Title The Construction of Request Discourse: A Preliminary Study of

advertisement

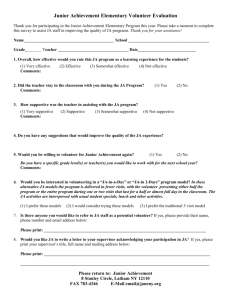

Title Author(s) Journal Issue Date Type The Construction of Request Discourse: A Preliminary Study of the Use of Superiors' Supportive Moves in SuperiorSubordinate Interactions in the Japanese Workplace Saito, Junko Sophia linguistica : working papers in linguistics, (59) 2012-07-05T02:31:45Z 紀要/Departmental Bulletin Paper Text Version 出版者/Publisher URL Rights http://repository.cc.sophia.ac.jp/dspace/handle/123456789/345 47 The Construction of Request Discourse: A Preliminary Study of the Use of Superiors’ Supportive Moves in Superior-Subordinate Interactions in the Japanese Workplace Junko SAITO Summary Although research on Japanese superiors’ directive usage in workplaces has been extensive, none of this research focuses specifically on the request speech act. Furthermore, even previous research that does include some mention of request speech acts has not closely examined actual request discourse in naturally occurring settings. To fill these gaps in the current research, this study empirically examines how request discourse is constructed in spontaneous superior-subordinate interactions in a workplace, particularly focusing on male superiors’ use of linguistic devices that modify the illocutionary force of the request, namely, supportive moves (Blum-Kulka, House & Kasper 1989, p.17). The study reveals that the superiors skillfully manipulate supportive moves so as to mitigate the force of their requests, and that interactive patterns of the request speech act vary depending upon multiple contextual parameters, such as the domain of the subordinates’ work duties and superiors’ perception of uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) membership categorization, among others. Because it investigates only a single workplace with limited occurrences of request discourse, I consider this a preliminary study. 1. Introduction There has been extensive research examining directive usage in Japanese workplace discourse in naturally occurring settings (e.g. Furo 1996; Sunaoshi 1994; Takano 2005). However, much of this research primarily focuses on linguistic practices that female superiors in an institutional hierarchy exercise; none of it singles out the request speech act in the workplace context and scrutinizes how this speech act performed by 129 130 male superiors is actually constructed. To fill this gap in the current research, this study qualitatively explores how request discourse is constructed in superior-subordinate interactions in a Japanese workplace. In particular, the present study examines how male superiors utilize “supportive moves” in conjunction 1 with the Vroot +te kureru (Would you do X for me?) construction in order to actualize their requests (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989, p.17). A supportive move is a linguistic device that modifies the illocutionary force of the request, and thus helps the speaker to make the addressee perform the speaker’s request (Blum-Kulka et al. 1989, p.17). The Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) construction is a formulaic expression that is often used in the request speech act and that previous studies (e.g. Blum-Kulka 1987, 1989; Rinnert & Kobayashi 1999; Searle 1975; Weizman1989) term “conventional indirect requests.” Categorizations of supportive moves vary from scholar to scholar. In this study, supportive moves include (a) checking on availability (e.g. Are you busy?), (b) getting a precommitment (e.g. Will you do me a favor?), (c) providing reasons, justifications, etc., (d) asking about the feasibility of the addressee’s performing a request, and (e) apologizing for bothering the addressee. This list incorporates most of Takano’s (2005) supportive moves with several of those suggested by Blum-Kulka 2 et al. (1989). The research question that this study addresses is: How do male superiors in a workplace hierarchy make requests to their subordinates? The study concludes that myriad contextual dimensions, such as the domain of the subordinates’ work duties, superiors’ perception of uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) membership categorization, the request contents, and superiors’ imposition on subordinates have a powerful influence on the superiors’ use of supportive moves in the case of this study. Because it investigates only a single workplace with limited occurrences of request discourse, I consider this a preliminary study. 2. Theoretical Framework Much of the research on workplace discourse in Western scholarship (e.g. Holmes 2006; Holmes & Stubbe 2003; Mullany 2007) has adopted the framework of Community of Practice (henceforth, CofP). The popularity of CofP among scholars can be attributed to the way this framework allows researchers to observe practical similarities and differences within and across workplaces (Holmes & Meyerhoff 1999; Mullany 131 2007). Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (1998, p.490) define CofP as an “aggregate of people who come together around mutual engagement in some common endeavor.” They go on to state that “ways of doing things, ways of talking, beliefs, values, power relations—in short, practices— emerge in the course of their joint activity around that endeavor” (p.490). This concept of community is different from the traditional notion of community “because it is defined simultaneously by its membership and by the practice in which that membership engages” (p.490). Individuals acquire sociolinguistic competence by shaping and reshaping their styles through participation in multiple CofPs (Eckert & McConnellGinet 1999). The nature of the CofP is hence strongly associated with and influences individuals’ interactional styles and their ways of speaking. Only a small amount of research on Japanese workplace discourse (e.g. Backhaus 2010; Geyer 2010) adopts this framework; none of it examines request speech acts. Because the workplace culture differs from workplace to workplace, and the framework of CofP seems to be beneficial to researchers, this study adopts Cof P as a theoretical framework. 