1 Intergenerational Justice, Extended Families, and the Challenge of

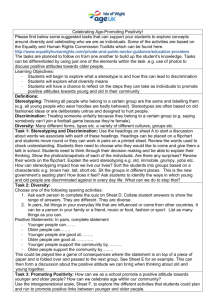

advertisement

Dr 120413 Rough Prelim Dr - Ext Fams Intergenerational Justice, Extended Families, and the Challenge of the Statist Paradigm by Professor Lynn D. Wardle 1 I. Introduction to the Link Between Extended Families and Intergenerational Justice Intergenerational justice has become one of the driving concerns of this first quarter of the 21st century. 2 Awareness of the finite limits of our world and its resources, the interconnections between demographic generations, and consideration of the duties of one 1 Bruce C. Hafen Professor of Law at J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA. I acknowledge the valuable research assistance of Swati Sharma and Jennifer Rajan. This paper originally was prepared for and presented at the Symposium on the Jurisprudence of Extended Families, Extending Families, and Intergenerational Solidarity, April 30-May1, 2012 in Doha, Qatar, cosponsored by the International Academy for the Study of the Jurisprudence of the Family, and by the gracious hosting institution, the Doha International Institute for Family Studies and Development. 2 See generally Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations, at Themes, #1, available at http://www.intergenerationaljustice.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=95&Itemid=125 (seen 19 January 2012) (“ ‘Generational justic’ is well on its way to becoming the driving issue for the next centuries. In view of the dramatic changes in the demographic composition of many developed countries, questions concerning the justice between the older, younger, and future generations will be as important as the highly debated questions of social justice (the justice between the rich and the poor). The call for new ethics that consider the rights of coming generations is urgent as we learn about and take responsibility for the far-reaching consequences of human actions.”); id. at ##1-10 (identifying ten dimensions of intergenerational justice). See also D__ Foot & R__ Venne, Awakening to the Intergenerational Equity Debate in Canada in __ Journal of Canadian Studies __ (2005) *√ (“Intergenerational equity in economic, psychological, and sociological contexts, is the concept or idea of fairness or justice in relationships between children, youth, adults and seniors, particularly in terms of treatment and interactions. It has been studied in environmental and sociological settings.”) Keith Aoki, Food Forethought: Intergenerational Equity and Global Food Supply – Past, Present and Future, 2011 Wis. L. Rev. 399, 403 (2011). √ (Intergenerational equity is the “concept that our contemporary society has a relationships with both past and future generations and raises the question of how these relationships should influence our decision-making today.”) Scholars have discussed intergenerational equity as it relates to natural resources, property law, agricultural law, environmental law, and education law. See, e.g., Edith Brown Weiss, Intergenerational Equity: Toward an International Legal Framework, in Global Accord: Environmental Challenges and International Responses 333 (Nazli Choucri ed., 1993). √ See generally Karen Glsaser et al, Family Disruptiosn and Social Support Among Older People Across Europe, Seminar on Family Support Networks and Populations Aging, Doha, Qatar, 3-4 June 2009 (3 June 2009) (growing issues of family support due to aging and family disruption) (copy in author’s possession). 1 generation to succeeding generations have become topics of major concern around the world. 3 Issues of distributive justice between adults and children, between the old and the young, between past, present and future generations are receiving significant attention from policy makers and scholars in many cultures, societies, nations and international organizations. 4 The core of the subject is recognition of apparently conflicting claims to limited resources. 5 “[P]utting intragenerational equity into practice can generate enormous political conflict, particularly along North-South lines.” 6 Because “change [of] consumptions patterns” and adoption of the contentious concept of sustainable consumption have been persistent 3 See Richard B. Howarth, Intergenerational Justice and the Chain of Obligation , 1 Environmental Values. 133 (1992) (arguing that the present generation must ensure conditions favorable to the welfare of future generations, because if their welfare is not ensured, our children’s generation not be able to fulfill their obligation to their children -- although they may be able to enjoy the benefits we reap for them.); M.L.J. Wissenburg, Parenting and Intergenerational Justice: Why Collective Obligations Towards Future Generations Take Second Place to Individual Responsibility , 24 Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 557-573 (2011) (prioritizing individual interest in responsibility for future generations will have greater benefit that general collective intergenerational duties); Richard P. Hiskes, The Right to a Green Future: Human Rights, Environmentalism, and Intergenerational Justice, 27 Human Rights Quarterly. 1346 (2005) (right to enjoy a safe environment linked to concern for the future). 