Rethinking Revenue Recognition - Fakultät für Betriebswirtschaft

Munich Business Research

Münchner Betriebswirtschaftliche Beiträge

Rethinking Revenue Recognition

– Critical Perspectives on the IASB’s Current Proposals –

Michael Dobler & Silvia Hettich

# 2006-03

First Draft: December 2005

Rethinking Revenue Recognition

– Critical Perspectives on the IASB’s Current Proposals –

Michael Dobler * and Silvia Hettich **

Abstract:

Acknowledging deficiencies in current regulations and aiming at convergence, the

IASB is conducting a joint project with the FASB to develop a principle-based standard on revenue recognition. The tentative proposals feature an asset-liability approach relying on measurement at fair values or at allocated consideration amounts. Based on conceptual, analytical, and empirical evidence, this paper finds that the current proposals conflict with (i) qualitative characteristics of information, (ii) objectives of financial reporting, and (iii) current and emerging regulatory framework. Main results show that the fair value approach yields more severe conflicts than the allocated consideration amount approach. The proposals ambivalently prefer relevance over reliability and can give rise to adverse incentives for investment decisions and earnings management. While both approaches comprise inconsistencies with existing

IASB/IASCF regulations and developments in other projects of the IASB, our results particularly question whether the current proposals meet the endorsement criteria of Art.

3(2) of Regulation (EC) 1606/2002.

Keywords: Decision Usefulness; IFRSs; Income Concept; Revenue Recognition;

Stewardship.

JEL-Classification:

K22; M41.

* Dr. Michael Dobler, MBR, Chair for Accounting and Auditing, Ludwig-Maximilians-University

Munich, Ludwigstr. 28/RG IV, D-80539 Munich, Germany; e-mail: dobler@bwl.uni-muenchen.de.

** Dipl.-Kffr. Silvia Hettich, MBA, MBR, Chair for Accounting and Auditing, Ludwig-Maximilians-

University Munich, Ludwigstr. 28/RG IV, D-80539 Munich, Germany; e-mail: hettich@bwl.unimuenchen.de.

1

1 Introduction

IFRSs are known to lack a well-founded concept of income (Haller and Schloßgangl,

2005; Hettich, 2006). Particularly, regulations on revenue recognition show inconsistencies, e.g., between IAS 18 and the Framework, and loopholes, e.g., concerning multi-element arrangements (IASB, 2005e; Wüstemann and Kierzek, 2005).

Under US-GAAP, revenue recognition is addressed by almost 200 references which are not fully consistent. Particularly, given recent accounting scandals in the USA, revenue recognition is considered to be the most urgent topic to be dealt with by the FASB

(FASAC, 2005b; FASB, 2005b; GAO, 2002).

Given (i) deficiencies in both IFRSs and US-GAAP and (ii) the aim of convergence, the

IASB and the FASB have been rethinking revenue recognition in a joint project since

2002. Aiming at a general and comprehensive standard, the project

Revenue

Recognition

develops a conceptual revenue recognition model largely independent from existing standards. The tentative proposals feature a valuation-based asset-liability approach measuring liabilities arising from enforceable performance obligations at their fair value or at an allocated consideration amount (FASB, 2005a; 2005b; IASB, 2005b,

2005c, 2005e; 2005h, 2005i). While all decisions and proposals made to date are tentative and a discussion paper is scheduled for the second half of 2006, the proposals take shape and imply far reaching changes in revenue recognition compared to current

IFRSs particularly relevant for IFRSs-users in the EU (Ernstberger, 2005; Wüstemann and Kierzek, 2005; Dobler, 2006).

This paper is among the first to investigate the proposals of the project

Revenue

Recognition

, thereby considering developments up to December 2005. Unlike other papers which discuss accounting differences between the proposals and current IFRSs, i.e., IAS 11 and IAS 18, we aim at evaluating the proposals from overriding perspectives based on conceptual, analytical, and empirical findings. Particularly, we take (i) an informational perspective referring to qualitative characteristics of financial information, (ii) an objectives-based perspective linked to decision-usefulness and stewardship purposes of financial reporting, and (iii) a regulative perspective considering compatibility with recent and emerging regulations.

2

Main results cast doubt on the reliability and the relevance of the proposed concepts particularly concerning initial and subsequent measurement of performance obligations.

Recognising revenue and expense with reference to (hypothetical) market prices (in the fair value approach) or with reference to (modified) estimated sales prices (in the allocated consideration amount approach) incorporates managerial judgement and can provide a misleading indicator for future performance. Specifically, when applying the fair value approach, a loss can occur at contract inception although performing the contract is expected to yield profit and vice versa. While challenging decision usefulness, we argue that the fair value approach provokes accounting and real earnings management, yields adverse incentives for investment decisions and is inappropriate for stewardship purposes. These concerns are partially mitigated in the allocated consideration amount approach. Based on the findings we detect incompatibilities with both current IASB/IASCF regulations and developments in other projects conducted by the IASB. We conclude that the current proposals of the project

Revenue Recognition

do not comply with EU endorsement requirements set out in Art. 3(2) of Regulation

1606/2002 which is likely to impact the further proceeding of the project.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. The next section surveys research background. Section 3 presents the current proposals of the project Revenue

Recognition

, which we discuss in Section 4. Section 5 concludes.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1

Conceptual Findings

Financial statements are (i) to provide information for decision making purposes (F.12) and (ii) to show the results of stewardship of the management (F.14). Both objectives can not be achieved by using the same set of standards (Gjesdal, 1981). Likewise, not all concepts of income do equally fit to deliver the information necessary (Baetge, 1970:

23).

Decision usefulness requires relevance and reliability of information (Barth, Beaver, and Landsman, 2001: 80). The concept of economic income defines income as the increase in wealth (Smith, 1890). Fisher (1906) and Lindahl (1919) show that under certain conditions income equals the interest on wealth at the beginning of the period.

3

For an entity, wealth is derived by discounting future cash flows (Solomons, 1961).

Economic income is ideal for decision making purposes since future developments are considered and changes therein are recognised immediately (Franke and Hax, 2004).

But when lifting the condition of a perfect capital market, economic income is no longer well-defined. The necessary assumptions about the future undermine the reliability of the income figure. The manager can influence income without detection by investors because the figure can neither be verified nor falsified. An auditor is only able to check for plausibility (Dobler, 2004).

Accounting profit results from the difference between realised income and expense which follow from transactions and events in the corresponding period (Belkaoui,

2000). Assets and liabilities are carried at historical cost until they are used up or sold; revenues and expenses are matched (revenue-expense approach) (Paton and Littleton,

1955). For decision making purposes, accounting income delivers reliable information.

As it results from past transactions and events and is well documented, it can relatively easily be verified. As accounting profit anticipates future losses but not future gains

(i.e., conservative accounting), the income figure is biased. Nevertheless, assets and liabilities carried at historical cost can be interpreted as a set of resources generating future profit and can, thus, serve as an indicator for users (Leuz, 1998).

While the revenue-expense approach focuses on the recognition criteria for income and expenses to compute profit, the asset-liability approach defines profit as changes in values of assets and liabilities. These values can be historical values, current or market values, values in use or other. Accounting profit uses historical costs for assets and liabilities, whereas the current value concept of income uses current values.

market values are not well-defined because they can either be entry or exit values. If market prices don’t exist, the values have to be estimated. The profit consists of a realised and an unrealised component (Edwards and Bell, 1961). The change in value constitutes relevant information for users and impedes a biased income figure. Market values can be interpreted as the best estimate of future prices so that decision relevant information is displayed. But like the economic concept of income, the current value

1 While acknowledging that the revenue-expense approach can be understood as an asset-liability approach carrying assets and liabilities at historical cost, for the rest of the paper, we refer to the asset-liability approach for any other measurement basis.

4 concept of income is not as objective as the accounting profit and, therefore, undermines reliability.

The stewardship function of financial statements implies that investors have the right to get information about the use of their invested capital. Thus, information about the current position of a company is needed in order to assess the investment. In consequence the objectives of stewardship and decision usefulness overlap. But as accounting standards influence the decisions of managers (Moxter, 1962; Birnberg,

1980; Hunt, 1995), standards also have to be evaluated upon the incentives induced on managers. Further assuming that the manager’s compensation is partly based on the

is reliable at the same time.