3. Previous Studies 3.1 Gendered use of request strategies in workplace discourse Examining workplace discourse from the perspective of the scholarship on language and gender, Sunaoshi (1994) identifies Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) as one of the Passive Power Strategies (PPS), a designation originally coined by Smith (1992). PPS are characterized as lacking overt directive morphology or as marking that the speaker is receiving a favor. Sunaoshi (1994, p.687) maintains that “the forms categorized as PPS have politer linguistic forms; use of these forms follows the stereotype of Japanese women’s speech.” In her study, male superiors infrequently employ linguistic forms categorized as PPS; instead, they predominantly use imperatives. Likewise, Takano (2005) finds that male superiors in his study most frequently use imperative forms (19 tokens, 15.6%), whereas they employ the Vroot+te kureru construction in only three tokens (2.5%) out of the total of 122 tokens. Furthermore, Takano (2005) shows that female professionals in managerial positions use nearly twice as many supportive moves as their male counterparts (women 42%; men 20%). He claims that female professionals’ use of supportive moves can be a good strategy that works 132 to constitute their gender-preferred indirect directives. Because both Sunaoshi (1994) and Takano (2005) focus on female professionals’ language practices in workplaces, they do not closely examine how male superiors utilize Vroot+te kureru and supportive moves in the sequence of interactions. Filling these gaps in their research is a driving force for this study. 3.2 Request speech acts in Japanese Many previous studies on request speech acts in Japanese have been carried out in the field of applied linguistics and interlanguage pragmatics (e.g. Mizuno 1996; Taguchi 2006). Only a handful of the research on this topic (e.g. Fukushima 1996; Kawanari 1993) has investigated how native speakers of Japanese make requests to other native speakers. Both Fukushima (1996) and Kawanari (1993) argue that the speaker’s imposition on the addressee is a relevant factor in the use of supportive moves. Kawanari (1993) discusses the idea that Japanese are sensitive about the notion of imposition, and hence have a strong desire not to impose on others. 3 Relating her study to politeness strategies (Brown & Levinson 1987), Fukushima (1996) quantitatively examines request strategies by Japanese university students in peer interactions in comparison to those by their British counterparts. She finds that as the level of the imposition on the addressee increases, the Japanese tend to use supportive moves more frequently. Fukushima (1996) also maintains that in Japanese society, positive politeness and direct requests are often used and permitted among in-group members of equal status so as to strengthen the bond of the members, whereas negative politeness is preferred among out-group members, because in such relationships social distance is of high importance. She further contends that the “ingroup/out-group distinction is reflected in language choice” although such a difference in language use is bound by the degree of imposition (Fukushima 1996, p.687). Although both Fukushima’s (1996) and Kawanari’s (1993) studies are insightful, their data are elicited from role plays; hence, they may provide different results from the data derived from spontaneously occurring interactions. In addition, because the subjects of this earlier research are university students, we still do not know how individuals exercise linguistic practices in workplace settings. Hence, this study deepens both Kawanari’s (1993) and Fukushima’s (1996) research by analyzing naturally occurring data derived from interactions in a workplace. 133 4. The Study 4.1 Research site and participants The research site for this study is a dental laboratory in the Tokyo area that manufactures dentistry products, such as dentures and crowns, with 59 workers in total (49 men and 10 women). The company consists of administration and three departments: general affairs, manufacturing, and sales. The individuals in authoritative positions are all male. Seven male superiors with managerial positions originally participated in this research; however, the data from only four superiors (Table 1) will be presented in this study. These four superiors have all worked for the company for over ten years. Except for Sato, they are all dental lab technicians, possessing governmental licenses to engage in making dentistry products. Table 1: The participants Name Sasaki Takebuchi Sato Nakata Title President General Manager Department Chief Section Head Department Age Administration Manufacturing Sales Manufacturing 64 41 45 33 4.2 The data The data for this study are derived from more than 30 hours of recordings collected for a two-month period. Recording began about two weeks after employees seemed accustomed to the researcher’s presence. The participants were asked to carry voice recorders around with them and audio-record face-to-face interactions with their subordinates. It was agreed that the researcher would turn on each of their recorders once each day, and then the participant would let it play until it automatically turned off. Because the recording started the moment voice-recorders were given to the participants in the morning and continued until they automatically stopped, the participants did not have to turn on the recorders every time they interacted with their subordinates. In the data sets derived from the recording, there were 27 tokens of the Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) construction; 12 tokens 134 emerged in cross-sex interactions, while 15 tokens emerged in same-sex interactions. These 27 tokens will be the subject of linguistic scrutiny in this study. 