Social Conflict in Role-Playing Communities

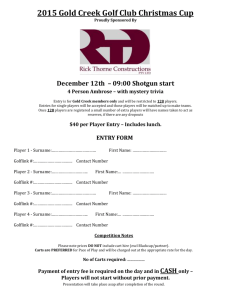

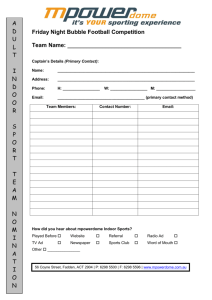

advertisement