In This Issue:

How to Allocate Time & Effort

Page 9

Management Time - Who’s Got the Monkey?

Page 12

Time Bandits: How they are Created.....

Page 20

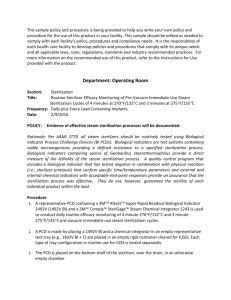

Back to Basics - Steam Sterilization

Page 39

The

of the

the Laboratory

LaboratoryAnimal

AnimalManagement

Management

Association,

2013

The Journal

Journal of

Asso

ciation, 2009

The Lama Review - Page 1

Volume

25 › 1Issue 1

Volume

22 › Issue

Ancare Bottle Filler

Fill It.

Type 316 stainless steel construction throughout.

Removable nozzles for easy cleaning/replacement.

Adjustable header height.

Includes full backsplash, fully compatible with high purity

urity water.

Other models, hand held, and custom configurationss available.

Ancare Water Bottles

Introduced plastic bottles to LAS in 1966

Many sizes and shapes available to accomodate a

wide range of cages and species

Available in several different plastics

Ancare

ncare Bottle Baskets

All welded

welded, stainless steel rod construction

Standard stainless steel rod lid, optional wire mesh

Extension allows stacking of full bottles with stoppers and

tubes in place

Other models and custom versions available

Better products. Better science.

Page 2 - The Lama Review

Ancare Corp.

P.O. Box 814, 2647 Grand Avenue, Bellmore, NY, 11710

T: 800.645.6379/516.781.0755, F: 516.781.4937

ancare.com

facebook.com/AncareCorp

youtube.com/AncareCorp

ObjecƟves of the

Laboratory Animal Management

AssociaƟon

• To promote the dissemination of ideas, experiences, and knowledge

• To encourage continued education

• To act as spokesperson

• To actively assist in the training of managers

This publication contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been

specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available to

advance understanding of ecological, political, economic, scientific, moral, ethical,

personnel, and social justice issues, etc. It is believed that this constitutes a “fair use”

of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C Section 107, this material is distributed without

profit to those who have expressed a prior general interest in receiving similar information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material

for purposes of your own that go beyond “fair use,” you must obtain permission from

the copyright owner.

For more information concerning The LAMA Review, please contact the Editor in Chief,

Ted Plemons at e-mail: lamareview@gmail.com

Change of Address:

Attention, Members. Are you moving? To ensure that you receive your next issue of

The LAMA Review, please send your change of address to:

The LAMA Review

Judy Hansen

Laboratory Animal Management Assn.

Membership Manager

7500 Flying Cloud Drive - Suite 900

Eden Prairie, MN 55344

952-253-6235 ext 6077

jhansen@associationsolutionsinc.com

LAMA Review advertising rates and information are available upon request via email, phone, or

mail to:

Jim Manke, CAE

Direct: 952-253-6084

LAMA Review

7500 Flying Cloud Drive, Suite 900

Eden Prairie, MN 55344

jrmanke@associationsolutionsinc.com

Fax: 952-835-4474

Employment opportunity ads are FREE

The Lama Review - Page 3

T H E

2012-2013 Executive

Committee Officers

L A M A

PRESIDENT

Tracy Lewis, LATG,CMAR

Andover, MA

VICE PRESIDENT

Pamela Straeter, RLATTG

Kenilworth, NJ

VICE PRESIDENT ELECT

Wayne DeSantis

West Chester, PA

Volume 25, No.1

PAST-PRESIDENT

Lisa Osborne, RLATG, CMAR

El Paso, TX

In This Issue:

7

President Message

9

How to Allocate Time & Effort

12

Management Time:

Who’s Got the Monkey?

18

Dealing with Difficult People

20

SECRETARY/TREASURER

Howard Mosher

Killingworth, CT

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Jim Manke, CAE

Eden Prairie, MN

in a changing world

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Lisa Secrest- Alexandria, VA

Dorothy Loud - Mt. Vernon, IN

Leah Curtin - Framingham, MA

2012 LAMA Review

Editorial Staff

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Ted Plemons

Bethesda, MD

Time Bandits

How they are created, Why they are Tolerated.......

29

Acknowledge People w/o Turning them Off

39

Back to Basics: Steam Sterilization

Principles & Common Mistakes

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

MANAGING EDITOR

Evelyn Hilt

Lafayette, IN

EDITORIAL

ADVISORY BOARD

Steve Baker

Framingham, MA

Gail Thompson

Wheatland, WY

Staff Contacts

45

Jim Manke, CAE

Executive Director

(952) 253-6084

Innovations

Using VHP to Turn your Cage & Rack Washer into......

Advertiser Listing

Inside Front Cover

Across from TOC

Page 31

Page 4 - The Lama Review

Ancare

Purina Lab Diet

Pharmacal

Kathi Schlieff

Meeting Manager

(952) 253-6235 X6085

Judy Hansen

Membership &

Development Manager

LAMA Review Coordinator

(952) 253-6240 x6077

±7YGGIWWJYPVIWIEVGL

FIKMRW[MXLGSRWMWXIRX

RYXVMXMSRUYEPMX]TVSHYGXW

ERHVIPMEFPIVIPEXMSRWLMTW²

As a LabDiet Nutritionist, I assist researchers in formulating

BTRSNLCHDSRNQRDKDBSHMF@CHDSSG@SRTHSRSGDHQRODBHƥBMDDCR

I also help maintain the LabDiet products to ensure we are

providing a consistent product based on Constant Nutrition ®

®

®

(ƥMCHSQDV@QCHMFSNG@UDHMCDOSGBNMUDQR@SHNMRVHSGQDRD@QBGDQR@MCOQNUHCD

SGDLVHSGMDVHMENQL@SHNMSG@SL@XADMDƥSSGDHQVNQJ

®

+@A#HDS HRATHKSNM@ENTMC@SHNMNESQTRS@MCQDRODBS@MC(L@JDHSLX

ODQRNM@KFN@KSNQDƦDBSSGDRD@SSQHATSDRHMLXVNQJ!XBQD@SHMF@ONRHSHUD

Q@OONQSVHSGLXBKHDMSR(GDKOSGDL@BGHDUDETKƥKKHMFQDRTKSR

Brittany Vester Boler, PhD

Animal Nutrition Technical

Services Consultant – Purina

Animal Nutrition

JOGP!MBCEJFUDPNtXXX-BC%JFUDPN

The Lama Review - Page 5

Did you know?

In the Laboratory Animal community, publishing a

professional journal is an essential part of advancing

your career. Submitting an article to the LAMA Review

provides an opportunity to be published in a professional journal. This is a great opportunity to share

your research knowledge and accomplishments.

Imagine your journal impacting and influencing the laboratory animal management practices!

The LAMA Review provides important information on industry’s advancements and developments to

those involved in the Laboratory Animal field with emphasis in management.

The LAMA Review is published electronically each quarter and combines short columns with longer

feature articles. Each issue focuses on significant topics and relevant interest to ensure a well-rounded

coverage on laboratory management matters.

Submitting an article

Choose an interesting topic that has the potential to benefit the Laboratory Animal Management community. Write the article that you would like to see published in the journal. Be sure to include multiple

sources to support your research and accurately cite references.

Submit your article to Review via email lamareview@gmail.com

Benefits of publishing

The LAMA Review is the official journal of the Laboratory Animal Management Association, which is

committed to publishing high quality, independently peer-reviewed research and review material.