Economic income induces the manager to take favourable decisions for the company since the corresponding profit is recognised immediately and he, thus, benefits from the investment decision instantaneously (Laux, 1995). But the manager can influence the income figure since assumptions about the cash flows from investments and the interest rate for discounting the cash flows have to be made (Leffson, 1966). Thus, the investor will not want to use economic income. Accounting profit is less inclined to be managed by the manager and seems appropriate for stewardship purposes (Leffson, 1966; Ijiri,

1970). Since profit is not anticipated, the manager is not rewarded for the investment decision until cash flows are realised. He may, hence, not have the incentive to invest in favourable projects (Jensen and Smith, 1985). Current value concept of income, just like the economic concept of income, rewards the manager for investment decisions taken immediately since market values are used to compute profit. But the income figure is not necessarily reliable (Ballwieser, Küting, and Schildbach, 2004). As the investor is not able to detect deviations from “real profit” because the manager influences income upwards, the manager is compensated by anticipated profit. This does not induce the manager to take decisions favourable for the investor or the entity, because the delivered

3

2 Accounting-based compensation can be used to mitigate agency problems. For a discussion see

Holmström and Milgrom (1987); Kuhn (1966: 565); Antle and Smith (1985); Jensen and Murphy

(1990); Sloan (1993).

The income figure should increase when the performance of the entity increases and vice versa.

Thus, when a manager performs well and the performance of the entity increases he should benefit from the increase.

5 benefits are not shown. Conservative accounting, thus, impedes to reward the manager for anticipated profit but rather compensates for delivered performance (Dutta and

Zhang, 2002).

2.2

Analytical Findings

In analytical principal-agents-models, Gjesdal (1981), Antle and Demski (1989),

Christensen and Demski (2003), and Wagenhofer and Ewert (2003) find that revenue recognition or accounting systems in general that are best for valuation purposes are not necessarily appropriate for stewardship purposes. However, they do not discuss any specific accounting rules like fair value accounting or conservative accounting.

When discussing decision usefulness, considerations about the trade-off between relevance and reliability are focussed on. But, information cannot be relevant without being reliable to a certain degree. Kirschenheiter (1997) interprets reliability of accounting information as the precision of a signal and relevance as the covariance of the signal and the asset’s “true” value. If the manager is only able to report the higher

(lower) of the two estimates, the market incorporates this information and adjusts market price down (up) which reflects the incorporation of the bad (good) news of the other signal (assuming it provides relatively more information about the true value of the asset). Dye and Sridhar (2004) assume that the report of an accountant consists of information solely known by the manager and other information observable by the accountant. By placing more weight on the manager’s information to include more useful information in the report, incentives for a manager are created to manipulate the report. Anticipating this behaviour, capital market participants price the firm accordingly. Aggregation of information tempers the manager’s incentives and is in a broad range of circumstances superior to disaggregated information. In contrast to the efficient market hypothesis (e.g., Bernard and Shipper, 1994), Barth, Clinch, and

Shibano (2003) show that recognition versus disclosure has different effects on the

(market) price informativeness, which depends on the recognised amount, the disclosed information, share price and expertise acquisition. Separate recognition always increases price informativeness compared to disclosure regimes. Considering aggregate information with and without disclosure, results are more complex. Surprisingly, under

6 certain conditions, the recognition of a highly unreliable (reliable) amount can result in greater (lower) price informativeness.

For stewardship purposes, agency models that govern more than one period show different results.

4 Liang (2000) examines two sources of information. One is the

accounting report, the other the self-report of the manager who communicates private, unverified information. As the accounting report serves as control of the self report, later revenue recognition is optimal. Wagenhofer (1996) and Kwon (2004) suggest conservative accounting as superior since it motivates the manager to increase effort and, thus as assumed, market value. Dutta and Zhang (2002) and Baldenius and

Reichelstein (2000) identify conservative accounting as superior to fair value accounting when storage is taken into consideration. As goods become obsolete, a lower of cost or market rule is appropriate to create incentives for managers. Kwon, Newman, and Suh (2001) find that the principal always elects conservative accounting rules when the agent can only be punished to a certain extent. Another stream of models compares fair value accounting and cash accounting. Kwon (1989), Rogerson (1997), Dutta and

Reichelstein (1999) and Reichelstein (2000) conclude that accrual accounting is preferable compared to cash accounting. As the models lack a comparison between conservative and fair value accounting, they are limited in scope. This implies that for stewardship purposes accrual accounting is necessary and conservative accounting for computing residual income appears favourable.

2.3

Empirical Findings

For decision making purposes, fair values are often assumed to be relevant compared to historical cost. While conceptual and empirical results are mixed, value relevance of fair values might be found empirically. Barth (1994) investigates the incremental information content of fair values of investment securities and the related gains and losses and finds that the disclosure of fair values does have information content besides historical cost, while the corresponding gains and losses do not. Ahmed and Takeda

(1995) show a significant association between changes in fair values and share price.

Barth, Beaver, and Landsman (1996) and Eccher, Ramesh, and Thiasgarajan (1996)

4 The following discussion is based on the result that residual income is a superior measure for compensation purposes. Residual income can be computed by using fair value or conservative accounting. Thus, accounting plays an important role in determining residual income.

7 ascertain a significant association between fair values and market value but only for loans, securities, and long-term debt respectively investment securities. Nelson (1996),

Ventkatachalam

(1996), Park, Park, and Ro (1999), Simko (1999), and Graham, Lefanowicz, and Petroni

(2003) obtain similar results especially for securities that are traded on an active market.

In contrast, Petroni and Wahlen (1995), Wampler and Posey (1996), and Khurana and

Kim (2003) don’t find a significant association between the fair values of certain financial assets and the market value. Likewise, not all of the studies identify fair values as value relevant in every instance. The studies mainly focus on financial instruments since fair values of other kind of assets or liabilities are often not available. A general conclusion about the predominance of fair values concerning decision usefulness is, hence, not possible.

Empirical evidence concerning the stewardship function of the income figure shows that the behaviour of managers can be influenced if they participate in income. Clinch and

Magliolo (1993) and Natarajan (1996) find a significant association between compensation of a manager and the operating profit as well as profit and working capital. Several studies conclude that permanent earnings play a major role in CEO compensation (Baber, Kang, and Kumar, 1998, 1999; Gaver and Gaver, 1999; Ashley and Yang, 2004). Permanent earnings which can be interpreted as an approximation of economic income are future-oriented and create as part of the manager’s compensation incentives for long-term decision taking. The empirical results are controversial to the analytical results. One reason might be that the income figure is not considered as sufficient for the compensation of the manager since – as the shareholder value approach suggests – the manager should increase market value of the entity which is not only influenced by income but by other factors as well. This conclusion is consistent with empirical evidence that finds a declining usage of the income figure for management compensation in the past years (Bushman et al., 1998; for an overview

Bushman and Smith, 2001).

5 Therefore, a combination of income and share prices is often used (Dechow and Sloan, 1991). Only few analytical models examine the combination of the two measures (e.g., Dutta and Reichelstein,

2005; Christensen, Feltham, and Ş abac, 2005).

8

3 Current Proposals of the Project Revenue Recognition

3.1

Motivation

Since 2002 the IASB and the FASB have been conducting the joint project

Revenue

Recognition

. For years, revenue recognition has been assessed a main area to be addressed by standard-setters. Acknowledging weaknesses in current regulations, which are criticised as a major factor for recent accounting scandals (GAO, 2002), both boards are rethinking revenue recognition on a conceptual basis and largely independent from current standards. Conceptual models are tested in exemplary arrangements to assess their adequacy and the need for amendment or for further guidance. Particularly, the boards aim at a general and comprehensive accounting standard on revenue recognition.

While this standard shall replace the existing standards IAS 11 and IAS 18, certain industries or transactions might be excluded from its scope. There are two main objectives aimed at by the IASB and the FASB (FASB, 2005b; IASB, 2005e):

(1) Shortcomings in current concepts and standards shall be eliminated.