4 See generally NEIL CARTER, UNDERSTANDING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (Cambridge University Press, 2005), available at http://www.fathom.com/course/21701763/index.html (seen 12 April 2012); PETER LASLETT & JAMES FISHKIN, JUSTICE BETWEEN AGE GROUPS AND GENERATIONS (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992); E_. BROWN-WEISS, (1989) IN FAIRNESS TO FUTURE GENERATIONS: INTERNATIONAL LAW, COMMON PATRIMONY AND INTERGENERATIONAL EQUITY (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Transitional Publishers, Inc., 1989) (for the United Nations University, Tokyo); Seymour Moskowitz, Adult Children and Indigent Parents: Intergenerational Responsibilities in International Perspective, 86 MARQ. L. REV. 401 (2002); B_ Frischmann, Some Thoughts on Shortsightedness and Intergenerational Equity, 36 Loyola University Chicago Law Journal __ (2005); Howarth, R. & Norgaard, R.B. Intergenerational Resource Rights, Efficiency, and Social Optimality, 66(1) Land Economics 1, 1-11 (1990); R.I. Sikora, & B. Barry, OBLIGATIONS TO FUTURE GENERATIONS (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. 1978). See also Intergenerational Justice in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice-intergenerational/ on intergenerational justice (seen January 9, 2012). √ 5 “The tension between economic growth and environmental protection lies at the heart of environmental politics. The concept of sustainable development is a direct attempt to resolve this dichotomy by sending out the message that it is possible to have economic development while also protecting the environment.” Carter, supra note __, at __ (Seminar Introduction). “[The Brundtland Report] concluded that sustainable development is impossible while poverty and massive social injustices persist; hence the importance attributed to intragenerational equity alongside the more straightforwardly environmental principle of intergenerational equity.” Id. at __ (Session 2, Core Principles of Sustainable Development) 6 Carter, supra note __, at __ (Session 2, Core Principles of Sustainable Development). 2 recommendation for efforts to achieve intergenerational equity, the concept of intergenerational justice remains as divisive as it is inescapable. 7 The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, I will make the case that the role of extended families holds the key to (or at least are an indispensable part of) the success or failure of efforts to achieve intergenerational justice. I will also argue, conversely, that the attempt to radically redefine families to give legal status to other relationships based on romance or affection such as legalizing same-sex marriage and treating same-sex partners as parents in the law is contrary to and dangerous for the goal of intergenerational justice. Second, I will suggest that statism is part of the problem that impairs recognition of and respect for extended families and that impedes intergenerational justice. I will argue that there is a serious jurisprudential conflict between two competing conceptions of human nature, and two competing power-center institutions for regulate humans. II. The Critical Role Extended Families in Intergenerational Justice The critical role of families has been largely neglected in the intergenerational justice dialogue. The impact of family structure upon intergenerational justice has been largely overlooked. While public programs, initiatives and influences upon intergenerational equity have been the focus of the debate, perhaps the key to the solution to the issue is to recognize, respect and enhances the importance of private influences. Especially families, family systems and family structures have great influences upon the existence of protections for, and transfers and deferrals from one generation for, the benefit of other generations. In short, some family 7 Id. For examples of inter-generational conflicts fostered by these dynamics, see generally Philippe V. Parijs, The Disfranchisement of the Elderly and Other Attempts to Secure Intergenerational Justice, 27 Philosophy & Public Affairs 292 (1998) (proposing that the elderly lose their voting rights at age 70, or retirement, which ever comes first); 3 structures and systems enhance and encourage intergenerational connections, commitments, transfers, sacrifices and efficiencies; while other family structures, systems and practices are contrary to, opposed to, minimize and weaken intergenerational equity. One reason why the importance of private families, family structures and family systems has been overlooked is because of who is doing the looking. Most of the research, debate, discussion, and proposing has been sponsored, promoted, and led by state government organizations – state-funded, state-licensed, state-approved, state-authorized agencies and officials. An old adage says that he who pays the piper calls the tune, and without any intentional effort to censor or bias the research, state actors generally have an inherent bias in favor of state action, activities, programs and institutions. Thus, it is not surprising that government agencies, government universities, government programs, and government-funded research focus on and primarily promote government remedies. This bias in favor of public, government, state-controlled solutions is called statism. The contrasting approach that favors private, family-controlled, non-governmental solutions is called familism. (For purposes of this paper, I will included individualism as a sub-set of familism as families exist to prepare and liberate private individuals from the control of the state and its public agencies, regulations, and programs.) Extended families provide a sense of connection, continuity, belonging and place that are critical human needs. As Professor Rèmi Brague has eloquently explained, nurturing such natural, familial connections is essential to social cohesion and development. 