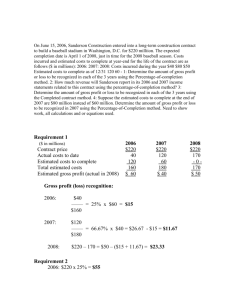

Revenue and Expense Recognition

advertisement