5. Analysis A request implies that a directive is interpreted by the addressee as a favor to the speaker; thus, its actualization is left to the addressee (Lakoff 2004). It is, however, regarded as a face-threatening act by its nature; the speaker employs certain strategies in order to minimize the force of the face threat (Brown & Levinson 1987). It is obvious that supportive moves delivered in such request contexts serve to minimize the face threat. In this study, regardless of the subordinates’ gender, the Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) construction is often employed when male superiors make requests. When used in such a context, Vroot+te kureru works to acknowledge the addressee’s negative face wants. Furthermore, in conjunction with this linguistic construction, supportive moves are employed to further mitigate the face threat. 5.1 Making requests to male subordinates In this community of practice (i.e. the workplace), when making requests to male subordinates, male superiors produce supportive moves not only when requests are considered to be beyond the domain of subordinates’ work duties, but also when requests are within the scope of subordinates’ work duties. Such interactional patterns tend to occur in interactions with subordinates who are in soto (out-group) relationships—12 out of 15 cases of request tokens are observed in such relationships, whereas no supportive moves are provided in uchi (ingroup) relationships. In this study, relationships between superiors and subordinates from the same department are considered to be uchi; relationships between those who are from different departments considered to be soto; and relationships with individuals from the administration are also identified as soto. There seem to be variations in the supportive moves that the male superiors deliver depending upon the degree of the association between the request content and the subordinates’ prescribed work duties. In what follows, I will first analyze the examples in which superiors’ requests are within the scope of the subordinates’ prescribed work duties. When the requests are linked to male subordinates’ work duties, 135 the male superiors produce a particular supportive move (providing a reason, in this case) in conjunction with the Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) construction. Excerpt 1 exemplifies this pattern of exchange. In this excerpt, a male superior from the manufacturing department (Takebuchi) makes a request to a male subordinate from the sales department (Amano) to change the deadline for a particular synthetic product. As a general procedure, salespersons who received orders from dentists fill out instructional slips with the dentists’ directions and hand them in to dental lab technicians in the manufacturing department. Following the instructional slips, lab technicians complete the products. Therefore, salespersons serve as mediators between dentists and lab technicians; it is among the salespersons’ responsibilities to negotiate deadlines for the production of the synthetic products with dentists and lab technicians. Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) appears in bold face throughout this study. (See Appendix for transcription conventions.) Excerpt 1 1 Takebuchi: ano: mokee ga, ‘Well: the model [that I am working on]’ 2 Amano: hai. ‘Yes.’ 3 Takebuchi: nooki (henkoo) maniawanai n da. ‘[The model I am working on] cannot meet the deadline.’ 4 Amano: hai. ‘Alright.’ 5 Takebuchi: are dake chotto henkoo shite kureru ↑ ‘Would you change the deadline for only that one a bit?’ 6 Amano:a. wakarimashita. ano nooki (boku) no hoo de ichioo 7 settee shita dake na n de. ‘Oh, I got it. [Actually,] I just tentatively set up that deadline.’ In lines 1 and 3, Takebuchi informs Amano of his situation of being incapable of meeting the deadline for a particular model. Here, Takebuchi’s utterance ends with n da. Aoki (1986) proposes that the nominalizer no/n factualizes its preceding phrase or sentence. Iwasaki (1985) contends that n da marks non-challengeability, so that the information is likely to be accepted by the addressee. In other words, Takebuchi gives the information to Amano as a non-challengeable 136 fact. This utterance plays a part as a supportive move (i.e. providing a reason) for his upcoming request in line 5. Notice that in line 5, Takebuchi utters the hedge are dake chotto (only that one a bit) before the request. Serving as a softening device, a hedge contributes to mitigating the inherent illocutionary force of a request (Holmes 1984). By delivering a supportive move and a hedge prior to his request, Takebuchi attenuates the impact of the face threat. Furthermore, what is remarkable in this excerpt is that, while Takebuchi’s request may be very costly to Amano because changing the deadline involves negotiation with the dentist, and thus, the degree of Takebuchi’s imposition on Amano is high, Takebuchi only conveys a single supportive move with the hedge. On the other hand, when requests are considered as falling completely outside the domain of subordinates’ work duties, male superiors give multiple supportive moves. Again, such phenomena are predominantly observed in soto (out-group) relationships. Holmes and Stubbe (2003) propose that demanding that the worker perform what goes beyond his or her prescribed duties or obligations requires reducing the impact of the directive. For this reason, supportive moves are essential devices for superiors to attenuate the illocutionary force of their requests and to make their requests more indirect. The following exchange depicts an instance in which a male superior makes a request, using several supportive moves and Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?). Excerpt 2 [Sasaki is the company president; Ohta is a non-titled male employee from the sales department.] 1 Sasaki: oota-kun, ‘Mr. Ohta.’ 2 Ohta: hai. ‘Yes.’ 3 Sasaki: onegai da kedo sa. koko no eegyoo no tsukue no tokoro ni aru ne: ‘I have a favor to ask you. Here, on the desks of the sales department.’ 4 Ohta: hai= ‘Yes.’ 5 Sasaki: =ano soo yuu hora a:: kairan ga aru jan. ‘Well, those, you know, uh:: there are circular memos [on the desks of the sales department].’ 