Style in Scientific Writing

advertisement

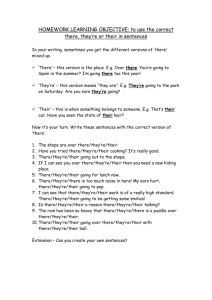

Some Challenges of Scientific Style University Learning Centre Writing Help Ron Cooley, Professor of English ron.cooley@usask.ca http://www.usask.ca/ulc/?q=node/9 Weak Writing =Rejection • “Although there was not a direct relationship between the acceptance rate and the amount of language errors, there was a clear indication that badly written articles correlated with a high rejection rate.” • Coates, Sturgeon, Bohannan, Pasini: ”Language and publication in 'Cardiovascular Research' articles.” Cardiovascular Research 53.2, 2002. Origins of Scientific Style: Thomas Sprat’s History of the Royal Society (1667) • They [the Royal Society] have therefore been most rigorous in putting in execution, the only Remedy, that can be found for this extravagance: and that has been, a constant Resolution, to reject all the amplifications, digressions, and swellings of style: to return back to the primitive purity, and shortness, when men deliver'd so many things, almost in an equal number of words. They have exacted from all their members, a close, naked, natural way of speaking; positive expressions; clear senses; a native easiness: bringing all things as near the Mathematical plainness, as they can: and preferring the language of Artizans, Countrymen, and Merchants, before that, of Wits, or Scholars. What were the early proponents of scientific style against: • Amplification—saying the same thing several times in different words. • Digression—pursuing “side issues” in the main body of a piece of writing. • “swellings”—using more words, or more elaborate words, than necessary. What did the early advocates of scientific style favour? • “Shortness”—choose the fewest words and the simplest words that convey the meaning • “so many things, almost in an equal number of words” • ECONOMY / CONCISENESS • “Mathematical plainness”— they likened language to mathematical calculation. • PRECISION and ACCURACY The Challenge of a Modern Scientific Style? • To say “so many things, almost in an equal number of words” is impossible. • Accuracy and Precision often require us to use more words. • Economy asks us to use fewer words. • How do we balance the two? Is there an order of priority? • Is it better to sacrifice economy to gain accuracy and precision • or to sacrifice accuracy and precision to gain economy? • Why? Use extra words • To increase accuracy and precision • NOT just to “sound scientific” • Compose for accuracy and precision –Include whatever may be necessary • Revise to improve economy and clarity –Cut what you can 2 Main Elements of Style: Diction and Syntax • Diction refers to word choice. Accuracy and precision are largely matters of diction: choosing the correct word or phrase to express your meaning. • Syntax refers to sentence structure. A balanced scientific style uses – simple sentences (often) for clarity and emphasis – compound sentences (occasionally) to add or link information – complex sentences (occasionally) to define relationships between information (e.g. causal, sequential, conditional) Diction • Faults of Accuracy: using a word that doesn’t mean what you intend. Often these are the frequently-confused words. • e.g. effect/affect. • USE A DICTIONARY to check accuracy. Bookmark a good online dictionary so it is always at your fingertips when you write. Some frequently confused words • • • • • • • • • • • • accept adverse affect allot ambiguous among beside can cite compare compare to complement except averse effect a lot ambivalent between besides may site contrast compare with compliment http://www.edufind.com/ENGLISH/writing/easily_confused_words.cfm The Dangers of Electronic Spell Check • Spelling Checkers won’t help you with frequently confused words. • Why not? Diction • Faults of Precision: using a word that is correct/accurate, but not sufficiently precise or specific. • Precision can contribute to economy. • Using precise terms can help you to avoid adding an extra explanatory sentence. Diction • Imprecise: After several days of the new food the animals’ behaviour became abnormal. • More precise: After several days of the new food the animals became lethargic. • More precise: After several days of the new food the animals became agitated. – The imprecise version is perfectly accurate, but it allows for diametrically opposed interpretations. – It would require either an extra sentence of clarification or a more precise term. Diction: Abbreviations • Science writing relies on abbreviations. • It’s easy to use too many abbreviations, or non-standard abbreviations. • Use abbreviations that are customary in your discipline • Normally, spell them out in full the first time. • In the membrane-bound Fo sector of the enzyme, H+ binding and release occur at Asp61 in the middle of the second transmembrane helix (TMH) of subunit c. • Sample sentences from Christine M. Angevine, Kelly A. G. Herold, and Robert H. Fillingame,“Aqueous access pathways in subunit a of rotary ATP synthase extend to both sides of the membrane,” PNAS November 11, 2003 vol. 100 no. 23 13179-13183 Syntax Syntax refers to sentence structure. A balanced scientific style uses – simple sentences (often) for emphasis – compound sentences (occasionally) to add or link information – complex sentences (occasionally) to define relationships between information (e.g. causal, sequential, conditional) Simple Sentences • A simple sentence has a subject (a noun or pronoun); a predicate (a verb), and sometimes an object (another noun or pronoun). • “I like Samosas” • You can add modifiers (descriptive words or phrases) and it’s still a simple sentence. • “In an Indian restaurant I order Samosas as an appetizer” • Don’t be afraid to use simple sentences in scientific writing. It won’t make your writing sound “simplistic.” Simple Sentences • H+ transporting F1Fo ATP synthases consist of two structurally and functionally distinct sectors termed F1 and Fo. • This is still a simple sentence: • H+ transporting F1Fo ATP synthases consist of two structurally and functionally distinct sectors termed F1 and Fo. • Angevine et al. Why use Simple Sentences? • Nouns and verbs in scientific writing are often heavily modified. • A lot of descriptive terms are attached to ensure accuracy and precision. • Adding grammatical complexity on top of complex terminology can make sentences unnecessarily confusing. Long sentences • possibly the single most obvious problem • sentences seemed to try to hide rather than clarify medical data! • ‘The soluble form of B2 micro-globulin (B2 m) HLA class I heavy chain (FHC) consists of three size variants, namely the intact lipid-soluble 43 kDa heavy chain (A variant), released through a shedding process; the truncated water soluble 39 kDa heavy chain (B variant), which lacks the trans-membrane segment and is produced by an alternative RNA splicing and the 34–36 kDa (C variant), which lacks the trans-membrane and intratoplasmatic portion of the molecules.’ • Coates, Sturgeon, Bohannan, Pasini: ”Language and publication in 'Cardiovascular Research' articles.” Cardiovascular Research 53.2, 2002. Angevine et al. use a high proportion of simple sentences. • Very few of the residues reported here are sensitive to inhibition by NEM. This may be due to the restricted size of the pathway through which protons reach cAsp-61. The small size of the Ag+ ion, relative to the bulkier NEM, may make it an ideal probe of the aqueous access pathways in subunit a. • Two simple sentences with a short complex sentence in between. Compound sentences • Compound sentences join simple sentences with coordinating conjunctions • “and,” “but,” “or,” “so,” • “Subunit a is believed to provide access channels to the proton-binding Asp-61 residue, but the actual proton translocation pathway is only partially defined (3–5).” • Angevine et al. Parallel structure • We often make compound sentences more economical by using parallel structure. • Here we have substituted Cys into the second and fifth TMHs of subunit a and [we have-implied] carried out chemical modification with Ag+ and N-ethylmaleimide to define the aqueous accessibility of residues along these helices. • Lists are common instances of parallel structure. Faulty parallel structure • elements in a parallel structure need to be logically and grammatically parallel. • “Arsenic compounds are also used in pigments, wood preservation, insecticides, copper and lead alloys.” • Which term in the list doesn’t fit, and why not? Complex sentences • A complex sentences has an independent clause joined by one or more dependent (or subordinate) clauses • We use complex sentences to express relationships—causation, sequence, contrast • A complex sentence always has a subordinator such as because, since, after, although, when or a relative pronoun such as that, who, or which. Complex sentences • aTMH2 appears to provide an aqueous pathway leading from the periplasm to the center of the membrane, whereas