(2) Convergence of requirements by the IFRSs and in the United States shall be promoted.

Concerning the first objective, the FASB has to reconcile nearly 200 revenue recognition requirements identified in US-GAAP (FASB, 2005b). The IASB highlights that current IAS 18 relies too much on the occurance of critical events, does not provide guidance on multi-element contracts, and does not accord to the frameworks definitions

(IASB, 2003b, 2005e). However, there are further deficiencies within the Framework, e.g., concerning the unclear distinction of revenues and gains (F.74-77) and the reluctant definition of profit (F.69, .105) as well as inconsistencies (i) between the framework and standards, (ii) between IFRSs and (iii) within single IFRSs (Hettich, 2006). Overall, the Framework and the IFRSs are not based on a well-founded concept of income, mixing essentials of an asset-liability approach and a revenue-expense approach as well as the recognition of revenue and gains (as well as expenses) in profit or loss or in equity (with and without recycling) (Haller and Schloßgangl, 2005; Hettich, 2006). The project Revenue Recognition will not address all of these issues.

9

Concerning the second objective, the boards aim at convergence. The FASB subsumes convergence under “improving quality of financial reporting in the United States”

(FASB, 2005b). Despite sharing resources and co-ordinating activities, both boards independently deliberate and decide on the project’s issues. Differences in decisions taken by the boards undermine convergence and suggest that political pressure can influence the votes of the boards.

3.2

Recognition

When starting to conduct the joint project on revenue recognition, the IASB and the

FASB decided to follow an asset-liability approach instead of a revenue-expense approach (FASB, 2002; IASB, 2002). The boards assume that a revenue-expense approach yields severe problems with defining earnings processes and is too difficult to be followed. Rather they aim at recognising revenue on the basis of changes in assets and liabilities arising from contracts with customers, but without considering supplemental realisation or earnings criteria (FASB, 2005b; FASB and IASB, 2005;

IASB, 2005a, 2005e).

According to the proposed model, enforceable contracts with customers can give rise to assets and liabilities. A contract is a set of explicit or implicit promises which a court will enforce. Large penalties for a breach of a contract and prepayment can indicate enforceability. Contract inception shall be determined according to general customary business practice and the entity’s specific conduct. While contractual rights need not be worthy of enforcement, i.e., costs of enforcement equal or exceed its benefits for the potential plaintiff, rights or obligations shall be unconditional or mature to give rise to assets or liabilities (IASB, 2004e, 2004f, 2004g, 2004h). The probability of future inflows or outflows of resources embodying economic benefits shall not impact recognition, but will affect measurement (FASB, 2004a; IASB, 2003a, 2005e).

The IASB agreed on the rebuttable presumption that the unit of account is a whole contract if the subjects of a wholly or partially executory contract are fungible and the legal remedy for a breach is money. But if the subjects are unique and legal remedy is specific performance, the unit of account shall be the assets and liabilities arising

10

6 Performance obligations are tentatively defined as legally enforceable

obligation of a reporting entity to its customer, under which the entity is obligated to provide goods, services, or other rights. Performance obligations shall be separated from the customer’s point of view, i.e., based on whether the performance has identifiable utility to the customer. Utility to the customer shall be assumed if the goods, services, or other rights underlying the performance obligation can either be resold separately by the customer (in a market still to be specified) or be sold separately or as an optional extra by another vendor. Moreover, any unconditional stand ready obligation is considered to have utility to the customer and shall be a separate unit of account (IASB, 2005c, 2005h, 2005i).

There are two perspectives still discussed to define revenue more precisely, which mainly differ when third parties perform (FASB, 2003; IASB, 2003c, 2003e, 2004a;

Ernstberger, 2005):

(1) Revenues are increases in the reporting entity’s assets or decreases in its liabilities resulting from activities which are integral to the provision of goods, services, or other rights ultimately destined for customers by the entity itself ( broad performance view ).

(2) Revenues are decreases in the reporting entity’s liabilities resulting from the extinguishment of performance obligations irrespective of whether the entity itself or third parties perform on behalf of the entity ( liability extinguishment view

).

The latter view seems to be preferred given that the IASB tentatively decided that

“performance by third parties of the entity’s obligations ... unless those third parties legally assume those obligations.” (IASB, 2004f: 15) The IASB acknowledges that income shall be defined before revenue can be defined and that the distinction between revenues and gains shall be sharpened (IASB, 2004h).

6 This corresponds with distinguishing contractual obligations settled by financial or non-financial items in the course financial instruments (IAS 32.8, 39.5).

11

3.3

Measurement

While assets arising from contractual rights shall be measured at their fair value considering credit risk and the value of money if material (IASB, 2004b), there is controversy on the measurement of performance obligations. Until mid-2005, the project relied on the fair value. Due to diverging notions and problems of the measurement approach, the IASB and the FASB now explore an alternative measurement basis, which allocates the total consideration among the performance obligations based on estimated sales prices in general. Thus, two – potentially mixed – measurement bases for performance obligations are discussed (FASB, 2005b; IASB,

2005e):

(1) fair value; and

(2) allocated consideration amount.

The fair value is defined as the amount for which a liability could be settled, or an asset exchanged, between knowledgeable, willing parties in an arm’s length transaction (e.g.,

IAS 18.7, 32.11, IFRS 5.Appendix A). The project refers to the fair value as a legal layoff amount, i.e., the amount which the reporting entity would have to pay to transfer the performance obligation to another entity in a business-to-business market (IASB,

2005a). The boards discussed to measure the fair value based on (i) actual transactions of the reporting entity; (ii) actual transactions of other entities, e.g. competitors; (iii) proposed transactions; or (iv) hypothetical transactions between entities (IASB, 2004i).

Basically, the boards agreed on referring to the FASB’s fair value hierarchy, which estimates fair value based on (FASB, 2004b; IASB, 2004c, 2004f)

(1) quoted prices for identical items on active markets;

(2) quoted prices of similar items on active markets, if (1) is not possible; or

(3) valuation models incorporating significant entity-specific inputs, if (1) and (2) are not possible.

Given that an active market requires (i) homogenous items traded; (ii) willing buyers and sellers at any time; and (iii) prices available to the public (IAS 36.6, 38.8), strictly applying the hierarchy means measuring fair values on level (3) in many cases.

Applying the hierarchy less strictly can incorporate hypothetical prices charged by other

12 vendors and gives rise to problems in determining the relevant market or relevant vendor.

As a major feature of the fair value approach

revenue (or expense) has to be recognised at the inception date if the consideration amount does not equal the aggregate of fair values of the performance obligations arising from an enforceable contract at contract inception (IASB, 2003d). If changes in the subsequent measurement are neglected, the extinguishment of performance obligations will determine subsequent revenue recognition. However, the boards proposed, but did not decide on remeasuring contractual assets and, more importantly, contractual liabilities at their fair value (IASB,

2003a, 2005g). This gives rise to potential volatility in measurement, earnings and accounting ratios which are not directly linked to (physical) liability extinguishment.

The boards also considered to measure the fair value of performance obligations based on the customer consideration amount, i.e., the amount of consideration paid or to be paid by the customer (IASB, 2004d, 2004i). This aims at a business-to-customer market, but measuring obligations based on customer consideration can be conceptually inconsistent with the measurement objective of fair value. Although the IASB favours the fair value approach, the boards agreed to explore the latter approach preferred by

FASB when reviewing the project strategy in mid-2005 (IASB, 2005b, 2005c, 2005g).

This alternative approach

aims at measuring performance obligations at the allocated consideration amount

7 This amount is determined two-fold. It is the aggregate of the (i)

estimated sales price of good, service, or other right, and (ii) the pro rata portion of the residual between the customer consideration amount and the sum of estimated sales prices of the performance obligations based on the relative sales price of that performance obligation (IASB 2005c, 2005i).

The first component shall reflect estimated average sales price. This is the price at which a good, service, or other right is sold or is capable of being sold on a stand-alone bases or as an optional extra. It shall be measured according to the following hierarchy based on (IASB, 2005b, 2005h, 2005i)

7 Previously, the project referred to the terms “performance value” (IASB, 2005g) and “customerbased value” (IASB, 2005h) instead of allocated (customer) consideration amount.