8 Extended families generally (when not rigid or authoritarian) enlarge and deepen kinship identity providing children, youth and mature adults with relational groundings, root paradigms, and foster trust in 8 Professor Rèmi Brague, “A New Nobility: The Family,” October 21, 2011, at Brigham Young University. √ # * 4 others and in the future, as noted by Dr. Merlin Myers. That nurturing of trust by extended families and familism undergirds the well-being of rising generations by facilitating the building of social capital and natural justice. Recognition of extended families promotes intergenerational justice. Extended families manifest a form of natural justice. That is, they are natural, exist in nature, in the natural world, are internally formed and based and valid; they are not artificial; they do not depend upon external sources for creation or existence or perpetuation. Extended families have functioned for millennia as valuable support systems for nuclear families, especially to safeguard and benefit children. The United States is a very individualistic society and is quite affluent, 9 and that is a major reason why legal recognition of the extended family as the primary family form was replaced by the nuclear family as the dominant and preferred family form many decades ago. “[L]iberty and the pursuit of [h]appiness” have been considered fundamental and inalienable human rights since the Declaration of Independence in 1776 in the United States, 10 and globally since at least the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognition of each human being’s “right to life, liberty and security of person” has been one of the guiding, core, indefeasible basic principle of global human rights. 11 As Japanese legal scholar Akira Morita put it: “Modern Western society has tended to view human dependency as tantamount to subordination, or even as a sign of inferiority.”12 “The American people [especially] are well 9 See, e.g., Bruce C. Hafen, Individualism and Autonomy in Family Law: The Waning of Belonging, 1991 BYU L. Rev. 1 (1991). 10 Declaration of Independence (1776). 11 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 3 (1948). 12 Akira Morita, On the Concept of Human Rights—A Cross-Cultural Reconsideration at 4 (Feldkirch, Aug. 31, 2002) (on file with author). 5 known for stressing the role of individual rights within society.” 13 As far back as 1831 Alexis de Tocqueville noted that individual “sovereignty” (i.e., individual liberty) was the “fundamental principle” and “the grand maxim upon which civil and political society rests in the United States.” 14 Professor Carl Schneider has noted that “[p]erhaps no idea in American life has become so convincing as the belief that each of us is entitled to live autonomously.” 15 He added: “Americans ‘abhor[] . . . dependence,’ to the point that they even ‘fear ties that bind’” 16 So the waning in America of the binding and commitments of extended family living, which curtail individual autonomy is not surprising. Yet in a major Supreme Court decision, in Moore v. City of East Cleveland, Justice Lewis Powell of the Supreme Court of the United States eloquently lauded the importance of extended families in American society. In that case, the Court overturned the conviction of a grandmother who had been fined for violating a city housing code that forbade grandchildren from two different children of hers to live with her. Justice Powell declared: Ours is by no means a tradition limited to respect for the bonds uniting the members of the nuclear family. The tradition of uncles, aunts, cousins, and especially grandparents sharing a household along with parents and children has roots equally venerable and equally deserving of constitutional recognition. . . . Even if conditions of modern society have brought about a decline in extended family households, they have not erased the accumulated wisdom of civilization, 13 Tatsuo Inoue, The Poverty of Rights-Blind Communality: Looking Through the Window of Japan, 1993 B.Y.U. L. Rev. 517, 518 (1993). 14 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America 418 (Phillips Bradley ed., Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1953) (1835). See generally Lynn D. Wardle, Parenthood and the Limits of Adult Autonomy, 24 St. L. U. Pub. L. Rev. 169 (2005). 15 Carl E. Schneider, Fixing the Family: Legal Acts and Cultural Admonitions, in Revitalizing the Institution of Marriage for the Twenty-First Century: An Agenda for Strengthening Marriage 181 (Alan J. Hawkins et al. eds., 2002). 16 Schneider, Fixing the Family, supra, at 181. 6 gained over the centuries and honored throughout our history, that supports a larger conception of the family. Out of choice, necessity, or a sense of family responsibility, it has been common for close relatives to draw together and participate in the duties and the satisfactions of a common home. 17 He also added: “Decisions concerning child rearing, which Yoder, Meyer, Pierce and other cases have recognized as entitled to constitutional protection, long have been shared with grandparents or other relatives who occupy the same household indeed who may take on major responsibility for the rearing of the children.” 18 In the same case, Justice Brennan (concurring) agreed: The “extended family” that provided generations of early Americans with social services and economic and emotional support in times of hardship, and was the beachhead for successive waves of immigrants who populated our cities, remains not merely still a pervasive living pattern, but under the goad of brutal economic necessity, a prominent pattern virtually a means of survival for large numbers of the poor and deprived minorities of our society. For them compelled pooling of scant resources requires compelled sharing of a household. 19 Similar judicial tributes to the importance of the extended family in America have been repeated not infrequently by the Supreme Court. 