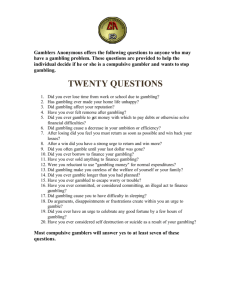

Gender and perceptions of gambling: A pilot project using concept

advertisement