The LAMA Review publishes ideas and concepts in an innovative format to provide premium information for laboratory Animal Management in the public and private sectors which include government

agencies.

A key strength of the LAMA Review is its relationship with the Laboratory Animal management community. By working closely with our members, listening to what they say, and always placing emphasis

on quality. The Review is finding innovative solutions to management’s needs, by providing the necessary resources and tools for managers to succeed.

Article Guidelines

Submissions of articles are accepted from LAMA members, professional managers, and administrators

of laboratory animal care and use. Submissions should generally range between 2,000 and 5,000. All

submissions are subject to Submissions are accepted for the following features of the LAMA Review:

o

o

o

o

o

Original Articles

Review Articles

Job Tips

Manager’s Forum

Problem Solving

Page 6 - The Lama Review

President s Message

“How did it get so late so

soon? It’s night before it’s

afternoon. December is

here before it’s June. My

goodness how the time

has flewn. How did it get

so late so soon?”

― Dr. Seuss

Incredible as it may seem, the

LAMA year is coming to a close! Isn’t it funny that our

administrative year has us at an endpoint when the

season of spring is bringing new beginnings? Maybe

that isn’t so odd after all, when we really stop and think

about it.

While my presidency is coming to an end, there are a

number of new beginnings. In the near future, we will

be gathering in Clearwater for our annual LAMA-ATA

meeting. Your program committee has worked tirelessly

and I can assure you that they have put together a

program that is full of timely topics as well as a bit of fun.

You will be seeing a lot of promotion for the program in

the very near future…keep your eyes open! While we

are in Clearwater, we will recognize the winner of last

year’s Ron Orta award. That presentation will occur

on Wednesday morning. We will also present awards

to some very well deserving managers, and announce

the results of our recent elections. It will be my distinct

honor to pass the gavel along to Pam Straeter who is

indeed one of the best facility managers I have ever had

the pleasure with which to work. Moreover, I’m so proud

that I can call her my friend.

As someone who has worked on program committees,

(for LAMA, for AALAS, for local and regional branch

events) I can say that the quality of the program is

extremely important to me. LAMA is fortunate to have a

core of talented individuals in its’ membership; and they

are not shy about presenting their ideas! That is one of

the best perks of being an active LAMA member. The

network that we have puts answers at our fingertips…

through email, LinkedIn, phone conversations and

certainly face to face meetings. If you can’t get the

answer through LAMA, the answer might not be there at

all!

Another important event that will take place during the

annual meeting is the LAMA Foundation Auction. The

silent and “not so silent” auction is THE main fundraiser

for the Foundation each year. We have a lot of fun, but

we also raise money for the Foundation, which in turn

- Tracy Lewis

funds award recipients resources to attend ILAM or

other management training.

While there will be plenty of networking and learning,

we also need to take some time to de-stress. One way

that we will be doing that is during the Fun Fair. As has

been tradition, we will have some willing (and maybe not

so willing) volunteers organize participants into teams

for some friendly competition. Funds raised during this

event will be presented to a local charity on Friday. This

is how LAMA pays it forward.

If I may take just a little more of your time, I’d like to

detail what the Education Committee has accomplished

this year.

NCAB: Technician to Supervisor/Management 101

Charles River (Private Session). CMII

AALAS: AR preparatory wkshop.

D4 Leadership Training

D4 AR preparatory wkshop

FESSACAL

1. Vivarium Operations and Design

2. Lean Mgmt

3. Decontamination Procedures

4. Lab Animal Mgmt Panel Discussion

On the horizon:

LAMA / ATA AR preparatory wkshop

QUAD: CM1, 2, or 3

I would like to take a moment to thank Steve Baker

as he steps down as the chair of this committee. It’s

dedicated people like Steve who work tirelessly to

further the LAMA offerings to our members.

I’m going to close as I have all of my prior letters to you.

LAMA exists because of the hard work and dedication of

the members of committees and the board. The more

members that are involved, the more that we will be

able to offer! Get involved! We’re always looking for

volunteers to continue to move LAMA forward.

See you in Clearwater!

“It is good to rub and polish our brains against

that of others.”

Michel de Montaigne

The Lama Review - Page 7

From The Editor s Cube.....

For me, the New Year is the beginning of a slate that has been wiped clean, or a fresh

start especially if 2012 was not so wonderful. I always look back and have to wonder

where does all the time go? Going into 2013, how many of us have made a New Year’s

resolution to be more organized? For me, a little more organization would go a long way

to making my home and work life run a bit more smoothly.

Where Does All the Time Go?

-Ted Plemons- Editor

As managers, we are under increasing pressure to boost productivity. There never seem

to be enough hours in the week to get everything accomplished. One of my biggest

problems is trying to do too many things in too little time, trying to satisfy all the requests.

With such high demands, many times I find myself at my desk trying to focus on the task

only to find that my mind is wandering.

Despite my best intentions, I just cannot concentrate. I’m sure that we have all been in

this familiar, frustrating situation. Put simply, we are being asked to do more with fewer

resources. I am pushing myself and the staff to do things differently, to do things better, to make a positive change in the way we operate. Unfortunately, there are no easy

answers; there is no size fits all time-table for managers to follow.

In this issue, I have tried to pull management articles that give us suggestions and tools

to help all of us to become better at managing our time in hopes that we will all examine

our working habits to try to identify ways that we all can become more productive. I

believe St. Francis of Assisi had the correct vision “Start by doing what’s necessary, then

what’s possible, and suddenly we are doing the impossible.”

Page 8 - The Lama Review

“How does he find time to meet with 10 customers a week and make his yearly quota in

the first quarter? I can barely find time to have

five appointments a week and get all my paperwork done correctly and turned in on time.”

A manager ponders about his colleague on the

corporate fast track: “How does she manage

to champion strategic initiatives, network with

executives and only work 40 hours a week?

After a day full of project meetings, the best I

can do is reactively respond to email at night

instead of proactively developing my department.”

Here’s the secret: The colleagues who zoom

ahead of you with seemingly less effort have

an exceptional level of achievement, and I was

fortunate that in my case, it was rewarded with

scholarships and job offers.

The rules changed when I started my own

business more than seven years ago. I realized that doing grade-A work in everything limited my success. At that point, I realized that I

needed to focus more on my strengths.

As Tom Rath wisely explains in his “Strengths

Finder” books, you can achieve more by fully

leveraging your strengths instead of constantly

trying to shore up your weaknesses. I have

realized the importance of purposely deciding where I will invest more time and energy

to produce stellar work and where less-thanperfect execution has a bigger payoff. This has

How to Allocate your

Time & Effort

By ELIZABETH GRACE SAUNDERS

From hbr.org c.2013 Harvard Business School Publishing Corp.

Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate A salesman wonders about

his top co-worker:

learned to recognize and excel at what really

counts – and to aim for less than perfect in

everything else.

It is likely that the highest-producing salesman on your team devotes less than half the

amount of time that you do to fill out paperwork. Yes, his may be sloppy, but no one really

cares because he’s skyrocketing the revenue

numbers. The manager who has caught the

eye of upper management may send emails

with imperfect grammar and decline invites to

tactical meetings. But when a project or meeting really matters, she outshines everyone.

If you’re shocked and feel that this seems

completely unfair, I’m guessing you probably

did very well in school, where perfectionism is

encouraged.