20 Thus, even in what may be the most individualistic, nuclear-family-oriented nation on earth the constitutional tradition 17 Moore, 431 U.S. at 504-05. Id.. Moore, 431 U.S. at 504-05. Id.. 19 Id. at 508 (Brennan, J., concurring) (emphasis added). Id. at 509 (“We may suppose that this reflects the truism that black citizens, like generations of white immigrants before them, have been victims of economic and other disadvantages that would worsen if they were compelled to abandon extended, for nuclear, living patterns.”). 20 See, e.g., *; *; *. 18 7 of recognition of the critical importance of extended families continues acknowledging that extended families extend a great amount of private aid and private support, especially in times of trial, hardship, distress, economic suffering and emergency situations. Note that what is recognized is voluntary adoption of extended family living and support, protecting the option of adopting and embracing some form or extended family, not mandatory or compulsory submission to extended family legal regimes. Times of crisis tend to turn the hearts of the different generations and extended families towards each other for mutual support. Especially in times of financial distress, war, natural disasters, economic depressions (personal, regional or global) and other crises, extended families have great importance as potential sources of material and interpersonal support and of providing basic familial services (including education, socialization, preparation and capitalization). The critical importance of sociological role of extended families (apart from their economic back-stopping function) was suggested 2500 years ago by the Old Testament prophet Malachi. His sober counsel, given in the last verse of the Old Testament, spoke of the return of the prophet Elijah before some “great and dreadful day of the Lord: And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to the fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse.” 21 Similar teachings can be found in many other great world religions. For example, the Qu=ran teaches that children are a bounty (gift) from Allah .16 A famous "hadith" (the sayings of 21 Malachi 4:5, 6. Holy Qur=an (Al A=raf), at 7:190, at <http://www.alislam.org/quran/translation/7.html>, (last visited on Sep. 11, 2003); see also Kathleen A. Portuán Miller, The Other Side of the Coin: A Look at Islamic Law As Compared to Anglo-American Law B Do Muslim Women Really Have Fewer Rights Than American Women?, 16 N.Y. Int'l L. Rev. 65, 103 (2003). .16 8 Mohammed and his companions), states: "Paradise lies at the feet of mothers. "17 The Prophet taught that husbands have the duty to support their families, and that women nurturing young children are entitled to special support, and that a father=s salvation and exaltation in heaven depends on his providing properly for and patiently teaching his children. 22 We can expect times of crisis to increase for families in the coming years, and thus the need for extended families to increase. For example, births are below replacement level in scores of nations. In some nations births are down to about one-half the replacement level of 2.1 births per couple) in all nations of Eastern Europe except one (Albania). 23 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports that none of the nations of Europe can maintain their population (necessary for economic sustainability) through births, that only France, (with a birth rate of 1.8) has the possibility to do so; and the fall in fertility in Eastern Europe has been Aprecipitous.@ 24 In fifteen European nations the rate of fertility is 1.3 or below, and a birthrate of 1.4 or 1.5 means that the population will decrease by one-third each generation. 25 "17 Miller, supra note __, at 103 (citing B. Aisha Lemu, Woman in Islam 239 (1992)); Shaikha Kouthar Allie Cader, Family Life in Islam/ Women in Islam at 4, paper delivered at the World Family Policy Forum, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, July 14, 2003 (copy in author=s possession) (attributing this saying to the Prophet). Id. at 103-104: "[T]he Holy Qur'an . . . says, >Sacred are family relationships that arise through marriage and women bearing children.= Motherhood and children are highly valued in the Islamic culture." "Mohammed said: >He whosever has three daughters and exercises patience with them, feeds them, clothes them according to his own income, will ... be protected from the hellfire (will have a place in heaven).=" Id. at 104. See also Understanding Islam and the Muslims, Question 22 <http://islamicweb.com/begin/understanding?islam.htm#Q22 (Seen Sept. 15, 2002). 22 See generally id. at __; √ ** 23 Id. European Birth Rates Reach Historic Low, supra, note __, at __. The crude birth rate in 10 of the fifteen nations of Eastern Europe in 2000 was 10.0 or below, and between 1990 and 2001, that birth rate dropped profoundly (in some cases nearly in half) all fifteen nations. Id., Crude Birth Rates, at http://www.k-state.edu/sasw/kpc/eedemo/resources-birth.htm (Seen October 3, 2006). 24 European Birth Rates Reach Historic Low in Part Because of Recent Fall in Eastern Europe, Sept. 8, 2006, available at http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=51329 (seen October 3, 2006). Id. (In 1990 no European country had a birth rate below 1.3; but in 2002 fifteen European nations had birth rates below 1.3). 25 See Weigel, supra note 22, n.*. 9 A similar revolution in birth rate and family size is also occurring in the Islamic world. As Dr. Nicholas Eberstadt has reported in The Islamic world’s quiet revolution, “According to the UN's Population Division, all Muslim-majority countries and territories witnessed fertility declines over the past three decades.” 