

I

Empirical patterns, such as asymmetric sales, preference for

low deductible insurance policies, and time variation in demand

for gas quality.

3 / 35

Introduction

Applying this idea to a standard model of competition, we find:

I

When selling to salient thinkers, firms compete for consumers’

attention. Firms choose qualities and prices to render salient

their advantage relative to their competitor.

I

I

Two types of equilibria: quality-salient and price-salient.

I

I

I

Attention Externality: strategic positioning of one product

affects how all other products are perceived.

In quality-salient equilibria, consumers are too sensitive to

quality and quality is over-provided.

In price-salient equilibria, consumers are too sensitive to price

and quality is under-provided.

The cost structure determines salient attribute in equilibrium:

I

I

Equilibria are quality-salient when average costs of quality are

high, and price-salient when average costs of quality are low.

This allows us to think about innovation, viewed as a change

in costs. Shift from price- to quality- salient equilibrium

requires a drastic increase in quality by the innovating firm.

4 / 35

Related work

I

Bounded rationality and IO (Ellison 2006, Spiegler 2011).

I

I

I

Consumers’ consideration set can be manipulated by firms

(Ellison and Ellison 2009, Spiegler and Eliaz 2011, Hefti 2012)

Goods’ attributes may be shrouded, or difficult to compare

(Gabaix and Laibson 2006, Ellison and Ellison 2009, Spiegler

and Piccione 2012).

Inattention and consumer demand.

I

I

Rational inattention: Gabaix (2012), Matějka and McKay

(2012), Persson (2012).

Context-dependent decision weights: Hogarth, Einhorn (1990),

Azar (2008), Cunningham (2012), Dahremöller and Fels

(2012), Koszegi and Szeidl (2013).

5 / 35

Setup: Firms

I

I

Two firms, 1 and 2. Each firm k = 1, 2:

I

produces a good with quality qk at a cost ck (qk ).

I

sets price pk ≥ ck (qk ).

Qualities and prices are set competitively in a two stage game:

I

in the first stage, each firm k makes costless commitment to

produce quality qk ∈ [0, +∞)

I

in the second stage, firms set optimal prices given quality (and

cost) committed to in first stage.

I

Qualities and prices are measured in utils and known to the

consumers.

6 / 35

Setup: Consumers

I

Measure 1 of identical consumers with unit demand.

I

Consumers inflate the weight associated to the attribute

perceived as salient in the choice context:

qk − δpk if quality is salient

S

δq − pk if price is salient

u (qk , −pk ) =

k

qk − pk if equal salience

I

For δ = 1, consumers have standard preferences.

For δ < 1, consumers overweight the salient attribute

(we call them salient thinkers).

I

Rank based weighting allows for simple functional forms that

highlight the properties of salience.

7 / 35

Salience of Attributes

I

Let x be the average value of attribute x in the choice set C .

I

The salience of attribute value xk for good k in C is measured

by a salience function σ(xk , x) that satisfies:

I

Ordering: if [xk0 , x 0 ] is a subset of [xk , x], then

σ(xk , x) > σ(xk0 , x 0 ).

I

Diminishing Sensitivity: for any > 0,

σ(xk + , x + ) < σ(xk , x).

I

I

These properties capture Weber’s law.

As in BGS (2012), we balance these properties by assuming

scale invariance:

σ(αxk , αx) = σ(xk , x), for any α > 0

I

Salience increases in percentage difference between xk and x.

8 / 35

Price Competition (exogenous quality)

I

Price competition stage: firm k = 1, 2 produces given quality

qk at given cost ck . Each firm k sets price pk .

I

I

Rational Benchmark: the firm creating a larger surplus qk − ck

captures the entire market and makes a profit equal to the

differential surplus created. If q1 − c1 = q2 − c2 there are no

profits in equilibrium (Bertrand competition).

To highlight the role of salience we assume:

Assumption A.1:

I

I

I

δ(c1 − c2 ) < q1 − q2 < 1δ (c1 − c2 )

When prices are equal to costs, the consumer chooses the

good with a salient advantage.

This implies that a firm can capture the market by rendering

its advantage salient.

Assumption holds iff the two firms produce sufficiently similar

surpluses qk − ck .