13

(1) current sales prices charged by the reporting entity in an active market;

(2) current sales prices charged by other vendors, e.g., competitors, in an active market, if (1) is not possible;

(3) current sales prices charged by the reporting entity in an inactive market, if (1) and

(2) are not possible; or

(4) estimates reflecting entity-specific inputs, e.g., the reporting entity’s estimated

(average) costs plus a normal (average) profit margin, if (1) to (3) are not possible.

Much like using valuation models to construct fair values, measurement of estimated sales prices on level (4) is assumed to meet general reliability thresholds (IASB, 2004i,

2005c). If there is a difference between the total customer consideration and the aggregate of estimated sales prices of performance obligations considered, the (positive or negative) residual shall be allocated to the performance obligations pro rata based on their estimated sales prices. This yields a measurement according to the allocated consideration amount, which will ensure that no revenue is recognised at contract inception in general. According to recent proposals, performance obligations shall not be remeasured under the alternative approach (IASB, 2005g).

While the FASB favours to measure all performance obligations at their allocated consideration amount, the IASB prefers to exclude (i) unconditional stand ready obligations and (ii) obligations required to be measured at fair value by a given standard

8 These obligations shall be measured at fair value and no

residual shall be allocated to them. Moreover, it is proposed to allow or to require to measure performance obligations at their fair value if an active market exists (IASB,

2005b, 2005c). This would result in a mixed approach

. Two implications of the mixed approach are noteworthy. First, given the case that all performance obligations arising from a contract can or are to be measured at their fair value, the mixed approach shows results equal to the fair value approach. Particularly, revenue will have to be recognised at contract inception if there is a residual that must not be allocated to the obligations.

Second, if some performance obligations are measured at their fair value, their remeasurement can c.p. again give rise to volatility in earnings depending on the proportion of obligations remeasured at their fair value.

8 The FASB and the IASB took different (tentative) decisions in this regard.

14

4 Discussion

4.1

Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Information

Relevance

Unlike present IFRSs, the proposals of the project

Revenue Recognition

rely on a conceptual model by following an asset-liability approach. The traditional realisation principle shall no longer serve as a rule to determine income. The SEC even claims that the asset-liability approach “most appropriately anchors the standard setting process by providing the strongest conceptual mapping to the underlying economic reality” (FASB and IASB, 2005: 8).

Conceptual findings support this view given that a current or market value based assetliability approach shall approximate economic income and provide future-orientated information, generally assessed to be relevant to estimate future profitability of the investment. In particular, the project envisages showing the size of orders from enforceable contracts in the balance sheet. Even compared to the (voluntary) disclosure of the information in the notes, research findings suggest that presentation in the balance sheet is more value relevant (e.g., for analytical evidence Barth, Clinch and

Shibano, 2003; for empirical findings Hirst and Hopkins 1998; Maines and McDaniel,

2000).

If we maintain contract inception as relevant, particularly timely date for recognising assets and liabilities, (i) initial and (ii) subsequent measurement of items recognised must be discussed. Following the fair value approach, revenue or expense is recognised at contract inception if the initial sum of fair values of performance obligations does not equal the consideration amount both parties agreed on. As an irritating consequence a loss can occur at contract inception although performing the whole contract leads to a profit and vice versa. This provides a biased indicator of future performance, thereby potentially misleading investors. Initial measurement of performance obligations at their allocated consideration amount mitigates this concern as contract inception does not

9 See the Appendix for an example.

15

Analytical and empirical findings do not unambiguously support the relevance of fair values, particularly if market prices are not observable. Fair value remeasurement is known to reflect market valuation leading to valuation-based volatility in profit or loss apart from specific performance (Ballwieser, 2004). Relevance of hypothetical liability extinguish values must be questioned if performance extinguishment is legally prohibited, not intended or actually not transacted by the reporting entity. There is neither specific theoretical work nor empirical evidence on allocated consideration amounts. As they base on estimated sales prices comparable to an exit (fair) value, the above results may merely be transferred if there are no or little residuals allocated to the performance obligations. However, allocated consideration amounts smooth differences between the sum of estimated sales prices and the total consideration in absence of subsequent remeasurement.

10 This could be relevant given evidence that earnings

smoothing can provide relevant information (e.g., Arya, Glover, and Sunder, 2003;

Tucker and Zarowin, 2005).

While the project does not intend to link revenue recognition to realisation or earnings criteria, conceptual, analytical and empirical evidence finds that disaggregating income components according to these criteria provides relevant information (e.g., for conceptual results Edwards and Bell 1961; for analytical results Ohlson, 1999; for empirical results Garrod, Giner, and Larran, 2000; Brown and Sivakumar, 2003; Biddle and Choi, 2003). This, e.g., implies to separately present elements arising from remeasurement in an income statement. If expenses follow from remeasurement and are aggregated with costs of performance, the latter are not visible in the statement of

(comprehensive) income. In similar vain, a distinction of pre- and post-performance assets or liabilities in the balance-sheet requires a definition of performance date which

is not independent from realisation or earnings criteria.

11 This suggests that realisation

or earnings criteria might not be fully negligible at least for presentation.

10 Considering a construction contract, any multiplicative transformation of the vector of estimated sales prices (with the multiplier differing from zero) yields an equal vector of allocated customer consideration amounts of the performance obligations. However, a variation between the estimated

11 sales prices impacts the allocation of the residual.

See also Ernstberger (2005), who proposes a combined model.

16

Reliability

The assessment of (i) inception date of a contract and (ii) the measurement of performance obligations requires managerial judgement. This is ambivalent: The manager can reveal relevant (private) information or exercise self-serving discretion. As reliability of information can be seen as a prerequisite for relevance, evaluating relevance must incorporate reliability considerations.

According to the proposals, an enforceable contract shall give rise to assets and liabilities. While contract inception appears to be an objective formal reference at first glance, referring to customer business practice allows for discretion (Wüstemann and

Kierzek, 2005). As contract inception can change financial ratios, the proposal allows for short-term window-dressing. Particularly, the fair value approach can give rise to real earnings management by contract inception.

The measurement bases for performance obligations challenge reliability and allow for accounting earnings management in many cases. The difficulties in determining fair values particularly of non-financial liabilities are known (e.g., Martin and Tsui, 1999;

Ernst & Young, 2005). If there are no market prices, hypothetical fair values are constructed using valuation models and incorporating managerial subjectivity. In similar vain, estimated sales prices as basis for allocated consideration amounts can be criticised. In both cases, referring to prices charged by other vendors is critical in absence of active markets, while a mixed approach will incorporate additional discretion in absence of a strict distinction of measurement bases for performance liabilities.

Remeasuring performance obligations (at either value) requires judgement in each period and allows for changing accounting earnings management strategies within the borders of consistency. As to date, the boards do not intend to remeasure allocated consideration amounts, the vector of contractual revenues is determined by measurement at contract inception in this approach.

Potential consequences of the above reliability issues, particularly referring to measurement, concern audit and litigation. First, credible reporting of items at their fair values or allocated consideration amounts can enhance the need for audit. The audit, however, reduces to testing the plausibility of estimation techniques and arguments in absence of observable market prices. Second, the threat of litigation can put cost on

17 reporting entities and on auditors (Siegel, 1997), who might shift rising costs to his client.

Comparability

Accounting choice can impair comparability of financial statements (i) of different reporting entities and (ii) of different periods (consistency), thereby affecting understandability. Apart from the discussed disaggregation of contractual liabilities and separation of revenues, the tentative decisions taken on initial recognition and measurement post problems with comparability.

Different interpretations of the inception date of an enforceable contract can lead to incomparability. From an economic point of view, customer business practice varies among entities. From a legal point of view, the understanding of contract inception varies among jurisdictions (Wüstemann and Kierzek, 2005). As the link to customer business practice is based on substance over form and different legal frameworks are outside the scope of IFRSs, inter-firm comparability is hard to establish in these regards.

Although the assessment allows to bring forward or to postpone initial recognition of contractual assets and liabilities and, in the fair value approach, of revenue or expense, a consistent assessment mitigates the feasible window-dressing and earnings management.