I was a straight-A student from sixth grade

through college graduation and did whatever

it took to produce work at a level that would

please my professors. Admittedly, this strategy

paid off as a student. My perfect GPA signified

had a profound effect on my own approach

to success and my ability to empower clients

who feel overwhelmed.

When I talk with time-coaching clients –

whether they be professors, executives or lawyers – a common theme comes up: They feel

as though they can’t find time to do everything.

And they’re right: No one has time for everything. Given the pace of work and the level of

input in modern society, time management is

dead. You can no longer fit everything in, no

matter how efficient you become.

My time-investment philosophy encourages individuals to see time as a limited resource and

to allocate it in alignment with their personal

definition of success. That leads to a number

of practical ramifications:

• DECIDE WHERE YOU WILL NOT

SPEND TIME:

With a limited budget of time at your disposal,

you will not have the ability to do everything

you would like to do, regardless of your efThe Lama Review - Page 9

ficiency. The moment you embrace that truth, you instantly reduce your stress and feelings of inadequacy.

Professionally, this might mean reducing your involvement in committees; on the personal level, you might

consider hiring someone else to maintain your lawn or

finish up a home-improvement project.

These things need to get done, but you can aim for Blevel work. Optimize activities are those for which additional time spent leads to no added value and keeps

you from doing other, more valuable activities. Aim for

C-level work in these – the faster you get them done,

the better. Most basic administrative paperwork and

errands fit into this category.

• STRATEGICALLY ALLOCATE YOUR TIME:

Setting boundaries on how and when you invest time

in work and in your personal life can help to ensure

that you allocate properly to each category. One of the

most compelling reasons for not working extremely

long hours is that this investment of time resources

leaves you with insufficient funds for activities like

exercise, sleep and relationships.

The overall goal is to minimize the time spent on

optimize activities so that you can maximize your time

spent on investment activities. I’ve found that this

technique allows you to overcome perfectionist tendencies and invest in more of what actually matters,

so that you can increase your effectiveness personally

and professionally.

• SET UP AUTOMATIC TIME INVESTMENT:

On a tactical level, here are a few tips on how you can

put the INO technique into action:

Just like you set up automatic financial investment to

mutual funds in your retirement account, your daily

and weekly routines should make your time investment close to automatic. For example, at work you

could have a recurring appointment with yourself two

afternoons a week to move forward on key projects,

and outside of work you could sign up for a fitness

boot camp, where you would feel bad if you didn’t

show up and sweat three times a week.

• AIM FOR A CONSISTENTLY BALANCED

TIME BUDGET:

Given the ebbs and flows of life, you can’t expect that

you will have a constantly balanced time budget. But

you can aim for having a consistently balanced one.

Over the course of a one- to two-week period, your

time investment should reflect your priorities.

Once you have properly allocated your time, you

also need to approach the work within each category

differently. Trying to get straight A’s keeps you from

investing the maximum amount of time in what will

bring the highest return on your investment. That’s

why I developed the INO technique to help overcome

perfectionism and misallocation of your time. Here’s

how it works:

When you approach a to-do item, you want to consider whether it is an investment, neutral or optimize

activity. Investment activities are areas where an

increased amount of time and a higher quality of work

can lead to an exponential payoff. For instance, strategic planning is an investment activity; so is spending

time, device-free, with the people you love. Aim for Alevel work in these areas. Neutral activities just need

to get done adequately; more time doesn’t necessarily

mean a significantly larger payoff. An example might

be attending project meetings or going to the gym.

Page 10 - The Lama Review

• At the start of each week, clearly define the most

important investment activities and block out time on

your calendar to complete them early in the week and

early in your days. This will naturally force you to do

everything else in the time that remains.

• When you look over your daily to-do list, put an “I,”

“N” or “O” beside each item and then allocate your

time budget accordingly, such as four hours for the “I”

activity, three hours for the “N” activities and one hour

for the “O” activities.

• If you start working on something and realize that

it’s taking longer than expected, ask yourself, “What’s

the value and/or opportunity cost in spending more

time on this task?” If it’s an I activity and the value is

high, keep at it and take time away from your N and O

activities. If it falls into the N category and there’s little

added value, or the O category and spending more

time keeps you from doing more important items,

either get it done to the minimum level, delegate it,

or stop and finish it later when you have more spare

time.

• If you keep a time diary or mark the time you spent

on your calendar, you can also look back over each

week and determine if you allocated your time correctly to maximize the payoff on your time investment.

Elizabeth Grace Saunders is a time coach, founder of Real Life E

Time Coaching & Training and the author of``The 3 Secrets to Effective Time Investment: How to Achieve More Success With Less

Stress.’’) To purchase this article, please visit www.nytsyn.com/

contact and contact your local New York Times Syndicate sales

representative. For customer support, please call 1-800-972-3550

or 1-212-556-5117.

We all have “too much to do.” True? Sure ‘nuf. And that

says a lot of good things about you. That you have “too

much to do” suggests that a lot of people have entrusted

much confidence in you. I mean, people who are drifting

about early each afternoon begging co-workers for

something to do, may not have earned that confidence

we will enjoy. It’s the logical choice.

So let’s say it’s the start of your workweek and you have

a lot of “things to do,” some of which are “Crucial,” some

“Not Crucial.” Intuitively and instinctively you and I want

to be good time managers. Therefore, where does our

attention gravitate towards? Do we focus on the “Crucial”

CRUCIAL v. NOT CRUCIAL

By: Dr. Donald E. Wetmore

from others. And this applies not only in our work lives

but in our personal lives as well.

But this creates a double-edged sword. On the one

hand, it’s great to enjoy the confidence of others. Yet,

having “too much to do” often creates the stresses and

distresses that may reduce your overall productivity.

I divide our responsibilities into two categories: “Crucial”

and “Not Crucial.” Crucial items give us the “biggest

bang for the buck” for the time spent and is the most

productive use of our time. It is the logical use of our

time. “Not Crucial” gives us emotional relief. It’s doing

the little things, the junk mail, desk dusting and the like,

that, while necessary, do not really advance our daily

success very much.

When we accomplish the “Crucial” things in our life

we are doing “business” v “busyness.” We are making

progress versus wheel spinning. Have you ever had

a day when you were busy the whole daylong but

when you got home that night you knew you had not

accomplished a darn thing? (We can fool the world

sometimes but we cannot fool ourselves.)

Doing the Crucial things builds up our self-esteem

and our motivation level. Ever notice when you’ve

had a really productive “Crucial” day how that positive

momentum carried forward into your evening hours?

You are more inclined to do the woodworking, spend

time with the kids, or work on hobbies, when you’ve

had a great day. But when you’ve had one of those “Not

Crucial” days, the motivation and momentum levels are

reduced and when we come home that night, many of

us just want to block out the day with that all important

exercise, “click, click, click,” the sound of the TV remote

device, surfing us through a multitude of channels that

fail to grab our interest.

I really believe that most people, intuitively and

instinctively, want to be good time managers. It makes

sense. The better we manage our time, the more results

or “Not Crucial” tasks? The “Crucial”? Sure! Logic tells

us that. The more “Crucial” things we do, the more

productivity and success we enjoy.

But, you know what? When given a choice between

“Crucial” and “Not Crucial” items, we will almost always

do the “Not Crucial” items and ignore the “Crucial” items

in spite of the fact that we all want to be productive in

our day.

Why?

Because we are driven more by emotion rather than

logic.

You see the “Crucial” items are typically longer and

harder to accomplish. The “Not Crucial” items are

typically quicker and fun and emotionally satisfying.