26 Indeed, as Table 1 below shows, “six of the ten largest declines in fertility in absolute terms for a 20-year decade period in the postwar era have occurred in Muslim-majority countries. What's more, four of the six are Arab countries, while five of the six are in the Middle East. No other region of the world comes close in the sheer speed of its transition.” 27 Of course, fertility rates vary dramatically among Muslim countries and populations, as they do in Western and other groupings of nations, but the striking fact is that the fertility rate in 26 Nicholas Eberstadt, The Islamic world’s quiet revolution, American Enterprise Institution (AEI), Global Health (March 12, 2012), available at file:///C:/wardle/Publications/Articles&Chs/1204%20Doha%20Ext%20Fam/RES%20art%20The%20Islamic%20world%27s%20quiet%20revolution%20-%20Health%20-%20AEI.htm (seen 15 March 2012). Dr. Eberstadt holds “the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). He is also Senior Advisor to t he National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR), [and] a member of the visiting committee at the Harvard School of Public Health . . . .” Nicholas Eberstadt, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Eberstadt (seen 12 April 2012). 27 Id, quiet revolution, at __. 10 some Islamic socities is comparable to the fertility rates in many American states, as Dr. Eberstadt’s chart below indicates. Interestingly, while education, urganization, income, public health conditions, and treatment or women have been associated with fertility, Dr. Eberstadt endorsed the conclusion of Harvard Economist Lant Pritchett that “the desired fertility . . . was the single best predictor for actual fertility levels in less developed regions” accounting for “90 percent of the statistical variance . . . .” 28 This “hidden-in-plain sight revolution” is such a surprise indicates that most scholars, especially westerners, really do not understand “the societies beneath” the political images of so many Muslim nations. 29 Similarly, that we academics have been taken by surprise by the dramatic “demographic winter” that is occurring in so many western nations suggests that we may not understand our own societies, either. Due to low fertility rates, a Ademographic winter@ is descending upon Europe. British historian Niall Ferguson calls this imminent demographic change Athe greatest >sustained reduction in European population since the Black Death of the 14th Century.@ 30 For example, Germany is poised Ato lose the equivalent of the population of the former East 28 29 Id. Id. 30 George Weigel, The Cube and the Cathedral 21 (2005), citing Niall Ferguson, Eurabia?, N.Y. Times Magazine, April 4, 2004. 11 Germany in the first half of the 21st century,@ and by 2050 it is estimated that 60% of Italians living will have no brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts or uncles. 31 Just when extended families may be needed the most, extended families are diminishing and disappearing in the West. Falling fertility rates facilitate the move to a nuclear family model of society. But they also increase the prospects for economic hardship and deprivation as sustainable development and economic growth require at least replacement levels of fertility. So the need for the safety net of extended families is likely to increase due to the economic development effects of dramatically-falling birth rates in so many nations. Children and adults grow in competence and self-confidence as they perceive their connectedness with ancestors as well as posterity, with collateral relatives as well as their own nuclear family. Let me give a personal example. Our youngest son and his wife and four children live about 1600 miles (c. 2400 km) away from where my wife and I life. Their other grandparents also live hundreds of miles from them. So they do not have any relatives living close to them. Two years ago, my extended family had a big reunion attended by nearly 300 persons related to each other. After a few minutes of being around so many relatives, my oldest grandson, then eight years old, came running up to me and said: “Grandpa, I didn’t know that Wardles were so important! Just being around a significant number of relatives gave him a sense of identity, place and significance that increased his self-esteem. That is what extended families can and should do, and one of the reasons why they can be so beneficial and are so important. Of course, extended families can be oppressive and stifling. The rigid Ie extended family system in pre-World-War-II Japan distorted that society, stifled many individuals, especially 31 Weigel, supra note __, at 22. See also European Birth Rates Reach Historic Law in Part Because of Recent Fall in Eastern Europe, Sept. 8, 2006, available at http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=51329 (seen October 3, 2006). 