Investigation of Travel Behaviour of Visitors to Scotland

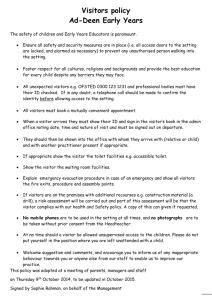

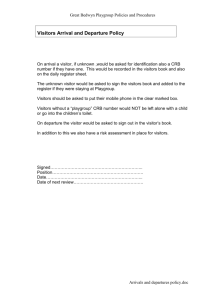

advertisement