We need to get over to the “Crucial” side more often to

increase our personal productivity.

Would you like to receive free Timely Time

Management Tips on a regular basis to increase

your personal productivity and get more out of every

day? Sign up now for our free “Time management

Discussion List Just go to: http://www.topica.com/

lists/timemanagement and select “subscribe”. We

welcome you aboard!

Dr. Donald E. Wetmore-Professional Speaker

Productivity Institute-Time Management Seminars

127 Jefferson Street

Stratford, CT 06615

(800) 969-3773

(203) 386-8062

fax: (203) 386-8064

Email: ctsem@msn.com

website: http://www.balancetime.com

Professional Member-National Speakers Association

Copyright 1999 You may re-print the above information in its

entirety in your publication, newsletter, or on your webpage. For

permission, please email your request for “reprint” to: ctsem@

msn.com

The Lama Review - Page 11

Management Time “Who’s Got the Monkey?”

by William Oncken, Jr., and Donald L. Wass

This article was originally published in the

November–December 1974 issue of HBR and

has been one of the publication’s two bestselling reprints ever.

For its reissue as a Classic, the Harvard

Business Review asked Stephen R. Covey to

provide a commentary.

Why is it that managers are typically running

out of time while their subordinates are

typically running out of work? Here we shall

explore the meaning of management time as

it relates to the interaction between managers

and their bosses, their peers, and their

subordinates.

Specifically, we shall deal with three kinds

of management time:

Boss-imposed time—used to accomplish

those activities that the boss requires and that

the manager cannot disregard without direct

and swift penalty.

System-imposed time—used to accommodate

requests from peers for active support.

Neglecting these requests will also result in

penalties, though not always as direct or swift.

Self-imposed time—used to do those things

that the manager originates or agrees to do. A

certain portion of this kind of time,

Page 12 - The Lama Review

however, will be taken by subordinates and

is called subordinate-imposed time. The

remaining portion will be the manager’s own

and is called discretionary time. Self-imposed

time is not subject to penalty since neither

the boss nor the system can discipline the

manager for not doing what they didn’t know

he had intended to do in the first place.

To accommodate those demands, managers

need to control the timing and the content of

what they do. Since what their bosses and

the system impose on them are subject to

penalty, managers cannot tamper with those

requirements. Thus their self-imposed time

becomes their major area of concern.

Managers should try to increase the

discretionary component of their self-imposed

time by minimizing or doing away with the

subordinate component. They will then use

the added increment to get better control

over their boss-imposed and system-imposed

activities. Most managers spend much more

time dealing with subordinates’ problems than

they even faintly realize. Hence we shall use

the monkey-on-the-back metaphor to examine

how subordinate-imposed time comes into

being and what the superior can do about it.

Where Is the Monkey?

Let us imagine that a manager is walking

down the hall and that he notices one of his

subordinates, Jones, coming his way. When the two

meet, Jones greets the manager with, “Good morning.

By the way, we’ve got a problem. You see….” As

Jones continues, the manager recognizes in this

problem the two characteristics common to all the

problems his subordinates gratuitously bring to his

attention. Namely, the manager knows (a) enough

to get involved, but (b) not enough to make the onthe-spot decision expected of him. Eventually, the

manager says, “So glad you brought this up. I’m in a

rush right now. Meanwhile, let me think about it, and

I’ll let you know.” Then he and Jones part company.

Let us analyze what just happened. Before the two

of them met, on whose back was the “monkey”?

The subordinate’s. After they parted, on whose back

was it? The manager’s. Subordinate-imposed time

begins the moment a monkey successfully leaps

from the back of a subordinate to the back of his or

her superior and does not end until the monkey is

returned to its proper owner for care and feeding. In

accepting the monkey, the manager has voluntarily

assumed a position subordinate to his subordinate.

That is, he has allowed Jones to make him her

subordinate by doing two things a subordinate is

generally expected to do for a boss—the manager

has accepted a responsibility from his subordinate,

and the manager has promised her a progress report.

The subordinate, to make sure the manager does

not miss this point, will later stick her head in the

“Get control over the timing and content

of what you do” is appropriate advice for

managing time. The first order of business

is for the manager to enlarge his or her

discretionary time by eliminating subordinateimposed time. The second is for the

manager to use a portion of this newfound

discretionary time to see to it that each

subordinate actually has the initiative and

applies it. The third is for the manager to use

another portion of the increased discretionary

time to get and keep control of the timing and

content of both boss-imposed and systemimposed time. All these steps will increase

the manager’s leverage and enable the value

of each hour spent in managing management

time to multiply without theoretical limit.

manager’s office and cheerily query, “How’s it

coming?” (This is called supervision.)

Or let us imagine in concluding a conference with

Johnson, another subordinate, the manager’s parting

words are, “Fine. Send me a memo on that.”

Let us analyze this one. The monkey is now on the

subordinate’s back because the next move is his, but

it is poised for a leap. Watch that monkey. Johnson

dutifully writes the requested memo and drops it in

his out-basket. Shortly thereafter, the manager plucks

it from his in-basket and reads it. Whose move is

it now? The manager’s. If he does not make that

move soon, he will get a follow-up memo from the

subordinate. (This is another form of supervision.) The

longer the manager delays, the more frustrated the

subordinate will become (he’ll be spinning his wheels)

and the more guilty the manager will feel (his backlog

of subordinate-imposed time will be mounting).

Or suppose once again that at a meeting with a third

subordinate, Smith, the manager agrees to provide all

the necessary backing for a public relations proposal

he has just asked Smith to develop. The manager’s

parting words to her are, “Just let me know how I can

help.”

Now let us analyze this. Again the monkey is initially

on the subordinate’s back. But for how long? Smith

realizes that she cannot let the manager “know” until

her proposal has the manager’s approval. And from

experience, she also realizes that her proposal will

likely be sitting in the manager’s briefcase for weeks

before he eventually gets to it. Who’s really got the

monkey? Who will be checking up on whom? Wheel

spinning and bottlenecking are well on their way

again.

A fourth subordinate, Reed, has just been transferred

from another part of the company so that he can

launch and eventually manage a newly created

business venture. The manager has said they should

get together soon to hammer out a set of objectives

for the new job, adding, “I will draw up an initial draft

for discussion with you.”

Let us analyze this one, too. The subordinate has

the new job (by formal assignment) and the full

responsibility (by formal delegation), but the manager

has the next move. Until he makes it, he will have the

monkey, and the subordinate will be immobilized.

Why does all of this happen? Because in each

instance the manager and the subordinate assume

at the outset, wittingly or unwittingly, that the matter

The Lama Review - Page 13

under consideration is a joint problem. The monkey in

each case begins its career astride both their backs.

All it has to do is move the wrong leg, and—presto!—

the subordinate deftly disappears. The manager is

thus left with another acquisition for his menagerie.

Of course, monkeys can be trained not to move

the wrong leg. But it is easier to prevent them from

straddling backs in the first place.

for whom. Moreover, he now sees that if he actually

accomplishes during this weekend what he came

to accomplish, his subordinates’ morale will go up

so sharply that they will each raise the limit on the

number of monkeys they will let jump from their backs

to his. In short, he now sees, with the clarity of a

revelation on a mountaintop, that the more he gets

caught up, the more he will fall behind.

Who Is Working for Whom?

He leaves the office with the speed of a person

running away from a plague. His plan? To get caught

up on something else he hasn’t had time for in years:

a weekend with his family. (This is one of the many

varieties of discretionary time.)