Judgement and subjectivity in measuring performance obligations affects comparability.

Literature has shown that fair value measurement allows for discretion which can be exercised in different ways among entities. Measuring estimated sales prices yields similar problems. Any judgement or alternative to measure performance obligations at their fair value or their allocated consideration challenges comparability. Even if the amounts recognised are measured by a consistent approach, remeasurement of performance obligations can lead to volatility of revenues and profits impairing their comparability among periods.

18

Understandability

Consistent with the above problems of fair value accounting, parts of the literature express concerns whether users understand that and how fair values are constructed in absence of prices on active markets (Ernst & Young, 2005; Belkaoui, 2000; for banks

Swanney, 1999). As even the IASB recognises that many performance obligations will be measured on level (3) of the fair value hierarchy, the concern might substantiate, at least in absence of adequate explanatory information. Similar doubts can concern the construction of estimated sales price on level (4) of the hierarchy. Given prior literature criticising a mixture of values (e.g., Haller and Schloßgangl, 2005), measuring some performance obligations at their fair values and others at their allocated consideration amounts might be obscure for financial statement users.

4.2

Objectives of Financial Reporting

Decision Usefulness

The above results imply that the current proposals do not fully meet the qualitative characteristics constituting decision usefulness according to the framework.

Recognising assets and liabilities at contract inception can provide future-orientated information useful for economic decisions. The fair value approach measures profitability in relation to market prices, whereas the allocated consideration amount approach uses (consideration-matched) estimated sales prices as a benchmark. While analytical and empirical evidence does not unambiguously support the decision usefulness of fair value accounting, we lack specific findings on allocated consideration amounts. Apart from missing consistent or sound theoretical evidence on relevance, both approaches rely on hypothetical transactions and on hypothetical prices in absence of active markets. In particular, this challenges the reliability and, in turn, the relevance of revenue recognition. At least the relevance-reliability trade-off questions that the new models of revenue recognition actually enhance decision usefulness.

19

Stewardship

Interpreting stewardship as a sub-objective of decision usefulness yields results equal to those above. But stewardship can be considered in the light of impact the accounting system has on the manager’s decisions.

In compensating the manager partly by bonus payments depending on income, incentives for managers are created to increase profits. When using the fair value approach, profit or loss is anticipated relative to the sum of extinguishment values at inception date. A profit occurs when the fair value of the performance obligation is lower than the total customer consideration. At contract inception, the manager is rewarded for the positive result. Although a profit can result overall, losses can be

recognised in the intermediate periods because expenses exceed revenues.

are created to close contracts that lead to high profits at inception if the manager plans to leave the company. But ass any excess of the sum of fair values of performance obligations over the consideration amount shall be recognised as expense in the period of contract inception managerial incentives to inflate revenues by contracting at dumping prices are limited. In similar vain, there are incentives to calculate upwardbiased fair values for the performance obligations first extinguished. In the reverted case, if a loss results at contract inception with profits recognised later on, the manager is punished at contract inception although an overall profitable contract is placed. The loss might lead to a dismissal of the manager because of poor performance. Likewise, the manager might not be willing to close these kinds of contracts especially if he leaves the company soon, because his bonus payments decrease with the loss recognised

(Jensen and Smith 1985; Ballwieser, 1997; for an overview Pfeiffer, 2003). The bottomline figure is not a good indicator for the performance of the manager and can bias the decision of the investors regarding the employment of the manager. The fair value model is, thus, far from measuring manager performance. It contradicts to analytical evidence where conservative accounting is identified as superior for creating the right incentives (Wagenhofer 1996; Baldenius and Reichelstein, 2000; Dutta and Zhang,

2002). If the IASB decides to remeasure fair values in subsequent periods, results are getting volatile. The manager is not compensated on actual performance since market

12 See the Appendix for an example.

20

prices are a result of supply and demand and are subject to different factors.

might thwart the desired results for investors.

The allocated consideration amount approach recurs to the amounts fixed in the contracts. At inception date, asset and liability are recognised at the same amount and do not lead to any profit or loss. In the subsequent periods, the decrease of the contract

liabilities indicates the stage of completion relative to estimated sales prices.

model appears to reflect performance better compared to the fair value model. If profits are allocated according to the progress of the project, the manager is compensated accordingly. This can create incentives to engage in long-term projects. But if the manager intends to quit the company, there are still incentives to calculate upward biased estimated sales prices for the performance obligations first performed, which are then allocated a larger proportion of the positive residual. In the reverted case where a negative residual has to be allocated, there are incentives to calculate upward- or downward-biased estimated sales prices for these obligations depending on the amount of the residual to be allocated relative to the sales prices to be estimated.

Both approaches use estimated values if market prices do not exist. Judgement is necessary to compute the fair value or the allocated consideration amounts. For compensation and stewardship purposes, the figure used for compensation should be controllable but not manipulable by the manager. If the manager can influence the values by making changes in the assumptions for future cash flows or interest rates, he is able to increase his salary. The user is probably not able to detect this procedure. If the user knows about the influence of the manager on the amounts reported, he will not be willing to accept the figures as basis for compensation.

13 The controllability principle says that the manager should only be accountable for resources under

14 his control (Choudhury, 1986).

See the Appendix for an example.

21

4.3

Regulative Compatibility

Current Regulations of the IASB and IASCF

The preceding two sections have cast doubt on the current proposals with regard (i) to qualitative characteristics of information and (ii) to the objectives of financial reporting.

Given the above assessment of both criteria the proposals conflict with

(1) IAS 1 which aims at decision useful information (IAS 1.7) and fair presentation

(IAS 1.13);

(2) the Framework of the IASB regarding objectives (F.12-20) and qualitative characteristics of financial information (F.24-46);

(3) the Constitution of the IASCF, aiming to develop “high quality, understandable and enforceable global standards” requiring high quality, transparent, and comparable information for supporting economic decisions (C.2(a)).

The aim of convergence, explicitly set out in the objectives of the project and implied by the Constitution of the IASCF, manifests the importance of the FASB’s position. The

FASB can exercise pressure on the IASB in the joint project currently revealed with regard to measuring performance obligations at the customer consideration amount instead of the fair value. Concerning the Framework, the current proposals of the project

Revenue Recognition

do not require a probability criterion for the recognition of contractual assets and liabilities which conflicts with the definitions in F.49(a) and (b).

This issue, however, is to be addressed in another joint project revising the framework

(FASB and IASB, 2005).

Other Projects of the IASB

Given the ongoing evolution of IFRSs, compatibility of projects conducted is a major issue for developing a consistent set of (future) standards. An adequate Framework should be the conceptual basis for consistently developing new or revising existing standards (Miller, Redding, and Bahnson, 1998; Nobes and Parker, 2004). However, the

Framework of the IASB cannot fulfil its intended function as it is dated, inconsistent and currently under revision.

22

A controversial point at issue is initial and subsequent measurement of liabilities arising from performance obligations. The IASB’s vote to measure performance obligations at their fair value is consistent with the proposed amendments to IAS 37

which imply to measure non-financial liabilities at their fair value (IASB, 2005k). However, wholly or partially using the allocated consideration amount as preferred by the FASB will cause incompatibility of recent developments of liability measurement at the IASB.

The project

Insurance Contracts (Phase II)

has not yet made decisions on concept, recognition, and measurement. But there is a preference (i) for an asset-liability approach, which is consistent with the current proposals on revenue recognition, and (ii) for not to allow for profit or loss at contract inception particularly in life-insurance, which is inconsistent with the proposed model measuring performance obligations at their fair value (Anon., 2005; IASB, 2005d). While potential incompatibilities could be reasoned by particularities of the insurance industry, the revenue recognition project might have benefited from a link to the insurance project which discussed a fair value based asset-liability approach at an earlier stage.

The proposed approaches for revenue recognition are complex and costly, e.g., directly concerning the disaggregation of contractual obligations, the construction of fair values or the allocation of consideration and indirectly concerning litigation or audit (Dobler,

2006). Given that the IASB’s project on

Accounting Standards for Small and Mediumsized Entities

aims at mitigating cost burdens by applying (modified) IFRSs (IASB,

2004j), a standard based on the recent proposals is not capable for SMEs. In consequence, there might be diverging rules for SMEs and entities applying full IFRSs

at the core of accounting, i.e., revenue recognition.

undermine the IASCF’s objective to develop a single set of financial reporting standards

(C.2(a)).