6 Ohta: hai. 137 ‘Yes.’ 7 Sasaki: are o minna kara ikkai ano:: tamatteru yatsu o dasasete, ‘Those [circular memos], from everyone, once, well, collect them [circular memos] that everyone has kept, and,’ 8 Ohta: hai. ‘Yes.’ 9 Sasaki: sorede zenbu ore no tokoro e motte kite kureru ↑ ‘And would you bring them all to me?’ 10 Ohta: ha= ‘Yes.’ 11 Sasaki: =ano:: kyoo itsudemo ii kara. sorede issoo suru kara yo. ‘Well, anytime today is fine [with me]. And then, that will clear everything.’ 12 Ohta: hai. ‘Alright.’ In line 3, Sasaki inserts a supportive move, getting a precommitment, with onegai da kedo sa (I have a favor to ask you), and shows his acknowledgement that his subsequent utterances will impact Ohta’s negative face wants (Brown & Levinson 1987). Then in line 9, Sasaki makes a request to Ohta to collect all circular memos and bring them to Sasaki. Because Ohta’s defined duties as a salesperson are primarily to cultivate new clients and to receive orders from dentists, what Sasaki has asked for is considered outside of Ohta’s work duties. In line 11, cutting off Ohta’s response, Sasaki rushes to deliver a supplemental utterance, which indicates his flexibility about Ohta’s actualization of Sasaki’s request. Sasaki’s utterance (line 11) gives Ohta freedom in regard to when he complies with the request, and thus mitigates Sasaki’s imposition on Ohta. Notice that Sasaki subsequently gives a reason to justify his request, issoo suru kara yo (that will clear everything), using the particle yo. The particle yo represents the speaker’s stance of strong authority toward the addressee and hence, it does not evoke negotiation between the speaker and the addressee (Morita 2002). With the particle yo, this supportive move (i.e. providing a reason) of Sasaki’s request is delivered in an authoritative manner. In this excerpt, Sasaki exhibits his attempts to minimize the face threat toward Ohta through the use of Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) and several supportive moves, while simultaneously using the particle yo to demonstrate his authority. It is worth noting that Sasaki’s request of collecting and bringing circular memos to him is not so costly 138 to Ohta; however, as opposed to Takebuchi in Excerpt 1, Sasaki employs more than one supportive move in this exchange. In Excerpt 3, Sato from the sales department makes a request to Iwasaki from the manufacturing department. Excerpt 3 1 Sato: ano sa:: iwasaki-san, soko ni sa:: sagyoo hyoo ga aru no. wakaru ↑ ‘You know, Mr. Iwasaki, there is the work list [of the sales department] there. Do you see it?’ 2 Iwasaki: sagyoo hyoo. ‘The work list.’ 3 Sato: sagyoo hyoo. ‘The work list.’ 4 Iwasaki: kore desu ka ↑ ‘This is it?’ 5 Sato: un. warui kedo cho cho kashite kureru ↑ ‘Yeah, sorry, but a bit, a bit, would you hand it on to me?’ In line 1, using the nominalizer no, Sato provides the factual information (Aoki 1986) that serves as a justification for his upcoming request, and he seeks to check on the feasibility of Iwasaki’s carrying out the request by saying wakaru (Do you see it?). Sato’s utterances in line 1 hence function as supportive moves. Then in line 5, Sato delivers an apologetic remark, warui kedo (I am sorry, but), along with the hedge cho (the contracted form of chotto ‘a bit’) prior to the request. In this short segment, Sato delivers a variety of supportive moves (i.e. providing a reason, checking on the feasibility, and apologetic remark) previous to his request. Again in this exchange, Sato’s imposition on Iwasaki is not so high, because handing the work list to him is not costly to Iwasaki. Yet, by effectively inserting supportive moves with hedges, Sato mitigates the illocutionary force of the upcoming request. Excerpts 1–3 illustrate that building on superiors’ perception of the uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) distinction, the contents of their requests and the domain of subordinates’ work duties are interwoven in complex ways and prompt the superiors to employ supportive moves. What is noticeable in these excerpts is that the superiors’ imposition on subordinates may not be an essential parameter that influences the frequency of their use of supportive moves. I will discuss this point further in a later section. 139 5.2 Making requests to female subordinates In cross-sex interactions, 10 out of 12 instances are observed in uchi (in-group) relationships; supportive moves are inserted in these interactions regardless of the scope of subordinates’ work duties—two instances are realized when the request is within their work duties; one when it is beyond the work duties. In contrast, no supportive moves are produced in soto (out-group) relationships. Although instances observed in soto relationships are extremely limited (and hence, I cannot make a definite claim), the findings suggest that male superiors’ use of supportive moves is not related to their perception of uchi/soto in crosssex interactions as closely as it is in same-sex interactions. Rather, it appears to be associated with other factors, such as subordinates’ defined work duties, the superior’s imposition on the subordinate, and the request content, as seen in Excerpt 4. Excerpt 4 is an exchange between Sato (the sales department chief) and his female subordinate (Watabe) who engages in clerical work in the sales department. In Japanese society, female employees like Watabe are known as Office Ladies (OL). Ogasawara (1998, p. 27) defines an OL as “a woman working regularly in an office who engages in simple, repetitive, clerical work without any expert knowledge or management responsibility.” She further states that OLs are employed to work as assistants of men who are employed to be managers. In this exchange, without any supportive moves, Sato makes a request to Watabe that is identifiable as within the scope of her work duties. Excerpt 4 1 Watabe:kachoo ato wa shinakya naranai koto arimasu ↑ mada are 2 ba:( ). ‘Department chief, is there anything else we have to do? If there still is, ( ).’ 