Let us suppose that these same four subordinates

are so thoughtful and considerate of their superior’s

time that they take pains to allow no more than three

monkeys to leap from each of their backs to his in any

one day. In a five-day week, the manager will have

picked up 60 screaming monkeys—far too many to

do anything about them individually. So he spends his

subordinate-imposed time juggling his “priorities.”

Sunday night he enjoys ten hours of sweet,

untroubled slumber, because he has clear-cut

plans for Monday. He is going to get rid of his

subordinate-imposed time. In exchange, he will get

an equal amount of discretionary time, part of which

he will spend with his

subordinates to make

Worst of all, the reason the manager sure that they learn the

cannot make any of these “next

difficult but rewarding

managerial art called

moves” is that his time is almost

Care and Feeding of

entirely eaten up by meeting his own “The

Monkeys.”

Late Friday afternoon, the

manager is in his office with

the door closed for privacy

so he can contemplate

the situation, while his

subordinates are waiting

outside to get their last

chance before the weekend

boss-imposed and system-imposed

to remind him that he will

The manager will

requirements.

have to “fish or cut bait.”

also have plenty of

Imagine what they are

discretionary time left over

saying to one another about

for

getting

control

of

the

timing

and the content not

the manager as they wait: “What a bottleneck. He just

only

of

his

boss-imposed

time

but

also of his systemcan’t make up his mind. How anyone ever got that

imposed

time.

It

may

take

months,

but compared

high up in our company without being able to make a

with the way things have been, the rewards will be

decision we’ll never know.”

enormous. His ultimate objective is to manage his

Worst of all, the reason the manager cannot make any time.

of these “next moves” is that his time is almost entirely

eaten up by meeting his own boss-imposed and

system-imposed requirements. To control those tasks,

he needs discretionary time that is in turn denied

him when he is preoccupied with all these monkeys.

The manager is caught in a vicious circle. But time is

a-wasting (an understatement). The manager calls his

secretary on the intercom and instructs her to tell his

subordinates that he won’t be able to see them until

Monday morning. At 7 pm, he drives home, intending

with firm resolve to return to the office tomorrow to get

caught up over the weekend. He returns bright and

early the next day only to see, on the nearest green

of the golf course across from his office window, a

foursome. Guess who?

That does it. He now knows who is really working

Page 14 - The Lama Review

Getting Rid of the Monkeys

The manager returns to the office Monday morning

just late enough so that his four subordinates have

collected outside his office waiting to see him about

their monkeys. He calls them in one by one. The

purpose of each interview is to take a monkey,

place it on the desk between them, and figure out

together how the next move might conceivably be

the subordinate’s. For certain monkeys, that will

take some doing. The subordinate’s next move may

be so elusive that the manager may decide—just

for now—merely to let the monkey sleep on the

subordinate’s back overnight and have him or her

return with it at an appointed time the next morning to

continue the joint quest for a more substantive move

by the subordinate. (Monkeys sleep just as soundly

overnight on subordinates’ backs as they do on

superiors’.)

As each subordinate leaves the office, the manager

is rewarded by the sight of a monkey leaving his

office on the subordinate’s back. For the next 24

hours, the subordinate will not be waiting for the

manager; instead, the manager will be waiting for the

subordinate.

Nor can the manager and the subordinate effectively

have the same initiative at the same time. The opener,

“Boss, we’ve got a problem,” implies this duality and

represents, as noted earlier, a monkey astride two

backs, which is a very bad way to start a monkey on

its career. Let us, therefore, take a few moments to

examine what we call “The Anatomy of Managerial

Initiative.”

Later, as if to remind himself that there is no law

against his engaging in a constructive exercise in

the interim, the manager strolls by the subordinate’s

office, sticks his head in the door, and cheerily asks,

“How’s it coming?” (The time consumed in doing this

is discretionary for the manager and boss imposed for

the subordinate.)

There are five degrees of initiative that the manager

can exercise in relation to the boss and to the system:

When the subordinate (with the monkey on his or her

back) and the manager meet at the appointed hour

the next day, the manager explains the ground rules

in words to this effect:

“At no time while I am helping you with this or any

other problem will your problem become my problem.

The instant your problem becomes mine, you no

longer have a problem. I cannot help a person who

hasn’t got a problem.

“When this meeting is over, the problem will leave this

office exactly the way it came in—on your back. You

may ask my help at any appointed time, and we will

make a joint determination of what the next move will

be and which of us will make it.

“In those rare instances where the next move turns

out to be mine, you and I will determine it together. I

will not make any move alone.”

The manager follows this same line of thought with

each subordinate until about 11 am, when he realizes

that he doesn’t have to close his door. His monkeys

are gone. They will return—but by appointment only.

His calendar will assure this.

Transferring the Initiative

What we have been driving at in this monkey-on-theback analogy is that managers can transfer initiative

back to their subordinates and keep it there. We have

tried to highlight a truism as obvious as it is subtle:

namely, before developing initiative in subordinates,

the manager must see to it that they have the

initiative. Once the manager takes it back, he will no

longer have it and he can kiss his discretionary time

good-bye. It will all revert to subordinate-imposed

time.

1. wait until told (lowest initiative);

2. ask what to do;

3. recommend, then take resulting action;

4. act, but advise at once;

5. and act on own, then routinely report (highest

initiative).

Clearly, the manager should be professional enough

not to indulge in initiatives 1 and 2 in relation either

to the boss or to the system. A manager who uses

initiative 1 has no control over either the timing or the

content of boss-imposed or system-imposed time and

thereby forfeits any right to complain about what he

or she is told to do or when. The manager who uses

initiative 2 has control over the timing but not over

the content. Initiatives 3, 4, and 5 leave the manager

in control of both, with the greatest amount of control

being exercised at level 5.

In relation to subordinates, the manager’s job is

twofold. First, to outlaw the use of initiatives 1 and

2, thus giving subordinates no choice but to learn

and master “Completed Staff Work.” Second, to see

that for each problem leaving his or her office there

is an agreed-upon level of initiative assigned to it, in

addition to an agreed-upon time and place for the next

manager-subordinate conference. The latter should

be duly noted on the manager’s calendar.

The Care and Feeding of Monkeys

To further clarify our analogy between the monkey

on the back and the processes of assigning and

controlling, we shall refer briefly to the manager’s

appointment schedule, which calls for five hardand-fast rules governing the “Care and Feeding

of Monkeys.” (Violation of these rules will cost

discretionary time.)

Rule 1.

Monkeys should be fed or shot. Otherwise, they will

starve to death, and the manager will waste valuable

time on postmortems or attempted resurrections.

The Lama Review - Page 15

Rule 2.

The monkey population should be kept below the

maximum number the manager has time to feed.

Subordinates will find time to work as many monkeys

as he or she finds time to feed, but no more. It

shouldn’t take more than five to 15 minutes to feed a

properly maintained monkey.

Rule 3.

Monkeys should be fed by appointment only. The

manager should not have to hunt down starving

monkeys and feed them on a catch-as-catch-can

basis.

Rule 4.

Monkeys should be fed face-to-face or by telephone,

but never by mail. (Remember—with mail, the next

move will be the manager’s.) Documentation may add

to the feeding process, but it cannot take the place of

feeding.

Rule 5.

Every monkey should have an assigned next feeding

time and degree of initiative. These may be revised

at any time by mutual consent but never allowed to

become vague or indefinite. Otherwise, the monkey

will either starve to death or wind up on the manager’s

back.