9 / 35

Salience and Competitive Pricing

I

Let us determine salience. The consumers’ choice set is

C = {(q1 , −p1 ), (q2 , −p2 )}

I

The average level of attributes (or reference good) (q, −p) is

equal to:

q=

I

q1 + q2

2

and p =

p1 + p2

2

The salience of quality for good (qk , −pk ) in context C is

measured by σ(qk , q), that of price by σ(pk , p).

10 / 35

The special role of the quality/price ratio

I

Let q1 ≥ q2 and p1 ≥ p2 (will hold in equilibrium). Then,

scale invariance of the salience function implies that:

I

The advantage of good 1 (Quality) is salient if

σ (q1 , q) > σ (p1 , p), namely if:

q1

p1

>

q

p

I

I

q

q1

q2

> >

p1

p

p2

The advantage of good 2 (Price) is salient if

σ (q2 , q) < σ (p2 , p), namely

q

p

<

q2

p2

I

or

or

q2

q

q1

> >

p2

p

p1

The same attribute is salient for both goods.

A good’s advantage is salient iff the good has a higher

quality-price ratio than its competitor.

11 / 35

Salience and Competitive Pricing

It is easy to incorporate salience into a firm’s optimal strategy.

I

A firm captures the market when its advantage is salient.

I

If firm 1 finds it profitable to produce, then the optimal price

p1 at which it captures the market solves:

max

p1 ≥p2

p1 − c1

s.t. q1 − δp1 ≥ q2 − δp2 ,

q1 /p1 ≥ q2 /p2 .

I

Cutting price p1 increases consumer surplus but also helps

satisfy the salience constraint.

I

Additional effect of price cuts: the consumer is willing to pay

more for good 1.

12 / 35

Salience and Competitive Pricing

I

If instead firm 2 finds it profitable to produce, then its optimal

price p2 solves:

max

p2 ≤p1

s.t.

p2 − c2

δq2 − p2 ≥ δq1 − p1 ,

q2 /p2 ≥ q1 /p1 .

I

Cutting price p2 increases consumer surplus but also helps

satisfy salience constraint.

I

Additional effect of price cuts: the consumer is willing to pay

more for good 2.

13 / 35

Salience and Competitive Pricing: Two Remarks

I

I

Salience creates an ”attention externality”:

I

If firm 1 cuts p1 , it makes quality salient for both goods,

causing a relative undervaluation of good 2.

I

If firm 2 cuts p2 , it makes price salient for both goods, causing

a relative undervaluation of good 1.

Salience favors the firm with higher quality to price ratio, i.e.

the lower average cost of quality.

I

Salience constraint for winning firm k is pk ≤ qk · (c−k /q−k ).

Thus equilibrium profits satisfy:

ck

c−k

−

.

pk − ck ≤ qk ·

q−k

qk

These effects can either dampen or magnify competitive forces.

14 / 35

Salience and Competitive Pricing

Under A.1, pure strategy equilibria under price competition satisfy:

I

if qc11 > qc22 , quality is salient, the consumer buys the high

quality good 1, and firm 1 makes positive profits.

I

if qc11 < qc22 , price is salient, the consumer buys the low quality

good 2, and firm 2 makes positive profits.

I

if qc11 = qc22 , quality and price are equally salient, the consumer

buys the good delivering the highest (rational) surplus

qk − ck , and both firms make zero profits.

15 / 35

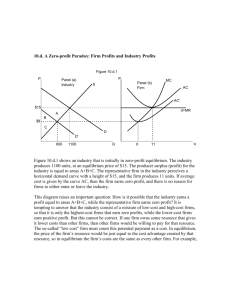

Price Salient vs Quality Salient Equilibria

I

The firm with the lowest average cost of quality can set a

price that renders its best attribute salient.

I

I

Salience creates two types of equilibria:

I

I

I

To attract the consumer’s attention, the losing firm would

have to drastically reduce its price (below cost).

Quality-salient: consumers focus on quality and pay less

attention to prices. This resembles de-commoditized markets.

Price-salient: consumers neglect quality differences and focus

on prices. This resembles commoditised markets.

In both equilibria, profits can be above or below the rational

benchmark. Salience reduces profits when the firms’ average

costs are similar and boosts profits otherwise.