12 women, limited opportunities, nurtured autocratic attitudes, and was deemed to be responsible in part for the militarism that led to Japanese aggression in World War II. So the Allies, after defeating Japan in the war, insisted that the new Constitution of Japan outlaw and abolish the ie system, which it did. So it is not the label “extended family” but the substance of the sacrificial, caring systems that determines the potential value, or harm, of the extended family. ** III. Extending “Family” Status to Other Kinds of Intimate Relationships In contrast to respecting and making room in our social and legal systems for extended families, extending (redefining) family status to other forms of intimate and romantic attachments promotes an ego-individualistic, statist paradigm which exalts the self and undermines intergenerational justice. Recognition of same-sex marriage and same-sex partners as “parents” undermines natural family relations and weakens the ties of kinship in extended families. The movement to legalize same-sex marriage and parenting by same-sex couples can be seen as an attempt to fundamentally redefine the root paradigm of parenthood. Legalization of adoption by same-sex couples would radically alter the nature of the root paradigm of marriage, parenthood, and family. Cultural anthropologists use the concept of "root paradigms" to explain how society prepares and guides its members to cope with crises of personal, familial and social identity.32 All societies provide their members with root paradigms that "reflect the assumptions underlying 32 See Merlin G. Myers, The Morality of Kinship, the Virginia F. Cutler Lecture, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, November 15, 1983, in BYU Speeches of the Year, 1983-84 (hereinafter cited as "Myers"). See generally Lynn D. Wardle, Parenthood and the Limits of Adult Autonomy, 24 ST. L. U. PUB. L. REV. 169 (2005). 13 the very nature of existence. . . . They guide behavior of both individuals and groups in the crises of life and often require self-sacrifice on the part of individuals in the interest of group welfare. "33 Root paradigms "are, at the socio-cultural level analogous to DNA and RNA at the genetic level.” 34 They crystallize the formative validity beliefs of society. The renowned BYU cultural anthropologist, Professor Merlin G. Myers, reported that “relationships can be ranked on a continuum on the basis of their moral content.” 35 He noted that “sacrifice is the ready index to the moral quality of a relationship. If one is willing to sacrifice only a little, morality is small; if much, morality is great. . . .” 36 Thus, "[i[n a purely technical means-to-end relationship, the failure of the means to achieve the desired end results . . .[results] in a change of means. . . .[S]ome . . . human social relationships are like this. When there is delay or inbalance in the reciprocal aspects of the relationship, it may be terminated. (People are then being dealt with as if they were things.) However, in other kinds of relationships, neither delay nor inbalance terminates the association. . . . [I]t is morality that makes the difference. The demand for an immediate, or for a strictly equivalent, return for services or presentations given is tantamount to a denial of any moral relationship between the parties, while the presence of delay and imbalance between gift and counter-gift is synonymous with the presence of morality 37. Dr. Myers also noted that “[t]he domain of kinship predicates a kind of morality characterized by kindness and a predisposition to love and care . . . . The root words, kindness, kind and the 33 Id. at 45. Id. 35 Id. at __.√ 36 Id. at __.√ 37 Id. at 50. 34 14 German word for child, kind, all have the same generic root, and all express the moral character of kinship. Kinsmen are expected to be loving, just, and generous one to another. They do not demand strict equivalent returns for services rendered. Kinship morality is automatically binding.” 38 While other social relationships generally are characterized by reciprocity, kinship is not; kinship is characterized by care, sacrifice and commitment to the welfare of other member of the family and the family group. Thus, marriage and parenthood require the socially-reinforced voluntary subordination or sacrifice of some degree personal autonomy. There are things society cannot allow spouses and parents to do which it might (and in many nations do) allow autonomous adults who have not assumed the responsibilities of marriage or parenting to do. Conversely, there are some things that autonomous adults may choose to do that may at least temporarily disqualify them from assuming the responsibilities of marriage parenthood. In the final analysis, “[t]he natural propensity of kinsmen to sacrifice for each other comes closest to the divine idea, which requires that we sacrifice no less than life itself.” 39 The core attributes of family relations formed by gender-integrating marriage, parenting, and adoption are critically different from other kinds of relationships that are based solely on mere romance and affection without the other integrating familial commitments. Extending family relationship status to partners outside of marriage, kinship and adoption relations also impedes intergenerational injustice. It diverts scarce familial and state resources away from relationship structures that protect children and are child-centered and gives those resources to other members of the older generation in relationships that are adult-centric. 38 39 Id. at __. Id. at __. 15 IV. Statism vs. Familism and the Effort to Redefine Family to Include Same-Sex Partners The legal history of extended families in formal laws and legal systems reflects an ongoing conflict between familism and statism, and changing notions about the relative value of family and state. The trend for at least two centuries has been toward reducing or eliminating the extended family in our lives and replacing or substituting the state. 