Close Reading Handout

advertisement

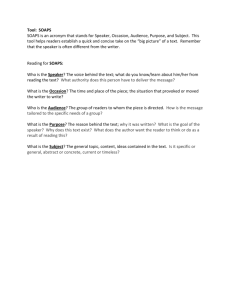

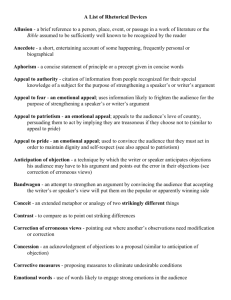

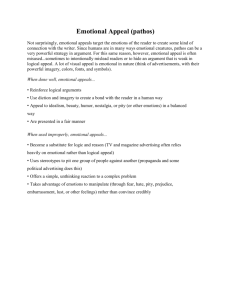

Tool: SOAPS SOAPS is an acronym that stands for Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, and Subject. This tool helps readers establish a quick and concise take on the “big picture” of a text. Remember that the speaker is often different from the writer. Reading for SOAPS: Who is the Speaker? The voice behind the text; what do you know/learn about him/her from reading the text? What authority does this person have to deliver the message? What is the Occasion? The time and place of the piece; the situation that provoked or moved the writer to write? Who is the Audience? The group of readers to whom the piece is directed. How is the message tailored to the specific needs of a group? What is the Purpose? The reason behind the text; why it was written? What is the goal of the speaker? Why does this text exist? What does the author want the reader to think or do as a result of reading this? What is the Subject? The general topic, content, ideas contained in the text. Is it specific or general, abstract or concrete, current or timeless? The River-Merchant's Wife: A Letter by Ezra Pound While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead I played about the front gate, pulling flowers. You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse, You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums. And we went on living in the village of Chokan: Two small people, without dislike or suspicion. At fourteen I married My Lord you. I never laughed, being bashful. Lowering my head, I looked at the wall. Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back. At fifteen I stopped scowling, I desired my dust to be mingled with yours Forever and forever and forever. Why should I climb the look out? At sixteen you departed, You went into far Ku-to-yen, by the river of swirling eddies, And you have been gone five months. The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead. You dragged your feet when you went out. By the gate now, the moss is grown, the different mosses, Too deep to clear them away! The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind. The paired butterflies are already yellow with August Over the grass in the West garden; They hurt me. I grow older. If you are coming down through the narrows of the river Kiang, Please let me know beforehand, And I will come out to meet you As far as Cho-fu-Sa. By Rihaku I Am Offering This Poem to You by Jimmy Santiago Bace, from Immigrants in Our Own Land I am offering this poem to you, since I have nothing else to give. keep it like a warm coat when winter comes to cover you, or like a pair of thick socks the cold cannot bite through, I love you. I have nothing else to give you, so it is a pot full of yellow corn to warm your belly in winter, it is a scarf for your head, to wear over your hair, to tie up around your face, I love you. Keep it, treasure this as you would if you were lost, needing direction, in the wilderness life becomes when mature: and in the corner of your drawer, tucked away like a cabin or Hogan in dense trees, come knocking, and I will answer, give you directions, and let you warm yourself by this fire, rest by this fire, and make you feel safe, I love you. It’s all I have to give, and all anyone needs to live, and to go on living inside, when the world outside no longer cares if you live or die; remember, I love you. The Close Reading Classroom- Making Connections- Four fundamental ways we relate to text. Text to Self: How does this text relate to me? Text to Itself: What are the distinguishing features of this text? How did this aid in comprehension of the text? Text to Text: How is this text similar to other texts? Text to World: Why does it matter for people to read this text? Three Levels of Questions Level One Questions: The answers to these questions can be found explicitly in the text. These are most often who, what, when, and where kinds of questions. They work on the factual level and establish evidence of basic information. Level Two Questions: The answers to these questions are not found explicitly in the text – the reader has to infer, interpret, or analyze. They are what the text suggests but does not say. These are often how and why questions. Level Three Questions: The answers to these questions go beyond the text and are often found in parallel situations outside the text. The reader has to analyze, synthesize, and/or evaluate, using the text as a guide to explore larger issues. They often require outside knowledge or experience to answer. Appeals – Logical, Ethical, Emotional A writer or speaker uses logical, ethical, and emotional appeals (or, in Aristotle’s words, logos, ethos, and pathos) to convince or persuade. A writer may use one, several, or a combination of these. The most effective combination of appeals is the emotional appeal that comes after the logical and/or ethical appeal(s). In order to effectively use an appeal, the writer or speaker needs to keep the audience in mind. Logical or Rational (logos): This is an appeal to the reader’s use of pure reasoning, that is, that which is indisputably rational or logical. You utilize a logical appeal by having a strong claim and moving through a series of related subclaims, each supported by strong evidence. You also acknowledge the claims and/or evidence of the other side and therefore present an argument that is balanced or “objective.” Ethical (ethos): An ethical appeal conveys the expertise or good reputation of the speaker through the use of evidence and tone. A rational appeal shows that the speaker or writer is thinking logically and fairly, and an ethical appeal establishes credibility and goodwill. A speaker or writer using ethical appeal can (1) invoke the common values or ideals of the audience and (2) remind the audience of their good character, relevant experience, or expertise. Emotional (pathos): This appeal aims directly for the listener or speaker’s hearts by tapping into the deep-seated feelings and beliefs we share as humans. An emotional appeal may be explicit as or it may be less obvious when the writer or speaker chooses words that suggest or slant the bias in a certain direction. Assumptions An assumption is a fact or statement taken for granted by writers or speakers that they sometimes make explicit as a way to effectively argue their point and anticipate what is in the reader’s or listener’s mind. Sometimes, assumptions are not revealed and remain implicit, and it becomes the reader’s or listener’s job to look for the underlying assumptions behind an argument. One critical aspect of assumptions is that they can also be errors in logical thinking. It is important not only for students to practice finding the assumptions behind a writer’s or speaker’s thinking but also to determine the validity of the assumption.