Further inconsistencies can arise due to a missing link to the joint FASB/IASB project

Performance Reporting

which explores a new concept for presenting income and expense (IASB, 2005f). On the one hand, it is precarious to deal with the presentation of performance without having defined performance, of which revenue is a significant

15 Currently, the SME project does not intend major simplifications of IAS 11 and IAS 18 for SMEs apart from combining and segmenting contracts (IASB, 2005j).

23 element. On the other hand, the project

Revenue Recognition

shall address the distinction of revenues and gains. But the tentative proposals do not comply with the categorisation models currently discussed in the performance reporting project

(FASAC, 2005a). Both projects will impact the joint project

Conceptual Framework and the definitions of elements of financial statements (FASB and IASB, 2005). This is perverse from a regulatory perspective given that the Framework is intended to provide a conceptual basis to develop consistent standards.

Endorsement Requirements of the EU

Apart from compliance considerations with existing regulations of the IASCF or the

IASB or other current projects, political pressure can influence the project

Revenue

Recognition

. While the FASB has significant impact concerning convergence, the EU might exert pressure on the IASB (i) ex post by not endorsing a standard according to the comitology procedure and (ii) ex ante by threatening to do so. According to Art.

3(2) of Regulation (EC) 1606/2002 (van Hulle, 2004), the adoption of an IFRS by the

EU requires the standard

(1) to “meet the criteria of understandability, relevance, reliability and comparability required of the financial information needed for making economic decisions and assessing the stewardship of management”; and

(2) not to conflict with Art. 2(3) of Directive 78/660/EEC and Art. 16(3) of Directive

83/349/EEC requiring financial statements to give “a true and fair view of the (...) assets, liabilities, financial position and profit or loss”.

The discussion has shown that the proposals do only partially comply with both the qualitative characteristics of financial information and the objectives of financial reporting required by criterion (1). Concerning criterion (2) the European true and fair view might differ from the true and fair view underlying the IFRSs, given the controversy even in interpreting true and fair view according to EC Directives

(Alexander, 1993; Burland, 1993; Ordelheide, 1993). At least from a continental, particularly a German point of view, the suppression of the European conservatism principle inherent to the fair value approach and merely mitigated in the approach based on allocated customer consideration amounts yields a conflict with EC Directives.

24

5 Concluding Remarks

This paper has analysed the concept of revenue recognition proposed by the project

Revenue Recognition

conducted by the IASB and the FASB based on conceptual, analytical, and empirical research findings. Results show conflicts with (i) qualitative characteristics of information and (ii) the objectives financial reporting, which are more severe in the fair value approach than in the allocated consideration approach. This yields incompatibilities with (i) aims of the IASCF constitution, the Framework, and

IAS 1, and, more importantly, with (ii) endorsement criteria of the EU.

While the standard-setter may discuss away some of the above conflicts, criteria as interpreted for EU endorsement can form a major obstacle for the proposals presented to date. Currently, working groups of the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group and the German Accounting Standards Board are developing an alternative approach consistent with the traditional European concept of revenue recognition. However, an extensive “dynamic” interpretation of the true and fair view set out in EC Directives might allow even current proposals of the project

Revenue Recognition

to meet the criteria for EU endorsement.

Unlike revenue recognition according to current IFRSs, the proposals are conceptbased. But neglecting developments in other IASB projects can provoke new inconsistencies in future IFRSs. This suggests to co-ordinate project activities, particularly concerning revenue recognition and performance reporting, more closely and to take a more comprehensive view on the concepts to be developed. The project debate sparks new interest on concepts of income, discussed in accounting literature for far more than one century. While existing research findings provide a rather sound basis for developing and evaluating the fair value approach, the allocated consideration amount approach remains to be addressed in more detail and provides an area for further conceptual and analytical research.

25

Literature

Ahmed, Anwer S., and Takeda, Carolyn (1995), Stock Market Valuation of Gains and

Losses on Commercial Banks’ Investment Securities – An Empirical Analysis,

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 20, 207-225.

Alexander, David (1993), A European true and fair view? European Accounting

Review, 2, 59-80.

Anon. (2006), CFO Forum – Principles for an IFRS Phase II Insurance Model, 21 July

2005, http://www.cfoforum.nl/phase_ii_principles.pdf.

Antle, Rick and Smith, Abbie J. (1985), Measuring Executive Compensation: Methods and an Application, Journal of Accounting Research, 23, 296-325.

Antle, Rick, and Demski, Joel S. (1989), Revenue Recognition, Contemporary

Accounting Research, 5, 423-451.

Arya, Anil, Glover, Jonathan C., and Sunder, Shyam (2003), Are Unmanaged Earnings

Always Better for Shareholders?, Accounting Horizons, 17, Supplement, 111-116.

Ashley, Allan S., and Yang, Simon S.M. (2004), Executive Compensation and Earnings

Persistence, Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 369-382.

Baber, William R., Kang, Sok-Hyon, and Kumar, Krishna R. (1998), Accounting

Earnings and Executive Compensation: The Role of Earnings Persistence, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25, 169-193.

Baber, William R., Kang, Sok-Hyon, and Kumar, Krishna R. (1999), The Explanatory

Power of Earnings Levels vs. Earnings Changes in the Context of Executive

Compensation, The Accounting Review, 74, 459-472.

Baetge, Jörg (1970), Möglichkeiten der Objektivierung des Jahreserfolges, Düsseldorf.

Baldenius, Tim, and Reichelstein, Stefan (2000), Incentives for Efficient Inventory

Management: The Role of Historical Cost, Working Paper, University of

California, Berkeley.

Ballwieser, Wolfgang (2004), The Limitations of Financial Reporting. In: Leuz,

Christian, Pfaff, Dieter, and Hopwood, Anthony (Eds.), The Economics and

Politics of Accounting, Oxford et al., 58-77.

Ballwieser, Wolfgang (1997), Chancen und Gefahren einer Übernahme amerikanischer

Rechnungslegung. In: Budde, Wolfgang-Dieter, Moxter, Adolf, and Offerhaus,

Klaus (Eds.), Handelsbilanzen und Steuerbilanzen, FS für Heinrich Beisse,

Düsseldorf, 25-44.

Ballwieser, Wolfgang, Küting, Karlheinz, and Schildbach, Thomas (2004), Fair value – erstrebenswerter Wertansatz im Rahmen einer Reform der handelsrechtlichen

Rechnungslegung?, Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis, 56, 529-549.

Barth, Mary E. (1994), Fair Value Accounting: Evidence from Investment Securities and the Market Valuation of Banks, The Accounting Review, 69, 1-24.

Barth, Mary E., and Landsman, Wayne R. (1995), Fundamental Issues Related to Using

Fair Value Accounting for Financial Reporting, Accounting Horizons, 9, 97-107.

Barth, Mary E., Beaver, William H., and Landsman, Wayne R. (1996), Value-

Relevance of Banks’ Fair Value Disclosures under SFAS No. 107, The

Accounting Review, 71, 513-537.

Barth, Mary E., Beaver, William H., and Landsman, Wayne R. (2001), The Relevance of the Value Relevance Literature for Financial Accounting Standard Setting:

Another View, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 77-104.

Barth, Mary E., Clinch, Greg, and Shibano, Toshi (2003), Market Effects of

Recognition and Disclosure, Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 581-609.

Belkaoui, Ahmed Riahi (2000), Accounting Theory. 4th edition, London.

26

Bernard, V.L., and Shipper, K. (1994), Recognition and Disclosure in Financial

Reporting, Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Biddle, Gary C., and Choi, Jong-Hag (2003), Is Comprehensive Income Useful?,

Working Paper, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Birnberg, Jacob G. (1980), The Role of Accounting in Financial Disclosure,

Accounting, Organization and Society, 5, 71-80.