3 Sato: socchi wa ↑ = ‘How about your tasks?’ 4 Watabe: =moo ato de shimasu. ‘I will do them later.’ 5 Sato:soo shitara na:: kore sa: o chotto kiite kite kureru ↑ 6 pooseren de kore, jii-enu de yaru no ka: ‘If so, would you ask them [employees in the manufacture department] a bit about this [synthetic tooth] for me? Whether they will make this with porcelain or with GN (name of a material)’ 140 7 Watabe: hai. ‘Alright.’ 8 Sato: soretomo a:: ( ) de yaru no ka: ‘Or uh:: [they will make it] with ( ).’ In this segment, Sato makes a request to Watabe with the use of Vroot+te kureru in line 5. Sato’s request is not exactly what Watabe engages in on a daily basis, since Sato specifies the synthetic tooth by saying kore (this). However, it can be considered part of Watabe’s work duties according to Ogasawara’s (1998) description of OLs—OLs work as assistants of men. Notice that Sato produces the hedge chotto (a bit) prior to the request form in line 5. Nevertheless, no supportive moves are delivered. One may argue that Sato’s utterance in line 3 can be regarded as a supportive move (i.e. checking on availability). However, Sato does not initiate this utterance; rather, he delivers it in response to Watabe’s offer. Upon Watabe’s uptake in line 4, Sato deploys the request, initiating the utterance, soo shitara (if so), which implies that Sato originally did not have any intention to convey a request to Watabe. In other words, Sato’s request in line 5 stems from Watabe’s response. Thus, Sato’s utterance in line 3 should not be interpreted as a supportive move; rather, he is simply asking about Watabe’s current work situation at this point. Sato’s verbal behavior in this excerpt may be due to the association between his request content and Watabe’s work duties in relation to his imposition on her. Obviously, merely asking someone in the same company is not costly to Watabe, and hence, Sato’s imposition on her is low; furthermore, what Sato is asking for can be considered to fall under the domain of Watabe’s work duties. It may be due to these factors that Sato provides no supportive moves in this exchange. The following exchange is also between Sato and Watabe. However, this time Sato produces a supportive move when making a request that also falls under her prescribed work duties. Excerpt 5 1 Sato:(mita shika) kara de nakazawa-san no faibaa koa ga nanka 2 todoite nai n da kedo tte itteta kedo, kakunin shite kurenai 3 ka:tte= ‘It’s from (Mita dentist), and they said that Ms. Nakazawa’s fiber core [name of the material] has not arrived, so asked us to confirm it.’ 141 4 Watabe: 5 Sato: 6 Watabe: 7 Sato: 8 Watabe: =e: ↑ What? Mita-san, nakazawa tomie-san tte yuu faibaa koa= ‘Mita dentist. Fiber core that is for Ms. Nakazawa Tomie.’ =hai. Yes. chotto ja. shirabete kureru ↑ ‘Then, would you look into it a bit?’ hai. Yes. In lines 1−3, Sato explains the situation to Watabe, which becomes a reason for his upcoming request in line 7. Upon Watabe’s repair token in line 4, Sato subsequently rephrases what he said in line 1. Then in line 7, he makes a request to Watabe to check out the case. Again, this task is not what Watabe engages in every day, because it is for a specific person, Ms. Nakazawa Tomie. Nevertheless, it can be identified as falling under Watabe’s work duties, considering Ogasawara’s (1998) definition of OLs. Here, Sato provides the hedge chotto (a bit) prior to the request form so as to further attenuate the illocutionary force of his request. The difference between Excerpts 4 and 5 is in what Sato has requested of Watabe. In Excerpt 5, Sato’s request can be considered very costly, because it may take up Watabe’s time; hence, Sato’s imposition on Watabe in this excerpt is higher than it is in Excerpt 4. This may occasion Sato’s deployment of a supportive move in Excerpt 5. Excerpts 4 and 5 provide evidence that in cross-sex interactions, the uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) distinction may not be a crucial factor. Indeed, in the data analyzed in this study, male superiors deploy no supportive moves in soto relationships, when request contents are 4 under the scope of subordinates’ work duties with low imposition. On the other hand, there is an instance, presented in Excerpt 6, where a male superior provides a female subordinate who is an uchi member with supportive moves. This is the only such case observed in this study; the superior’s request falls outside the domain of the subordinate’s prescribed work duties. In Excerpt 6, Nakata is a section head from the manufacturing department, and Ishida is a female lab technician who manufactures synthetic teeth along with male technicians. 142 Excerpt 6 1 Nakata: gurasu nan bon yan no ↑ ‘How many of glass do you have to deal with?’ 2 Ishida: a. go hon desu. ‘Oh. Five of glass.’ 3 Nakata:n de kyoo kenma ga mata gojuu rokuju-ppon chikaku aru n 4 da. dakara moshi kono dankai de chotto tsumatte tara mata 5 chotto haitte yatte[kureru ↑ ‘And again, we have nearly 50 to 60 synthetic teeth to polish today. So, if they [other employees who are in charge of polishing synthetic teeth] are in trouble polishing them all, would you help them out again?’ 6 Ishida: [wakarimashita. ‘I got it.’ Nakata checks with Ishida on the feasibility of her performing his upcoming request, haitte yatte kureru (Would you help them out?) in line 5, by saying gurasu nan bon yan no (How many of glass do you have to deal with?) in line 1, and with this, he attempts to get Ishida involved in a requestive context (Pufahl Bax 1986). Then in lines 3− 4, he provides a justification for his upcoming request, kyoo kenma ga mata gojuu rokuju-ppon chikaku aru n da (Again, we have nearly 50 to 60 synthetic teeth to polish today). It should be noted that Nakata’s utterance here ends with n da where n/no marks a fact (Aoki 1986), and n da indicates non-challengeability (Iwasaki 1985). In other words, Nakata explains the situation to Ishida as a non-challengeable fact, which renders it difficult for Ishida to negotiate with Nakata over his request. Nevertheless, Nakata uses Vroot+te kureru (Would you do X for me?) so as to attenuate the imposition of his request on Ishida and concurrently asks Ishida a favor. As the interaction unfolds, Nakata has set up a negatively polite environment for a request. In particular, providing factual information or a reason functions as mitigating a directive (e.g. Holmes & Stubbe 2003; Jones 1992), because it implies that the speaker’s impingement on the addressee’s negative face needs is inevitable and that otherwise, the speaker would not normally threaten the addressee’s face needs (Brown & Levinson 1987). Effectively exploiting the pragmatic force of n da, Nakata indicates the unavoidability of impingement on Ishida’s negative face. Two factors may cause Nakata’s use of diverse supportive moves in addition to the Vroot+te kureru construction. First, Nakata’s 143 request is unrelated to Ishida’s work duties, because other employees are in charge of the task that Nakata requests of Ishida. Second, Nakata’s request may be very costly to Ishida (polishing numerous synthetic teeth can be very time consuming), and hence, his imposition on her is high. Because of these two factors, Nakata may use multiple supportive moves although he is making his request to an uchi (in-group) member. Excerpts 4–6 show different interactional patterns when male superiors are making requests to female subordinates. The intricate connection among the subordinates’ work duties, the content of the requests, and superiors’ imposition on subordinates seems to underlie such differences in interactional patterns in cross-sex interactions. 6. Discussion The data in this study provide evidence that in this community of practice, four parameters play a significant role in the male superiors’ use of supportive moves, namely (1) the uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) concept, (2) the scope of subordinates’ prescribed work duties, (3) the request content, and (4) the degree of imposition on the subordinate. Tables 2 and 3 below summarize the male superiors’ interactional patterns in same-sex interactions and cross-sex interactions, respectively. Table 2: The interactional patterns of request in same-sex interactions Male subordinates from different departments Total instances (15 tokens) Requests that are within subordinates’ work duties Requests that are outside of subordinates’ work duties 12 Supportive moves +Vroot+te kureru (2/12) Supportive moves + Vroot+te kureru (10/12) Male subordinates from the same departments 3 Vroot+te kureru only (1/3) Vroot+te kureru only (2/3) In interactions with male subordinates, the male superiors’ perception of the uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) distinction may lead the male superiors to generate different interactional patterns in request contexts. Regardless of the correlation between subordinates’ work duties and their requests’ content, male superiors produce supportive moves only when making requests to male subordinates who belong to different departments (soto members). The type of supportive moves that the male superiors deliver, however, differ in 144 accordance with such correlations; a wider variety of supportive moves is likely to be inserted when the request lies outside the subordinates’ prescribed work duties (Excerpts 2 and 3) than when the request is within the domain of the subordinates’ duties (Excerpt 1). Moreover, the degree of imposition on the addressee may not be as influential in male superiors’ use of supportive moves as the domain of subordinates’ work duties. Even when it is under the scope of his defined work duties, a request can be very costly to the subordinate. Yet in such situations, male superiors in this study provide only a single supportive move (Excerpt 1). On the other hand, they insert multiple supportive moves even when their imposition on subordinates is low (Excerpts 2 and 3). Fukushima (1996) points out that as the level of the imposition on the addressee increases, the Japanese insert supportive moves more frequently. However, the results of this study demonstrate the opposite phenomenon. It is uncertain what exactly prompts male superiors to perform such linguistic practices at this point. For male superiors in this workplace, what are defined as work duties may be absolute no matter how high their imposition on the addressee would be, which may lead them to use supportive moves infrequently. This is certainly something that needs to be investigated in the future. Table 3: The interactional patterns of request in cross-sex interactions Total instances (12 tokens) Requests that are within subordinates’ work duties Requests that are outside of subordinates’ work duties Female subordinates from different departments Female subordinates from the same departments 2 Vroot+te kureru only (2/2) 10 Vroot+te kureru only (7/10) Supportive moves + Vroot+te kureru (0/2) Supportive moves + Vroot+te kureru (2/10) Supportive moves + Vroot+te kureru (1/10) In interactions with female subordinates, on the other hand, the request content, the scope of subordinates’ work duties, and the association between these seem to be more crucial factors than the uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) distinction. The request content is further connected to the degree of imposition on the subordinate. When making requests that fall under the scope of subordinates’ work duties with low imposition on subordinates, male superiors deliver no supportive moves (Excerpt 4); conversely, when making such a request with high imposition, the superior inserts a supportive move (Excerpt 145 5). When the request is beyond the subordinate’s work duties and has high imposition, a male superior also delivers supportive moves (Excerpt 6). However, it should be noted that the data in cross-sex interactions are not well balanced—interactions in soto relationships and between lab technicians, as well as those in which the request falls outside subordinates’ work duties, are too few. This limits my