40 As legal recognition of the roles of the extended family has diminished, legal recognition of the roles, power and responsibility of the state over vulnerable family members has increased. Behind many significant family policy developments of the past century is an ongoing power struggle, often misidentified as between the collective and the individual, or status and contract, but really between state and family as the principal institutions for molding and ordering individuals. What began as a liberating trend, however, has become is many ways an oppressive regime. In its most elementary form, statism today is deemed as an effort by the state to control aspects of personal life and liberty. It can be defined as a form of collectivism in which individuals are forced to be subservient to government, 41 and is often used synonymously with Marxism.42 The trend toward nuclear has contributed to some extent to statism because as extended families are less available to provide assistance when needed to distant family members, and with less willingness to turn to extended family for assistance, it has fallen upon 40 I am indebted to Ruth Deech for this insight made in a conversation in Lyon, France at the World Conference of the International Society of Family Law in July, 2011. 41 Nicolas Provenzo, Rick Santorum’s Moral Outrage: Capitalism Magazine, April 2003, available at http://capitalismmagazine.com/2003/04/rick-santorums-moral-outrage/ ( _).√ 42 Id. 16 the state to provide social, economic, medical and other assistance that in prior times would have been expected to be provided by the extended family. 43 The movement from familism to statism seems to accompany national economic and material development. For example, it has been reported that India’s traditional family organization of one large extended family living under the same roof is quickly breaking down, with a majority of Indian people now living in nuclear families. Recent surveys reflect “a revolution in family life.” 44 Young professionals are away from small towns in search of better life prospects. Better quality of life and the new job market are the primary reasons for this move. Only ten percent (10%) of the nation’s capital now lives in extended family structure, the remaining 90% are living in are nuclear families. 45 A motivating factor for this break down in extended family is the quench independence, especially among wives. In the nuclear family women have the freedom to conform to the demands of their jobs. They do not have to return at a certain time, to make dinner for the big family. 46 This emerging trend away from extended families has far profound impacts. For example, the extended family structure has been the basis for most of India’s business and family law. With the move to nuclear families has come the need to re-write laws that better represent present times. Underlying extended-family-versus-extending-the-family debates over the redefinition of family relations, is a jurisprudential conflict between two competing conceptions of human nature. One views human nature as a means to a materialistic and individualistic end, a 43 See generally Family vs. Statism: Jesusnomic available at http://www.jesusnomics.com/category/statism/ (seen 12 April 2012). Concern for the welfare of children in poor nuclear families has been a powerful influence upon the growth of statism. 44 Dean Nelson, Indian families abandon communal living: The Telegraph: 6 Feb 2011, available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/8306917/Indian-families-abandon-communalliving.html (seen 12 April 2012). 45 Id. 46 Id. 17 transitory view and very small concept. The other views human nature as other-oriented, with individual benefits resulting from higher purposes and commitments. One views relationships primarily as means to self-fulfillment and self-realization and that motivates how the relationships are defined, formed and lived; the other views connection and relationship as forming links in a chain that extends through and for the benefit of many generations. The effort to redefine marriage and parenting reflects the former view, the individualistic view. The effort to protect marriage, parenting and revitalize extended family reflects the latter view. That is the view most likely to strength and build intergenerational solidary and to achieve intergenerational justice. That is why, as Dr, Eberstadt suggests, “proponents of purely material models of development are confronted by the awkward fact that the fertility decline over the past generation has been more rapid in the Arab states than virtually anywhere else on earth [despite poor material development records].” 47 The contrast between recognizing “extended” families and “extending” the legal definition of families to include same-sex unions and same-sex parenting illustrates the statism vs familism dichotomy and the conflict between alienation and affiliation, monopoly and pluralism. It echoes the Bolshevik family law developments of 1917-27 in which radical individualism replaced traditional familism, with devastating results of impoverishment, starvation, and oppression, especially for children. 48 At risk is the continuity of individuals, a generation, and societies – as roots, kinship, identity and bearings are crucial for human welfare, and ultimately meaning, and the glue of communities and societies. One contributes to intergenerational justice; the other thwarts and reduces intergenerational justice and reflects the corrupt “après mois le deluge” philosophy of dying regimes. 47 Eberstadt, supra note __, at __. Lynn D. Wardle, The AWithering Away@ of Marriage: Some Lessons from the Bolshevik Family Law Reforms in Russia, 1917-1926, 2 GEORGETOWN JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY 469 (2004). 48 18 While statism usually begins with good intentions to support and reinforce the family, invariably the state ends up regulating, replacing and supplanting the family. The image is law (state) and order (private ordering, as by families) but the reality is law (state) versus order (families) because they are competing sources of authority. Sociologist Jack Douglas also has observed: “The bureaucracies may begin with fervent expressions of intentions to aid the family, but regardless of good intentions, they must wage war on the family in order to build their own power.” 