Globalization and the Natural Limits of Competition

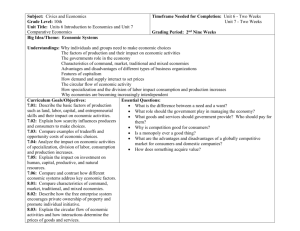

advertisement