analysis and prevents me from making generalizations based on linguistic phenomena in these interactions. Within the scope of this limited analysis, the results suggest that unlike in same-sex interactions, the superiors’ imposition on subordinates may be a crucial element for their use of supportive moves in cross-sex interactions. It is also important to be aware that this study examines the particular community of practice; hence, the findings in this study may not be compatible with individuals’ linguistic practices observed in other communities, and the generalizability of the outcomes of this study is limited. It is clear that I cannot make overarching claims that go beyond the particular data examined in this study. This certainly leads me to call for future research on the same topic. Examining male superiors’ linguistic practices in other communities of practice will allow us to make connections and create more solid and holistic portrayals of interactional patterns in request discourse in Japanese workplace settings. 7. Conclusion Expanding on the work of previous studies on workplace discourse and request speech acts (e.g. Fukushima 1996; Furo 1996; Kawanari 1993; Sunaoshi 1994; Takano 2005), this study examines how male superiors in an institutional hierarchy construct request discourse, with a focus on their use of supportive moves. The data have demonstrated that even in a workplace where power differentials are salient, the construction of request discourse is a complicated interactional process. The study illustrates that myriad contextual dimensions, including the domain of subordinates’ prescribed work duties, the contents of requests, superiors’ imposition on subordinates, and superiors’ perceptions of uchi (in-group)/soto (out-group) distinctions, are intricately interconnected with one another; it is the interaction of these dimensions that determines superiors’ use of supportive moves. As I discussed in the previous section, there are several limitations in this study. In particular, the data of this study are very limited. I 146 could not obtain enough and sufficiently similar data to make a direct comparison between interactions with male subordinates and those with female subordinates. In order to make the findings of this study more valid and reliable and to go beyond the frame of the preliminary study, I need to obtain more data from this community of practice and further scrutinize linguistic phenomena in this workplace. Nevertheless, the limited analysis of this study provides evidence that our actual linguistic practices in naturally occurring settings may differ from those performed in role plays, because there are discrepancies between the results of this study and those of previous research (Fukushima 1996; Kawanari 1993) regarding the speaker’s imposition on the addressee. Future research on this topic with naturally occurring data in different communities of practice is definitely called for. Such research will make further contributions not only to the study of speech acts but also to applied linguistics and interlanguage pragmatics. Notes 1. Vroot (Verb root) refers to “a meaningful unit which cannot be given further morphological analysis” (Tsujimura 1996, p.128). 2. Takano’s (2005, p.647) supportive moves include: (a) Grounder (mainly, reasons for the directive), (b) Preparator (mainly, asking about the feasibility of the act), (c) Imposition minimizer (minimizing the speaker’s imposition on the addressee; e.g. “Moo akiraka ni habuku to wakatteru mono wa kekkoo nan desu ga, hitori de handan shinai de kudasai” [It is fine to [skip] the part that we have decided to skip, but please do not make a decision yourself]), and (d) Apologetics (apologizing for bothering the addressee). On the other hand, Blum-Kulka et al. (1989, p.287–288) categorize supportive moves into two types, mitigating and aggravating, and further classify them into sub-categories. Mitigating supportive moves include: (a) Preparator, (b) Getting a precommitment, (c) Grounder, (d) Disarmer (the speaker’s attempt to eliminate any opposition that the hearer may raise; e.g. “I know you don’t like lending out your notes, but could you make an exception this time?”), (e) Promise of reward (e.g. “Could you give me a lift home? I’ll pitch in on some gas”), and (f) Imposition minimizer. Aggravating supportive moves include (a) Insult, (b) Threat, and (c) Moralizing. Takano’s Imposition minimizer is excluded in this study, because what Takano considers an Imposition minimizer seems to be equivocal, and it can be identified as an introductory remark for the upcoming request. Hence, it is difficult to determine whether or not an utterance actually serves as an Imposition minimizer. Along the same line of reasoning, Blum-Kulka et al.’s (1989) Disarmer, Promise of reward, and Imposition minimizer are excluded, because these linguistic devices become quite similar to Grounders when translated into Japanese. In addition, Blum-Kulka et al.’s (1989) aggravating supportive moves are also excluded, as these 147 linguistic devices were not found in the data analyzed in this study. 3. Identifying politeness as intentional strategic behaviors that the Model Person draws on in order to minimize his or her threat to the hearer’s or his/her own face when performing a face-threatening act, Brown and Levinson (1987) suggest five possible strategies, including positive and negative politeness strategies. Positive politeness is approach-based and oriented to the positive face of an interlocutor; it is thus used to express intimacy, common ground, and shared wants. Negative politeness is, on the other hand, based on avoidance and attends to an interlocutor’s negative face. The speaker attempts to avoid impeding the interlocutor’s freedom of action through acknowledgement of his or her negative face wants. Positive face represents the desire to be approved of and appreciated by others, while negative face relates to the desire to be unimpeded by others. 