Market Demand Analysis Report for the Citywide

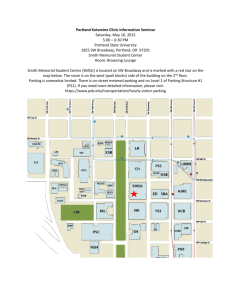

advertisement