49 Anthropologist Stanley Diamond notes that: “We live in a law-ridden society; law has cannibalized the institutions which it presumably reinforces or with which it interacts.” 50 Even the movement from status (family relationship, for example) to contract (stateregulated commercial-orientation-dominated relationships) supports the movement from familism to statism. 51 V. Conclusion: Building Intergenerational Solidarity by Recognizing Extended Families The family is the primary expression of and preferred locus for the most meaningful forms of belonging. Like other relationships, inclusion in family relationships requires some 49 Jack Douglas, The Ultimate Costs of the Retreat from Marriage and Family Life, in The Retreat from Marriage 55, 57 (Bryce J. Christensen ed., 1990). See also Alexsandr I. Solzhenitsyn, A World Split Apart, Commencement Address delivered at Harvard University (June 8, 1978). 50 Stanley Diamond, The Rule of Law Versus the Order of Custom, 38 SOC. RES. 42, 44 (1971). See generally Lynn D. Wardle, Children and the Future of Marriage, 17 Regent U. L. Rev. 279, 298 (2004-2005). 51 Henry S. Maine, Ancient Law 109-165 (Ashley Montagu ed., 1986). 19 understanding of the boundaries of those relationships, some exclusion. Some kinds of belonging are wrong even (or especially) in families. The trend towards inclusiveness in public policies is present in family law, as evidenced many examples. Recent controversies about legalizing same-sex marriage, recognizing alternative adult intimate relationships, and alternative forms of parenting are the most recent examples of this trend towards inclusiveness if family law. Applying the standards distinguishing beneficial from detrimental inclusion or exclusion in public policies to these developments, we see that some of the inclusiveness developments in family law have been beneficial and others have been harmful or are potentially harmful. The inclusiveness of a proposed law reform is just one factor in assessing its wisdom; some forms of boundary-erasure or removal are harmful to society, families and individuals. The family is the primary expression of and preferred locus for the most meaningful forms of belonging. Like other relationships, inclusion in family relationships requires some understanding of the boundaries of those relationships, some exclusion. Marriage, kinship and adoption are the natural and time-proven boundaries of family. Some kinds of belonging are wrong even (or especially) in families. The use of same legal labels (like “marriage” or “parent”) to describe in law relationships that have other purposes, sources and dimensions not only causes confusion but it dilutes the value and meaning of the relationship whose label has been co-opted. The trend towards ill-considered inclusiveness in public policies is present in family law, as evidenced many examples. Recent controversies about legalizing same-sex marriage, recognizing alternative adult intimate relationships, and alternative forms of parenting are the most recent examples of this trend towards inclusiveness if family law. Applying the standards distinguishing beneficial from detrimental inclusion or exclusion in public policies to these developments, we see that some of 20 the inclusiveness developments in family law have been beneficial and others have been harmful or are potentially harmful. The inclusiveness of a proposed law reform is just one factor in assessing its wisdom; some forms of boundary-erasure or removal are harmful to society, families and individuals. Redefining marriage and parenting to include same-sex partners raises serious impediments to the natural nuclear and extended family, undermines familism and promotes statism, harms the institution of family, and impedes and diverts resources and focus from intergenerational solidarity and intergenerational justice. For the good of our families and our societies, such deconstruction and reconstructions of the family must be rejected, and the importance of extended family relations should be encouraged. As the Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations (recipient in 2000 of the Theodor-Heuss medal) explains: Our society is living at the expense of its children. The progressing destruction of the environment is evidenced by the depletion of the ozone layer and the greenhouse effect, nuclear waste, extinction of species, desolation of the soil, overfishing, and desforestation of the rain forest. Many of these developments are exacerbated by population growth and a lack of coherent global governance. Moreover, rapidly growing national debts spoil the prospects of future generations. Today's politics violate the basic principle of intergenerational justice because their consequences remove the heritage that will enable future generations to shape their life according to their own wishes and conceptions. 21 They prevent future generations from accessing the same opportunities that we enjoy and depend on today. 52 Today, our legal systems need to facilitate voluntary resort to extended families by recognizing those ties as having legal effect. Attempts to redefine family relations in ways that would dilute the importance of extended family relations of gender-integrating marriage, adoption, and kinship must be rejected. 52 FRFG, Introduction available at http://www.intergenerationaljustice.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=42&Itemid=68 (seen 19 January 2012). 22