CommentaryMaking Time for Gorillas

by Stephen R. Covey

When Bill Oncken wrote this article in 1974, managers

were in a terrible bind. They were desperate for a way

to free up their time, but command and control was

the status quo. Managers felt they weren’t allowed

to empower their subordinates to make decisions.

Too dangerous. Too risky. That’s why Oncken’s

message—give the monkey back to its rightful

owner—involved a critically important paradigm shift.

Many managers working today owe him a debt of

gratitude.

It is something of an understatement, however, to

observe that much has changed since Oncken’s

radical recommendation. Command and control

as a management philosophy is all but dead, and

“empowerment” is the word of the day in most

organizations trying to thrive in global, intensely

competitive markets. But command and control

stubbornly remains a common practice. Management

thinkers and executives have discovered in the last

decade that bosses cannot just give a monkey back

to their subordinates and then merrily get on with their

Page 16 - The Lama Review

own business. Empowering subordinates is hard and

complicated work.

The reason: when you give problems back to

subordinates to solve themselves, you have to be

sure that they have both the desire and the ability to

do so. As every executive knows, that isn’t always

the case. Enter a whole new set of problems.

Empowerment often means you have to develop

people, which is initially much more time consuming

than solving the problem on your own.

Just as important, empowerment can only thrive when

the whole organization buys into it—when formal

systems and the informal culture support it. Managers

need to be rewarded for delegating decisions and

developing people. Otherwise, the degree of real

empowerment in an organization will vary according

to the beliefs and practices of individual managers.

But perhaps the most important lesson about

empowerment is that effective delegation—the

kind Oncken advocated—depends on a trusting

relationship between a manager and his subordinate.

Oncken’s message may have been ahead of

his time, but what he suggested was still a fairly

dictatorial solution. He basically told bosses, “Give

the problem back!” Today, we know that this approach

by itself is too authoritarian. To delegate effectively,

executives need to establish a running dialogue with

subordinates. They need to establish a partnership.

After all, if subordinates are afraid of failing in front

of their boss, they’ll keep coming back for help rather

than truly take initiative.

Oncken’s article also doesn’t address an aspect

of delegation that has greatly interested me during

the past two decades—that many managers are

actually eager to take on their subordinates’ monkeys.

Nearly all the managers I talk with agree that their

people are underutilized in their present jobs. But

even some of the most successful, seemingly selfassured executives have talked about how hard it is

to give up control to their subordinates.

I’ve come to attribute that eagerness for control to a

common, deep-seated belief that rewards in life are

scarce and fragile. Whether they learn it from their

family, school, or athletics, many people establish an

identity by comparing themselves with others. When

they see others gain power, information, money,

or recognition, for instance, they experience what

the psychologist Abraham Maslow called “a feeling

of deficiency”—a sense that something is being

taken from them. That makes it hard for them to be

genuinely happy about the success of others—even

of their loved ones. Oncken implies that managers

can easily give back or refuse monkeys, but many

managers may subconsciously fear that a subordinate

taking the initiative will make them appear a little less

strong and a little more vulnerable.

How, then, do managers develop the inward security,

the mentality of “abundance,” that would enable

them to relinquish control and seek the growth

and development of those around them? The work

I’ve done with numerous organizations suggests

that managers who live with integrity according to

a principle-based value system are most likely to

sustain an empowering style of leadership.

Given the times in which he wrote, it was no wonder

that Oncken’s message resonated with managers.

But it was reinforced by Oncken’s wonderful gift for

storytelling. I got to know Oncken on the speaker’s

circuit in the 1970s, and I was always impressed by

how he dramatized his ideas in colorful detail. Like

the Dilbert comic strip, Oncken had a tongue-in-cheek

style that got to the core of managers’ frustrations and

made them want to take back control of their time.

And the monkey on your back wasn’t just a metaphor

for Oncken—it was his personal symbol. I saw him

several times walking through airports with a stuffed

monkey on his shoulder.

I’m not surprised that his article is one of the two

best-selling HBR articles ever. Even with all we know

about empowerment, its vivid message is even more

important and relevant now than it was 25 years

ago. Indeed, Oncken’s insight is a basis for my own

work on time management, in which I have people

categorize their activities according to urgency and

importance. I’ve heard from executives again and

again that half or more of their time is spent on

matters that are urgent but not important. They’re

trapped in an endless cycle of dealing with other

people’s monkeys, yet they’re reluctant to help those

people take their own initiative. As a result, they’re

often too busy to spend the time they need on the real

gorillas in their organization. Oncken’s article remains

a powerful wake-up call for managers who need to

delegate effectively.

William Oncken, Jr., was chairman of the William

Oncken Corporation until his death in 1988. His

son, William Oncken III, now heads the company.

Donald L. Wass was president of the William Oncken

Company of Texas when the article first appeared.

He now heads the Dallas–Fort Worth region of

The Executive Committee (TEC), an international

organization for presidents and CEOs.

Don’t be fooled by the calendar. There are only

as many days in the year as you make use

of. One man gets only a week’s value out of a

year while another man gets a full year’s value

out of a week. - Charles Richards

The Lama Review - Page 17

Dealing with Difficult People

in a Changing World

by Terry Paulson, PhD, CSP, CPAE

Conflict is built into the very fabric of every

organization in today’s changing world. When

it is not dealt with well, it can create enemy

relationships and grow to sap the time, energy,

and productivity of even the best relationships.

Conflict can also be a catalyst that sets the

stage for needed changes. You will never deal

with conflict perfectly, but here are ten tips worth

using in dealing with your difficult people on and

off the job:

1. Talk to people instead of about

them. Dealing with conflict directly may

be uncomfortable and lead to some

disappointment, but it cuts down the

mindreading and the resentment that can occur

when problems are not dealt with directly.

Timing, tact, and taking distance will always

have their place, but make sure you still keep

conflict eyeball to eyeball.

2. We are taught from childhood to avoid

conflict and often vacillate between the pain of

dealing with unresolved problems and the guilt

Page 18 - The Lama Review

over not dealing with them. Such vacillation

saps energy and time; it can affect morale and

turnover. Be a problem solver not a problem

evader. Problem solvers avoid avoidance; they

learn to deal with conflict as soon as it even

begins to get in the way.

3. Develop a communication style that

focuses on future problem solving rather

than getting stuck in proving a conviction for

past problems. You want change, not just an

admission of guilt. Winners of arguments never

always win, because consistent losers never

forget. You want results, not enemies seeking

revenge. By focusing on future problem solving,

both can save face.

4. Problem solvers deal with issues, not

personalities. It is all too easy to abuse the

other party instead of dealing with issues. Be

assertive but affirm the rights of others to have

different positions, values and priorities. When

you personalize disagreements and attack

back, you invite escalation. Keep the focus on

mutual problem solving not name calling.

even if a few difficult people never respond.

5. Honor, surface and use resistance. Attempts at

9. If none of these suggestions work, keep your

threatening, silencing or otherwise avoiding criticism

of change will only force resistance underground and

increase the sabotaging of even necessary changes.

Explored resistance helps build clarity of focus and

action. Push for specific suggestions. If criticism is

extensive and continues even after facing it, it may

not be resistance--Know when to admit that you are

wrong.

perspective—”This too shall pass!’ Keep evidence of

your efforts to build a better relationship. Find ways

to work on projects that build new exposure in other

areas within your organization. You may just find a

new position with a different team to work with. With a

crazy or brutalizing boss or coworker, you may even

have to leave. Always invest 5% of your time in your

next career so you are continually developing career

choices. You want to stay for the right reasons, not

because you are trapped.