Brown, Lawrence D., and Sivakumar, Kumar (2003), Comparing the Value Relevance of Two Operating Income Measures, Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 561-572.

Burlaud, Alain (1993), Commentaires sur l’article de David Alexander ‘A European true and fair view?’, European Accounting Review, 2, 95-104.

Bushman, Robert M., and Smith, Abbie J. (2001), Financial Accounting Information and Corporate Governance, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, 237-333.

Bushman, Robert M., Engel, Ellen, Milliron, Jennifer, and Smith, Abbie (1998), An

Empirical Investigation of Trends in the Absolute and Relative Use of Earnings in

Determining CEO Cash Compensation, Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Choudhury, Nandan (1986), Responsibility Accounting and Controllability, Accounting and Business Research, 16, 189-198.

Christensen, John A., and Demski, Joel S. (2003), Accounting Theory – An Information

Content Perspective, New York et al.

Christensen, Peter O., Feltham, Gerald A., and Ş abac, Florin (2005), A Contracting

Perspective on Earnings Quality, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 265-

294.

Clinch, G., and Magliolo, J. (1993), CEO Compensation and Components of Earnings in Bank Holding Companies, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 16, 241-272.

Dechow, Patricia M., and Sloan, Richard G. (1991), Executive Incentives and the

Horizon Problem – An Empirical Investigation, Journal of Accounting and

Economics, 14, 51-89.

Dobler, Michael (2006), Ertragsvereinnahmung bei Fertigungsaufträgen nach IAS 11 und nach den Vorschlägen des Projekts Revenue Recognition – Vergleich und kritische Würdigung. Zeitschrift für Kapitalmarktorientierte Rechnungslegung, 6, forthcoming

.

Dobler, Michael (2004), Risikoberichterstattung – Eine ökonomische Analyse,

Frankfurt am Main.

Dutta, Sunil, and Reichelstein, Stefan (2005), Stock Price, Earnings, and Book Value in

Managerial Performance Measures, The Accounting Review, 80, 1069-1100.

Dutta, Sunil, and Reichelstein, Stefan (1999), Asset Valuation and Performance

Measurement in a Dynamic Agency Setting, Review of Accounting Studies, 4,

235-258.

Dutta, Sunil, and Zhang, Xiao-Jun (2002), Revenue Recognition in a Multiperiod

Agency Setting, Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 67-83.

Dye, Ronald A., and Sridhar, Sri S. (2004), Reliability-Relevance Trade-Offs and the

Efficiency of Aggregation, Journal of Accounting Research, 42, 51-88.

Eccher, Elizabeth A., Ramesh, K., and Thiagarajan, S. Ramu (1996), Fair Value

Disclosures by Bank Holding Companies, Journal of Accounting and Economics,

22, 79-117.

Edwards, Edgar O., and Bell, Philip W. (1961), The Theory and Measurement of

Business Income, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London.

Ernst & Young (2005), How Fair is Fair Value?, London.

Ernstberger, Jürgen (2005), Revenue Recognition – A Conceptual Review of the

Proposed Model of the IASB, paper presented at the Workshop Accounting in

Europe 2005 and Beyond in Regensburg, September 2005.

27

FASB (2005b), Project Updates: Revenue Recognition, 2.12.2005.

FASB (2005a), Revised Minutes: Revenue Recognition, 30.9.2005.

FASB (2004b), Minutes: Revenue Recognition, Joint FASB/IASB Board Meeting

29.10.2004.

FASB (2004a), Minutes: Revenue Recognition, 25.2.2004.

FASB (2003), Minutes: Revenue Recognition, 28.2.2003.

FASB (2002), Minutes: Revenue Recognition, Joint FASB/IASB Board Meeting

25.9.2002.

FASB and IASB (2005), Revisiting the Concepts: A New Conceptual Framework

Project, May 2005.

FASAC (2005b), Summary of Responses to the Annual FASAC Survey: Priorities of the Financial Accounting Standards Board, October 2005.

FASAC (2005a), Financial Reporting by Business Entities, June 2005.

Fisher, Irving (1906), The Nature of Capital and Income, New York.

Franke, Günter, and Hax, Herbert (2004), Finanzwirtschaft des Unternehmens und

Kapitalmarkt, 5th edition, Berlin et al.

GAO (2002), Financial Statement Restatements – Trends, Market Impacts, Regulatory

Responses, and Remaining Challenges, Report GAO-03-138, Washington.

Garrod, N., Giner, B., and Larran, M. (2000), The Value Relevance of Earnings, Cash

Flow and Accruals: The Impact of Disaggregation and Contingencies, Working

Paper 2000/4, Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Glasgow.

Gaver, Jennifer J., and Gaver, Kenneth M. (1998), The Relation Between Nonrecurring

Accounting Transactions and CEO Cash Compensation, The Accounting Review,

73, 235-253.

Gjesdal, Frøystein (1981), Accounting for Stewardship, Journal of Accounting

Research, 19, 208-231.

Graham, Roger C., Lefanowicz, Craig E., and Petroni, Kathy R. (2003), The Value

Relevance of Equity Method Fair Value Disclosures, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 30, 1065-1088.

Haller, Axel, and Schloßgangl, Maria (2005), Shortcomings of performance reporting under IAS/IFRS: a conceptual and empirical study, International Journal of

Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 2, 281-299.

Hettich, Silvia (2006), Zweckadäquate Gewinnermittlungsregeln, Frankfurt am Main, forthcoming

.

Hirst, D.E., and Hopkins, P.E. (1998), Comprehensive Income Reporting and Analysts’

Valuation Judgment, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 36, Supplement, 47-

75.

Holmström, Bengt, and Milgrom, Paul (1987), Aggregation and Linearity in the

Provision of Intertemporal Incentives, Econometrica, 55, 303-328.

Hunt, Steven C. (1995), A Review and Synthesis of Research in Performance

Evaluation in Public Accounting, Journal of Accounting Literature, 15, 107-139.

IASB (2005k), Exposure Draft Proposed Amendments to IAS 37 Provisions,

Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets and IAS 19 Employee Benefits.

IASB (2005j), Information for Observers: Financial Reporting by Small and Mediumsized Entities, Overview of Responses and Recommendations on Possible

Recognition and Measurement Simplifications, November 2005.

IASB (2005i), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

19.10.2005.

IASB (2005h), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

20.9.2005.

28

IASB (2005g), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

22.-23.6.2005.

IASB (2005f), Project Update: Performance Reporting, 8.12.2005.

IASB (2005e), Project Update: Revenue Recognition, December 2005.

IASB (2005d), Project Update Insurance Contracts Phase II, 21.10.2005.

IASB Update, October 2005c.

IASB Update, September 2005b.

IASB Update, June 2005a.

IASB (2004j), Preliminary Views on Accounting Standards for Small and Mediumsized Entities.

IASB (2004i), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

22.6.2004.

IASB (2004h), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

17.-19.3.2004.

IASB (2004g), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

18.-20.2.2004.

IASB Insight, October/November 2004f.

IASB Insight, January 2004e.

IASB Update, July 2004d.

IASB Update, June 2004c.

IASB Update, February 2004b.

IASB Update, January 2004a.

IASB (2003e), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

17.12.2003.

IASB (2003d), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

17.-19.9.2003.

IASB (2003c), Information for Observers: Revenue Recognition, Board Meeting

19.-21.2.2003.

IASB Insight, January 2003b.

IASB Update, July 2003a.

IASB Update, September 2002.

Ijiri, Yuji (1970), A Defense of Historical Cost Accounting. In: Sterling, Robert R.

(Ed.), Asset Valuation and Income Determination, Houston, 1-14.

Ijiri, Yuji C. (1975), Theory of Accounting Measurement. Sarasota.

Jensen, Michael C., and Murphy, Kevin J. (1988), Performance Pay and Top

Management Incentives, in: JPE, Vol. 98, S. 225-264.

Jensen, Michael C., and Smith, Clifford W. Jr. (1985), Stockholder, Manager, and

Creditor Interests: Applications of Agency TheoryIn: Altman, Edward I., and

Subrahmanyam, Marti G. (Eds.), Recent Advances in Corporate Finance,

Homewood, 93-131.