I

In price salient equilibria, the low quality firm can make

abnormal profits because consumers neglect the higher quality

of its competitor.

16 / 35

Salience and Quality Choice

I

Consider now stage 1 of the game, where each firm k sets

quality qk . Firms then set optimal prices given qk , ck (qk ).

I

Assume convex costs, ck (q) = vk (q) + Fk , s.t. v 00 (q) > 0.

I

I

Vary separately the marginal and the average costs of quality

(which affect the salience constraint).

Firm 1 has weakly lower costs:

0 < v1 (q) ≤ v2 (q), 0 < v10 (q) ≤ v20 (q) and 0 ≤ F1 ≤ F2

I

Rational Benchmark:

I

I

I

For firm k, it is (weakly) optimal to maximize surplus

qk − ck (qk ), setting qk∗ s.t. ck0 (qk∗ ) = 1.

If v1 (q) = v2 (q) = v (q), then q1∗ = q2∗ = q ∗ s.t. v 0 (q ∗ ) = 1.

Firm 1 captures the market (and makes profits) iff F1 < F2 .

If v1 (q) < v2 (q), firms set q1∗ > q2∗ .

Firm 1 captures the market and makes positive profits.

17 / 35

Salience and Quality Choice

I

To develop intuition when consumers are salient thinkers,

consider the case in which firms have identical costs:

c1 (q) = c2 (q) = v (q) + F .

I

Suppose now that both firms are at the rational equilibrium,

providing quality q ∗ at cost c(q ∗ ), where c 0 (q ∗ ) = 1.

I

We ask:

Does firm 1 have incentive to move away from surplus

maximizing quality q ∗ (assuming firm 2 does not respond)?

I

Generically, it does.

18 / 35

Salience and Quality Choice

I

Quality reduction: q 0 = q ∗ − ∆q at cost c 0 = c(q ∗ ) − ∆c

I

New product is successful iff its lower price is salient, namely

q∗

∆c

c(q ∗ )

q ∗ − ∆q

>

⇔

>

c(q ∗ ) − ∆c

c(q ∗ )

∆q

q∗

I

Quality increase: q 0 = q ∗ + ∆q at cost c 0 = c(q ∗ ) + ∆c

I

New product is successful iff its higher quality is salient, namely

q ∗ + ∆q

q∗

∆c

c(q ∗ )

>

⇔

<

c(q ∗ ) + ∆c

c(q ∗ )

∆q

q∗

I

Depending on the relationship between marginal and average

cost at the rational benchmark, salience creates incentives to

increase or reduce quality provision.

19 / 35

Salience and Quality Choice

Intuition:

I

If marginal cost of quality at rational level q ∗ is high (relative

to average cost), a small quality reduction allows for a large

price cut.

I

I

Attention externality: price is salient for both products and

firm 1 extracts profits by causing a large relative

undervaluation of its (more expensive) competitor.

If marginal cost of quality at rational level q ∗ is low (relative

to average cost), a small price hike allows for a large quality

increase.

I

Attention externality: quality is salient for both products and

firm 1 extracts profits by causing a large relative overvaluation

of its (higher quality) product.

20 / 35

Equilibrium with Identical Firms

I

When firms have identical costs, the unique pure strategy

equilibrium is symmetric, and the firms share the market:

− v (q)

q if F > F ≡ q/δ

S

S

S

b if F ∈ F , F

q2 = q1 = q =

q

q if F < F ≡ qδ − v (q)

b = arg min c(q)/q.

where c 0 (q) = 1/δ, c 0 (q) = δ, and q

I

Since equilibrium is symmetric, quality and price are equally

salient, so goods are correctly valued.

I

Yet, for δ < 1, provision of quality is inefficient, c 0 (q S ) 6= 1.

21 / 35

Equilibrium with Identical Firms

I

Whether quality is over or under provided depends on unit

cost of quality F .

I

Salience makes firms unwilling to deviate to efficient level q ∗ .

I

I

I

If q S > q ∗ , reducing quality would make lower quality salient

(because F is high, so average costs are larger than marginal

costs at q ∗ ).

If q S < q ∗ , increasing quality would make higher price salient

(because F is low, so marginal costs are higher than average

costs at q ∗ ).