6. Redefine caring to include caring enough to

confront on a timely and consistent basis. Avoid labels

that give you or others excuses for not confronting a

problem—They are too sensitive or too nice, scene

makers or people who have contacts, too old or too

young, or the wrong race or gender. If you believe

people cannot change or benefit from feedback, you

will tend not to confront them. Instead, treat all equally

caring enough to be firm, fair, and consistent.

7. Avoid forming enemy relationships. The subtle

art of influence is often lost in the heat of battle.

When interaction becomes strained or bias exists, the

negative interaction coupled with the distance that

often results invites selective scanning and projection.

We see what we want to see to keep our enemies the

enemy.

If a relationship is limited to polite indifference and

significant negative interaction, expect polarization

and an enemy relationship. In such relationships

everyone loses. Take seriously the words of

Confucius, “Before you embark on a journey of

revenge, dig two graves.” Even your most difficult

person usually has some people they work with

well. Make one of those people you. Don’t look for

the worst; learn to look for the best in even difficult

people.

10.

Finally, don’t forget to spend some time

looking in a mirror. Ron Zemke put it well when he

said, ‘If you find that everywhere you go you’re always

surrounded by jerks and you’re constantly being

forced to strike back at them or correct their behavior,

guess what? You’re a jerk.” As with all of life, start by

making sure that you are not being difficult yourself.

BYLINE INFORMATION

Dr. Terry Paulson is author of The Dinner, 50 Tips for

Speaking Like a Pro and They Shoot Managers Don’t

They? As a speaker, he helps leaders and teams

make change work. For more information visit http://

www.terrypaulson.com or contact directly at (818)

991-5110 or terry@terrypaulson.com

Never let yesterday use up today.

Richard H. Nelson

8. Invest time building positive bridges to your

difficult people. Abraham Lincoln reportedly said, “I

don’t like that man. I’m going to have to get to know

him better.’ Don’t be insincere; look for ways to be

sincere. It takes a history of positive contact to build

trust. Try building a four-to-one positive to negative

contact history. Give specific recognition and ask for

assistance in the areas you respect their opinions.

Work together on an common cause and search for

areas of common ground. Even if bridge building

doesn’t work, by being a positive bridge builder, you

build a reputation all will see and come to respect

The Lama Review - Page 19

Copyright 2008 by Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. For reprints, call HBS Publishing at (800) 545-7685.

BH 272

Time bandits: How they are created, why they are tolerated, and

what can be done about them

Time Bandits

a,

a

David J. Ketchen, Jr. , Christopher W. Craighead , M. Ronald Buckley

b

b

Auburn University, Lowder Business Building, Auburn, AL 36849, USA University of Oklahoma, 307 West Brooks, Norman,

OK 73072, USA

KEYWORDS

Time bandits; Resource utilization; Reward

systems; Job design

Abstract

Organizations today own little slack, and they

must very carefully manage their resources.

In this article, we describe an omnipresent,

yet often ignored resource utilization problem whereby some workers abandon certain

responsibilities and use the freed-up time

to pursue personal interests such as hobbies and side businesses. In essence, these

“time bandits” work part-time in exchange

for full-time pay. While bandits are a minority among workers, their negative effects

are significant and widespread. Specifically,

banditry undermines an organization’s mission, morale, and productivity, as well as

putting stakeholder support at risk. In an effort

to address this problem, we offer insights in

three areas. First, we identify key causes of

banditry, including supervisors not enforcing

performance standards, poorly constructed

reward systems, and the failure to recognize

individual differences when designing jobs.

Second, we describe reasons why banditry is

tolerated within organizations, such as supervisors’ desire to avoid conflict and their fear of

being labeled as hypocrites. Most importantly,

we offer a set of techniques that can prevent

and reverse banditry. These include carefully

defining expectations, intervening quickly

when the symptoms of banditry appear, reducing bandits’ compensation over time, and

designing jobs that capitalize on individuals’

varied skills and motivation. © 2007 Kelley

School of Business, Indiana University. All

rights reserved

1. A thief by any other name…

“Sam Cooper” (a pseudonym) is a mid-level

manager within a division of a Fortune 500

firm. The firm’s business centers on serving large, competitively-bid contracts. These

contracts apply to fixed periods of time, so a

steady flow of new contracts is needed for the

firm to remain successful. Sam’ performance

in servicing existing contracts is regarded as

reasonable. A much different situation arises

where preparing bids for new contracts is

concerned. At strategy meetings, Sam contributes both enthusiasm and insight about

how to win each competition. When it comes

time to actually write a proposal for a new

contract, however, Sam is always “too busy”

or “traveling too much” to participate. Yet, as

an avid surfer, Sam always seems to have

plenty of time throughout the week to hit the

beach.

“Barb Dobler” is a department head within a

state government agency devoted to public

health. Barb possesses adequate technical

Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: ketchda@auburn.edu (D.J. Ketchen, Jr.), craigcw@auburn.edu

(C.W. Craighead), mbuckley@ou.edu (M.R. Buckley).

0007-6813/$ -see front matter © 2007 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2007.11.005

Page 20 - The Lama Review

skills and her performance on this portion of her

job is satisfactory. However, her main responsibility

is managing others, a role that she eschews. Barb

not only fails to give subordinates guidance and

support, she also verbally abuses them. Ignoring her

managerial duties has freed up a lot of time for Barb,

and she uses this time to trade stocks online. Upper

management has sent Barb to a series of out-of-town

seminars on effective management, but she has

treated these trips as vacations.

“Phil Moultor” has long served as a professor at a

large public university. Like most professors at such

institutions, Phil is assigned responsibilities in teaching and research. In the 1980s, Phil’s record of research accomplishments resulted in his appointment

to a position that granted a reduced teaching load.

The university’s expectation was that Phil’s research

activity would flourish via the freed-up

time. In the intervening decades, however,

Phil has conducted very little research.

He teaches his classes – atask that takes

only a few hours a week, given his reduced

teaching load – and contributes little else to

the university. Meanwhile, Phil works many

hours at the Italian restaurant that he runs

“on the side.”

contention, based on a collective total of 44 years

at seven universities, is that banditry is a pervasive

problem within educational institutions. In particular,

we have observed the widespread existence of

bandit professors such as Phil Moultor, who have

made a conscious decision to not fulfill the research

responsibilities of their positions. At many business

schools, the work assignment of a tenure track

professor includes a significant portion of their

time (perhaps 25% to 50%) that is supposed to be

allocated to research activities. Often, bandits will

teach their classes but that is the extent of their

contribution to the institution. Bandit professors are

generally tenured, and they treat tenure not as the

intended protector of academic freedom, but as a

sinecure and a license to steal from the educational

system. Hambrick (2005, p. 300) has stated that

abandoning research responsibilities is a main reason

Several forms of theft take place within

organizations. Some are well known,

such as insider trading, shrinkage (where

employees pilfer goods), and embezzlement.

The anecdotes offered above illustrate

another form of theft, one that most of us

are aware of intuitively but that has not

yet been discussed in the practitioner or

academic literatures. In each case, a person

has chosen to not fulfill part of his or her

assigned work responsibilities. We label

these people as “time bandits” because they

are stealing time from their employers and

therefore are paid for full-time employment,

but only work part-time. With the time freed

up by shirking some of their responsibilities,

bandits pursue hobbies (such as surfing or

online stock trading), enjoy leisure time (such

as following the latest celebrity gossip via the

Internet), or enrich themselves through side

businesses (such as running a restaurant or

a real estate agency).