Khurana, Inder K., and Kim, Myung-Sun (2003), Relative Value Relevance of

Historical Cost vs. Fair Value: Evidence from Bank Holding Companies, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22, 19-42.

Kirschenheiter, Michael (1997), Information Quality and Correlated Signals, Journal of

Accounting Research, 35, 43-59.

Kuhn, Klaus (1966), Die dynamische Bilanz als Führungsinstrument im Konzern,

Schmalenbachs Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 18, 563-567.

29

Kwon, Young K. (2004), Conservative Accounting as a Means to Control Suboptimal

Management Decisions in Public Firms, Paper presented at the 15th Annual

Conference on Financial Economics and Accounting, 19.-20.11.2004, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, http://www.usc.edu/schools/business/FBE/

FEA2004/FEApapers/A-S1B_YKWON.pdf.

Kwon, Young K. (1989), Accrual versus Cash-Basis Accounting Methods: An Agency-

Theoretic Comparison, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 8, 267-281.

Kwon, Young K., Newman, D. Paul, and Suh, Young S. (2001), The Demand for

Accounting Conservatism for Management Control, Review of Accounting

Studies, 6, 29-51.

Laux, Helmut (1995), Erfolgssteuerung und Organisation. 1. Anreizkompatible

Erfolgsrechnung, Erfolgsbeteiligung und Erfolgskontrolle, Berlin et al.

Leffson, Ulrich (1966), Wesen und Aussagefähigkeit des Jahresabschlusses,

Schmalenbachs Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 18, 375-390.

Leuz, Christian (1998), The Role of Accrual Accounting in Restricting Dividends to

Shareholders, European Accounting Review, 7, 597-604.

Liang, Pierre Jinghong (2000), Accounting Recognition, Moral Hazard, and

Communication, in: Contemporary Accounting Research, 17, 457-490.

Lindahl, Erik (1919), Die Gerechtigkeit der Besteuerung, Lund.

Maines, Laureen A., and McDaniel, Linda S. (2000), Effects of Comprehensive-Income

Characteristicts on Nonprofessional Investors’ Judgments: The Role of Financial-

Statement Presentation Format, The Accounting Review, 75, 179-207.

Martin, Greg, and Tsui, David (1999), Fair Value Liability Valuations, Sidney.

Miller, Paul B. W., Redding, Rodney J., and Bahnson, Paul R. (1998), The FASB – The

People, the Process, and the Politics. 4th edition, Boston et al.

Moxter, Adolf (1962), Der Einfluß von Publizitätsvorschriften auf das unternehmerische Verhalten. Köln/Opladen.

Natarajan, Ramachandran (1996), Stewardship Value of Earnings: Additional Evidence on the Determinants of Executive Compensation, The Accounting Review, 71,

1-22.

Nelson, Karen K. (1996), Fair Value Accounting for Commercial Banks: An Empirical

Analysis of SFAS No. 107, The Accounting Review, 71, 161-182.

Nobes, Christopher, and Parker, Robert (2004), Comparative International Accounting,

8th edition. London et al.

Ohlson, James A. (1999), On Transitory Earnings, Review of Accounting Studies, 4,

145-162.

Ordelheide, Dieter (1993), True and fair view – A European and a German perspective.

European Accounting Review, 2, 81-90.

Park, Myung S., Park, Taewoo, and Ro, Byung T. (1999), Fair Value Disclosures for

Investment Securities and Bank Equity: Evidence from SFAS 115, Journal of

Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 14, 347-370.

Paton, W.A., and Littleton, A.C. (1955), An Introduction to Corporate Accounting

Standards. American Accounting Association Monograph No. 3, 6th print, Ann

Arbor.

Petroni, Kathy Ruby, and Wahlen, James Michael (1995), Fair Values of Equity and

Debt Securities and Share Prices of Property-Liability Insurers, The Journal of

Risk and Insurance, 62, 719-737.

Pfeiffer, Thomas (2003), Anreizkompatible Unternehmenssteuerung, Performancemaße und Erfolgsrechnung – Zur Vorteilhaftigkeit von Ergebnisgrößen bei unbekannten

Zeitpräferenzen des Managers, Die Betriebswirtschaft, 63, 43-59.

30

Reichelstein, Stefan (2000), Providing Managerial Incentives: Cash Flows versus

Accrual Accounting, Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 243-269.

Rogerson, William P. (1997), Intertemporal Cost Allocation and Managerial Investment

Incentives: A Theory Explaining the Use of Economic Value Added as a

Performance Measure, Journal of Political Economy, 105, 770-795.

Siegel, Stanley (1997), The Coming Revolution in Accounting: The Emergence of Fair

Value as the Fundamental Principle of GAAP, Wirtschaftsprüferkammer-

Mitteilungen, 36, Supplement June, 81-90.

Simko, Paul J. (1999), Financial Instrument Fair Values and Nonfinancial Firms,

Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 14, 247-274.

Sloan, Richard G. (1993), Accounting Earnings and Top Executive Compensation,

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 16, 55-100.

Smith, Adam (1890), An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,

London.

Solomons, David (1961), Economic and Accounting Concepts of Income, The

Accounting Review, 36, 374-383.

Swanney, David (1999), Fair Values: A Bank Supervisor’s Perspective, IASC Insight,

December 1999.

Tucker, Jenny, and Zarowin, Paul (2005), Does Income Smoothing Improve Earnings

Informativeness?, Working Paper, New York University and University of

Florida.

van Hulle, Karel (2004), From Accounting Directives to International Accounting

Standards. In: Leuz, Christian, Pfaff, Dieter, and Hopwood, Anthony (Eds.), The

Economics and Politics of Accounting, Oxford et al., 349-375.

Venkatachalam, Mohan (1996), Value-Relevance of Banks’ Derivatives Disclosures,

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 22, 327-355.

Wagenhofer, Alfred (1996), Vorsichtsprinzip und Managementanreize, Schmalenbachs

Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 48, 1051-1074.

Wagenhofer, Alfred, and Ewert, Ralf (2003), Externe Unternehmensrechnung, Berlin et al.

Wampler, B. M., and Posey, C. L. (1998), Fair Value Disclosures and Share Prices:

Evidence from the Banking Industry, Advances in Accounting, 16, 253-267.

Wüstemann, Jens, and Kierzek, Sonja (2005), Erfolgsvereinnahmung im neuen

Referenzrahmen von IASB und FASB – internationaler Abschied vom

Realisationsprinzip?, Betriebs-Berater, 60, 427-434.

31

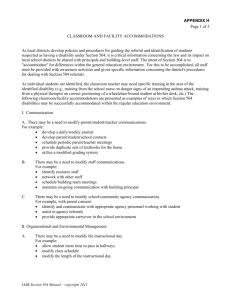

Appendix: Illustrative Examples

While construction contracts are not expressively mentioned as a motivation for the joint project, they provide a unique example to illustrate the consequences of the proposed models on the timing of revenue recognition, which are invisible in single-period examples. For simplicity, we do not consider (i) problems of disaggregating performance obligations, (ii) remeasurement of performance assets and liabilities, (iii) post-performance stand-ready obligations and (iv) deferred taxes. For the following examples see Dobler (2006).

Suppose a reporting entity which incepts an enforceable contract in t

125 MEUR. From t

1

to t

4

0

with total customer consideration of

the entity performs a separate performance obligation in each period. Contract costs are 20 MEUR in t of 100 MEUR. In t

4

1

, 24 MEUR in t

2

, 28 MEUR in t

3

and 28 MEUR in t

4

, yielding total contract costs

the customer accepts the work and is charged 125 MEUR.

Example A – Stage-of-Completion-Method

Suppose that under IAS 11 the outcome of the construction contract can be estimated reliably (IAS

11.23), the stage-of-completion-method must me applied (IAS 11.22), and the stage of completion is determined by reference to contract costs incurred for work performed (IAS 11.30(a)).

Revenue

Expense

Gross Profit

Contract Asset

Contract Liabilities -

-

t

0

-

-

5

25

t

1

25

20

6

55

t

2

30

24

7

90

t

3

35

28 t

4

35

28

7

125

-

Sum

125

100

25

Example B – Fair Value Approach

B1.