For δ = 1, quality provision q S coincides with rational

benchmark q ∗ .

22 / 35

Identical Firms: the Case of Quadratic Costs

I

I

Suppose that c(q) = c · q 2 /2 + F .

provision is:

1/δc if F

q

2F

if F

qS =

c

δ/c if F

Equilibrium quality

>

∈

<

1

2δ 2 c

h

δ2

1

2c , 2δ 2 c

i

δ2

2c

Comparative statics:

I

Quality provision q S decreases with marginal cost of quality c

(as in the rational case).

I

Quality provision q S increases with unit cost of quality F . In

the rational case δ = 1, quality does not depend on unit costs,

q ∗ = 1/c.

23 / 35

Identical Firms: the Case of Quadratic Costs

In more detail: the equilibrium quality provision q S

I

I

increases with unit cost of quality F . This is due to the

diminishing sensitivity property of salience:

I

When F is low, costs (and prices) are low. Small price

differences are salient, inducing firms to cut costs and quality.

I

When F is high, costs (and prices) are high. Small extra costs

are not noticeable, inducing firms to boost quality.

decreases with marginal cost of quality c.

I

The quality that minimises average cost decreases with c (as

does the quality that maximizes perceived surplus).

I

Diminishing sensitivity: the shift in quality from a shock in c is

larger the higher is F .

24 / 35

Low Cost vs High Cost Equilibria

I

Sellers of expensive goods (high end cars, fancy hotels)

compete on quality, providing visible quality add-ons.

I

I

Sellers of cheap goods (low end clothes, fast food outlets)

compete on price, and cut on product quality if that allows

them to offer substantially lower prices.

I

I

Quality add-ons help make overall product quality salient, and

the profit margin associated with them can be hidden behind

the high cost of the baseline good.

By focusing consumers’ attention on costs, firms providing

cheaper goods are able to make abnormal profits.

In equilibrium, profits disappear as competing firms adopt the

same add-on or quality reduction strategies, despite the fact

that they are providing inefficient levels of quality.

25 / 35

Innovation

I

We model innovation as a change in product characteristics

and market equilibrium in response to a cost shock.

I

We start from a market in a long run symmetric equilibrium.

I

In this setting, we consider two types of shocks:

I

Industry wide cost shock, that preserves symmetry of cost

structures across firms (e.g. shock in price of inputs).

Specifically, we consider a drop in the unit fixed cost F .

I

Firm specific shocks, that give one firm a cost advantage (e.g.

a technical breakthrough). Specifically, we consider a drop in

the marginal cost c1 at which firm 1 can provide quality.

I

We consider other types of shocks in the paper.

26 / 35

Innovation: Industry wide cost shock

I

Suppose that initiallypF is in the intermediate range, so that

in equilibrium q S = 2F /c.

I

After the drop in unit costs F for all firms, quality provision

strictly decreases:

I

Price cuts can be very salient, so firms sharply cut price down

to cost.

I

Consumers focus on prices, inducing firms to also cut quality

and reducing prices even further.

I

A large uniform drop in F changes the (symmetric) equilibrium

from quality over-provision to potentially severe quality

under-provision.

27 / 35

Innovation: Firm-specific reduction in marginal cost

Let firm 1 receive a beneficial shock to its marginal cost,

c1 < c2 = c

I

If shock is large, c1 < c/2, firm 1 boosts its quality and price.

I

I

If the cost shock is small, c1 > c/2, then hiking up quality

causes a sizeable increase in price.

I

I

A drastic reduction in variable costs allows for a large and

salient quality upgrade, q1 > q S , so firm 1 captures the market.

If F < Fb , firm 1 keeps quality at q S and simply lowers price.

Small cost innovation: price competition among homogeneous

goods!

In either case, firm 2 has no incentive to deviate from the

symmetric equilibrium q S .

28 / 35

A commodity magnet:

Consider a firm locked in a commoditized (symmetric) price salient

market.

I

A drastic innovation that allows the firm to provide sufficiently

higher quality than its competitors, and at sufficiently low

price, can trigger a shift to a quality salient equilibrium.

I

Small cost reducing innovations neither beat the “commodity

magnet”, nor lead to marginal quality improvements. They

just translate into (marginally) lower prices.

