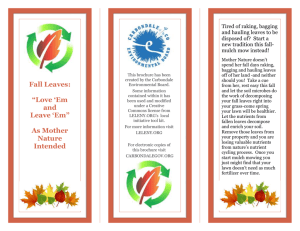

Alabama Smart Yards - Alabama Cooperative Extension System

advertisement