4. Due to space limitation, I will not present examples of this type of instance. Also, I did not observe any cases in which superiors make requests to female employees who are in soto (out-group) relationships that lie outside their work duties. References Aoki, Haruo. 1986. “Evidentials in Japanese.” In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Eds. by Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood: Ablex, 223–238. Backhaus, Peter. 2010. “Time to get up: Compliance-gaining in a Japanese eldercare facility.” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 20: 69–89. Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1987. “Indirectness and politeness in requests: Same or different?” Journal of Pragmatics, 11: 131–146. Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1989. “Playing it safe: The role of conventionality in indirectness.” In Cross-Cultural Pragmatics: Requests and Apologies. Eds. by Shoshana Blum-Kulka, Juliane House, and Gabriele Kasper. Norwood: Ablex, 37–70. Blum-Kulka, Shoshana, Juliane House, and Gabriele Kasper eds. 1989. CrossCultural Pragmatics: Requests and Apologies. Norwood: Ablex. Brown, Penelope and Stephen Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eckert, Penelope and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 1998. “Community of practice: Where language, gender, and power all live.” In Language and Gender: A Reader. Ed. by Jennifer Coates. Malden: Blackwell, 484–494. Eckert, Penelope and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 1999. “New generalizations and explanations in language and gender research.” Language in Society, 28: 185–201. Fukushima, Saeko. 1996. “Request strategies in British English and Japanese.” Language Sciences, 18: 671–688. Furo, Hiroko. 1996. “Linguistic conflict of Japanese women: Is that a 148 request or an order?” In Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Women and Language Conference. Eds. by Natasha Warner, Jocelyn Ahlers, Leela Bilmes, Monica Oliver, Suzanne Wertheim, and Melinda Chen. Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group, 247–259. Geyer, Naomi. 2010. “Teasing and ambivalent face in Japanese multi-party discourse.” Journal of Pragmatics, 42: 2120–2130. Holmes, Janet. 1984. “Modifying illocutionary force.” Journal of Pragmatics, 8: 345–365. Holmes, Janet. 2006. Gendered Talk at Work: Constructing Gender Identity through Workplace Discourse. Malden: Blackwell. Holmes, Janet and Miriam Meyerhoff. 1999. “The community of practice: Theories and methodologies in language and gender research.” Language in Society, 28: 173–183. Holmes, Janet and Maria Stubbe. 2003. Power and Politeness in the Workplace: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Talk at Work. London: Longman. Iwasaki, Shoichi. 1985. “Cohesion, nonchallengeability, and the –n desu clause in Japanese spoken discourse.” Journal of Asian Culture, 9: 125–142. Jones, Kimberly. 1992. “A question of context: Directive use at a Morris team meeting.” Language in Society, 21: 427–445. Kawanari, Mika. 1993. “Irai hyoogen [Request expressions].” Nihongogaku, 12: 125–134. Lakoff, Robin. 2004. “Language and women’s place.” In Language and Women’s Place: Text and Commentaries. Ed. by Mary Bucholtz. New York: Oxford University Press, 39–102. Mizuno, Kahoru. 1996. “Irai no gengo koodoo ni okeru chuukangengogoyooron : Directness to perspective no kanten kara [Interlanguage pragmatics in linguistic behaviors of requests: From the viewpoint of directness and perspective].” Gengobunka ron shuu, 18: 57–72. Morita, Emi. 2002. “Stance marking in the collaborative completion of sentences: Final particles as epistemic markers in Japanese.” In Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 10. Eds. by Noriko Akatsuka and Susan Strauss. Stanford: CSLI, 220–234. Mullany, Louise. 2007. Gendered Discourse in the Professional Workplace. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Ogasawara, Yoko. 1998. Office Ladies and Salaried Men: Power, Gender, and Work in Japanese Companies. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press. Pufahl Bax, Ingrid. 1986. “How to assign work in an office: A comparison of spoken and written directives in American English.” Journal of Pragmatics, 10: 673–692. 149 Rinnert, Carol and Hiroe Kobayashi. 1999. “Requestive hints in Japanese and English.” Journal of Pragmatics, 31: 1173–1201. Searle, John R. 1975. “Indirect speech acts.” In Syntax and Semantics: Vol. 3: Speech Acts. Eds. by Peter Cole and Jerry L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press, 59–82. Smith, Janet. 1992. “Women in charge: Politeness and directives in the speech of Japanese women.” Language in Society, 21: 59–82. Sunaoshi, Yukako. 1994. “Mild directives work effectively: Japanese women in command.” In Cultural Performances: Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Women and Language Conference. Eds. by Mary Bucholtz, Anita C. Liang, Laurel A. Sutton, and Caitlin Hines. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, 678–690. Taguchi, Naoko. 2006. “Analysis of appropriateness in a speech act of request in L2 English.” Pragmatics, 16: 513–533. Takano, Shoji. 2005. “Re-examining linguistic power: Strategic uses of directives by professional Japanese women in positions of authority and leadership.” Journal of Pragmatics, 37: 633–666. Tsujimura, Natsuko. 1996. An Introduction to Japanese Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. Weizman, Elda. 1989. “Requestive hints.” In Cross-Cultural Pragmatics: Requests and Apologies. Eds. by Shoshana Blum-Kulka, Juliane House, and Gabriele Kasper. Norwood: Ablex, 71–95. Appendix: Transcription conventions [ The point of overlap onset = Latching (0.0) Elapsed time in silence by tenths of seconds (.) Micro pause word Some form of stress (voice amplitude) :Prolongation of the immediately prior sound; multiple colons indicate a more prolonged sound A rising intonation ↑ . A falling intonation , A continuing intonation ( ) The transcriber’s inability to hear what was said (word)The transcriber’s best guess of what was said, but the accuracy is not assured