I

In contrast, in the standard model with δ = 1, a reduction in

marginal costs of quality always leads to a (surplus increasing)

boost in quality provision.

29 / 35

Applications

We now illustrate the model with three innovation episodes:

I

Deregulation in the airline industry: uniform reduction in

operating costs F .

I

Rise of the premium coffee market: one firm (Starbucks)

provides much higher quality at a “reasonable” price, drastic

reduction in marginal costs c.

I

Financial innovation: one firm uses financial engineering

techniques to increase yield at small extra risk.

30 / 35

Application I: Deregulation and commoditization of Airlines

Shed light on the rise of low cost airlines, as a consequence of

deregulation of the airline industry.

I Deregulation of the airline industry enabled carriers to freely

set routes and prices, but also freed entry into the industry.

Major reduction in the costs F of operating an airline.

I

I

Pre-deregulation, the market was in quality salient equilibrium:

I

I

I

In this case, our model predicts a transition from a high quality

equilibrium to a low quality equilibrium.

high operating costs rendered small price differences among

airfares non salient (though price competition was possible).

Airlines competed by offering extra services to consumers.

Deregulation: opportunity to implement salient price cuts.

I

I

New entrants, such as Southwest, became low cost carriers.

Traditional carriers, burdened with legacy costs, were unable to

respond. The salience of low prices placed these companies at

a competitive disadvantage, forcing many into bankruptcy.

31 / 35

Application II: decommoditization of the coffee market

Provide a rationale for the rise in quality of certain consumer

products, such as premium coffee.

I

Industry initially provided drip coffee at low prices

(e.g. neighborhood diner)

I

I

Starbucks discovers how to boost quality at reasonable higher

costs, including improving taste, consistency and in-shop

environment. Large reduction in variable cost c1 .

I

I

I

Locked in price-salient equilibrium with low operating costs.

Small innovations translate into price cuts (e.g. free refills).

Given drastic reduction in the marginal cost of producing

quality, Starbucks boosts the quality of its product as well as

its operating costs, but makes the product’s quality salient.

By drawing consumers’ attention to the higher quality of its

product, Starbucks was able to charge much higher prices.

Decommoditization as a shift from price salient to quality

salient equilibrium.

32 / 35

Application III: Financial Innovation

Provide a rationale for investors’ reach for yield as new financial

assets are introduced.

I

Quality of financial asset is net return R, cost of financial asset

is risk v (given exogenously). Rational valuation is R − v .

I

I

I

Firms produce return out of risk and compete in fees.

Rational benchmark: zero fees.

Innovation: one firm reduces the extra risk necessary to

produce extra return, and can update its asset.

I

I

Successful if baseline level of returns is low: when investments

yield 1%, having an extra 0.5% is very salient, particularly

because risk increases less in % terms (due to innovation).

Investors focus on return and neglect extra risk. Risk taking is

excessive, and innovating firm makes excess profits. Innovation

can spread.

33 / 35

Possible Extensions

We explore the robustness of the results to several extensions of

our framework:

I

Heterogeneity in salience.

I

I

I

Attribute salience has stochastic component and varies across

consumers.

Generates “smooth” demand functions. Firm with lower

average costs in equilibrium captures larger share of the

market, and makes higher profits.

Asymmetric equilibria.

I

I

Closely mirrors innovation case, which survives as a refinement.

New case: when firm 1 has small cost advantage, it may

produce strictly lower quality to make its lower price salient.

34 / 35

Open issues

I

Entry and dynamics of innovation.

I

I

I

If incumbent firms are in price salient equilibria (with low

prices), salience hampers quality increasing innovations, while

it facilitates price reducing innovations.

Horizontal differentiation.

I

Firms segment the market between consumers attracted to

different attributes, drawing attention away from price, thus

earning higher profits.

I

This logic may shed light on political competition, but also on

the competitive forces leading to “shrouded” attributes

(Gabaix and Laibson 2006) or “irrelevant” attributes

(Carpenter, Glazer and Nakamoto, 1994).

Advertising.

I

Purpose is to inform about, and draw attention to, the

products attributes the seller wants consumers to think about.

I

Simultaneously informative and persuasive.

35 / 35