Most of our direct experience with time

bandits (or, more simply, “bandits”) comes

through our roles as professors. Our

The Lama Review - Page 21

why “if tenure could be redecided five years after the

initial decision… about 20% to 25% of professors

would be asked…to pack their bags.”

While tenure clearly facilitates banditry among some

professors, the cases of Sam Cooper, Barb Dobler,

and many others demonstrate that the absence of a

tenure system has not prevented banditry from arising

within businesses and government organizations.

Indeed, we routinely hear MBA students, College of

Business Advisory Board members, our spouses,

and our friends offer complaints, jokes, and derisive

comments about the proliferation of bandits at their

places of employment. While bandits are a minority,

it appears that they can be found within the corral of

most every organization.

Business executives may be dismayed to learn

that our expectation is that banditry will become

more prevalent within industry over time. Organizations may be most susceptible to banditry when an

employee has the ability to be frequently out of the

office. Salespeople and professors, for example, often

have the freedom to come and go as they please.

This situation allows potential bandits to claim to be

“working at home” or “on a business trip” while they

are engaged in hobbies or side businesses or just

avoiding work. More broadly, businesses increasingly

rely on arrangements such as virtual teams and

telecommuting whereby workers receive little direct

supervision and can adjust the hours they work

(Ford & McLaughlin, 1995; Greenberg, Greenberg,

& Antonucci, 2007). Like the bandit salesperson or

professor, some workers will not resist the opportunity

to misuse this freedom. Thus, part of our message

to executives is to take note of the abuses that have

evolved among a minority of employees and strive

to prevent similar scenarios from developing in

your organizations. In this sense, we believe that a

daunting challenge sales managers and university

administrators have faced for decades foreshadows

an emerging dilemma for many supervisors.

We do not believe that all bandits maliciously

pursue the theft of time. Some employees become

bandits due to their situational context: as a result

of boredom, lack of direction, lack of support, or

frustration with work. Regardless of the underlying

causes, banditry is costly. Indeed, the dollar value of

banditry is substantial. For the purpose of illustration,

consider that according to the Association to Advance

Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, 2006),

the average salary of a business school professor

is $96,000. If we assume a fringe benefit factor of

Page 22 - The Lama Review

25%, this equates to $120,000 in direct and indirect

compensation. A professor with a time allocation

for research of 40% (a percentage that varies by

appointment and school) is compensated $48,000

annually for his or her research efforts. Bandits such

as Phil Moultor, who are disengaged from research,

are stealing this amount of money every year from

university stakeholders. Similar calculations can be

made for industry and government desperados such

as Sam Cooper and Barb Dobler.

This reality becomes more troubling when the

sources of the money with which bandits abscond

are considered. Faculty salaries are derived from

state funds, tuition dollars, and endowments from

the donations of alumni, companies, and friends of

the university. Essentially, bandit professors rob their

colleagues, their institutions, and university stakeholders (such as students and legislatures) as surely

as if they stuck a pistol in their stakeholders’ ribs.

Within industry, bandits rob firms’ shareholders and

fellow employees, among others. Within government,

taxpayers are the primary victim of banditry. However,

the ill effects of bandits go well beyond the dollars

pilfered; we take a closer look in the next section.

2. The effects of banditry

2.1. Undermining the mission

All organizations have missions that need to be

accomplished and some fixed amount of resources

at their disposal to achieve those missions. The loss

of resources through banditry undermines organizations’ ability to meet the challenges of their missions.

For example, as noted above, Barb Dobler is a

department head within a state agency devoted

to public health. The mission of this agency is “to

promote and protect the health and safety of all”

citizens of the state. By neglecting the managerial

aspect of her position, Barb has undermined the

ability of subordinates to work toward this goal. Every

hour that subordinates spend confused about their

duties or spend protesting Barb’s abuse to higher

administrators is an hour that could have been

devoted to improving the health and safety of the

state citizenry. The mission of Sam Cooper’s firm

centers on helping customers achieve success. Sam’s

stealthy refusal to work on the contract proposals that

create new customers jeopardizes the firm’s future

by hurting its ability to serve its constituents and

accomplish its mission.

For most business schools, teaching and research

are the two main elements of their missions. Deans

today face the unenviable task of leading their

schools to make contributions to these elements in

a complex and challenging context. According to the

AACSB (2002, p. 2), “the most critical problem facing

business schools today is the insufficient number of

new PhDs being produced worldwide.” There is little

slack left and this supply shortage could drastically

reduce the ability to meet teaching and research

obligations. The AACSB (2003, p.1) predicts that

“unless decisive action is taken to reverse declines

in business doctoral education, academic business

schools, universities, and society will be faced with an

inevitable erosion in the quality of business education

and research.” To cover classes, many schools are

moving to a faculty structure whereby appointments

are tilted more heavily toward part-time instructors

rather than traditional tenure-track slots (Nemetz &

Cameron, 2006). As a result, fewer faculty members

are tasked with serving a critical component of the

mission of the university; that is, research. The effects

of banditry are thereby spread out over a smaller

number of research faculty and its effects become

more damaging and noticeable (see Albanese & Van

Fleet, 1985).

subordinates in a position to succeed. If these subordinates failed, the result would be that none of

the agencies’ missions would be effectively served.

Because Barb’s agency received funding from these

allies, the difficulties Barb created ultimately reduced

the resources of her agency.

Key university stakeholders oftentimes possess

only a peripheral understanding of the nature of

the work done by professors (Gordon, 1986). For

example, legend has it that a university president was

once summoned to a state legislative hearing. The

following exchange ensued:

Lawmaker: “How many hours do your professors

typically teach?”

University president: “Six hours.” (Meaning per week)

2.2. Undermining morale and productivity

Our observation over time has been that bandits

have significant deleterious effects on the work

habits of other employees. Particularly strong-willed

and dedicated workers have the focus needed to

concentrate on their own tasks. However, most of

us ‘mortals’ take notice of and are influenced by the

situation around us. A ‘law abiding’ equity sensitive

worker who observes bandits getting away with

working part-time may question the wisdom of

working hard. Equity theory would suggest that such

people will reduce their efforts until they believe that

they are receiving rewards relative to their inputs

at a similar rate to the bandits in their department

(Adams, 1965). The result is that, like rabbits, bandits

multiply. Another outcome predicted by equity theory

is that productive workers who observe banditry find

it intolerable, become cynical, and ultimately leave

in order to join an organization with more distributive

justice (McFarlin & Sweeney, 1992). Furthermore,

an emotional contagion (Hatfield, Cacioppo, &

Rapson, 1994) may occur whereby other employees

start to tthink and feel like the bandit. None of these

possibilities bode well for an organization

.

2.3. Undermining institutional support

No business, government agency, or university can

“go it alone.” Instead, each organization depends

on the support and resources of other organizations

in order to function. Through their behavior, bandits

create questions about whether their organizations

are good investments and thereby jeopardize their

support. For example, Barb Dobler’s agency works

in conjunction with other state agencies that have

similar missions, such as protecting the environment.

Over time, Barb’s managerial malfeasance made

these other agencies reluctant to work with her.

They had little confidence that Barb would put her

Lawmaker: “What do they do the other two hours of

the day?”

The mystery surrounding what we do has helped