Ag+-sensitive residues in aTMH4 extend from the center of the membrane to the cytoplasmic surface. • When TMH2, -4, and -5 are brought into juxtaposition, they may form an aqueous cavity at the center of the membrane, which would locate primarily to the center of the modeled four-helix bundle. Relative clauses (beginning with “which”/”that”) • Be particularly careful adding relative clauses to the end of a sentence. • These clauses are modifiers, so it MUST be clear which term in the sentence they modify. • When TMH2, -4, and -5 are brought into juxtaposition, they may form an aqueous cavity at the center of the membrane, which would locate primarily to the center of the modeled four-helix bundle (Fig. 6A ). • Which term does the final clause modify? Why it matters whether you use “which” or “that” • Restrictive clauses use “that” • She was taking medications “a” and “b” along with “c” that caused the negative side effects • Non-restrictive clauses use “that” • She was taking medications “a” and “b” along with “c,” which caused the negative side effects Sentence Variety • Too many complex sentences in succession are hard to digest. • Every paragraph needs one or two simple or compound sentences. • Use them for emphasis or clarification, or simply to give your reader a break. Word Order • English sentences rely heavily on word order to convey meaning. Readers expect Subject, Verb and (sometimes Object) to be in close proximity, and usually in that order. • So write most sentences in a way that satisfies your reader’s expectations. • Avoid putting too many descriptive phrases and clauses between the subject and verb! Word Order • H+ transporting F1Fo ATP synthases consist of two structurally and functionally distinct sectors termed F1 and Fo. • This sentence is clear partly because the grammatically essential elements (subject and verb) are close together, in customary order. A difficult scientific sentence: • The osmoregulatory organ, which is located at the base of the third dorsal spine on the outer margin of the terminal papillae and functions by expelling excess sodium ions, activates only under hypertonic conditions. • • Writing in the Sciences http://www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/sciences.html A difficult scientific sentence: • The osmoregulatory organ, which is located at the base of the third dorsal spine on the outer margin of the terminal papillae and functions by expelling excess sodium ions, activates only under hypertonic conditions. • The Subject and Verb are far apart Revised for economy • The osmoregulatory organ, located at the base of the third dorsal spine on the outer margin of the terminal papillae, expels excess sodium ions, but only under hypertonic conditions. – “”which” clause turned into a descriptive phrase – Participle (“expelling”) turned back into main verb – Excess verbs (“functions” and “activates”) eliminated Further revised for clarity and variety • Located at the base of the third dorsal spine on the outer margin of the terminal papillae, the osmoregulatory organ expels excess sodium ions, but only under hypertonic conditions. – Descriptive phrase shifted to introductory position – Subject verb and object close together • We tend to begin sentences with the subject. • It’s more important for the subject and verb to be close together than for the subject to be the first word. Verb tense • The general stylistic rule is to use present tense for statements of fact, definitions, generalizations, abstract or theoretical statements, • and use past tense for description of real world events. • In science writing this means different parts of a paper are predominantly in different tenses. • Be consistent within sections. Past Tense • Past tense is normally used to describe experimental procedures and observations. • All mutations were confirmed by sequencing the cloned fragment through the ligation sites. All experiments were performed with the mutant whole operon plasmid derivative of pCMA113 in the unc operon deletion host strain JWP292 (2). All plasmid transformant strains were tested for growth on succinate and glucose as described (5). Present Tense • Present Tense tends to be used in stating research questions, reviewing literature, and generalizing from observations. • The role of subunit a in promoting proton translocation and rotary motion in the Escherichia coli F1Fo ATP synthase is poorly understood. (Opening sentence) • The most Ag+-sensitive residues in aTMH5 cluster at the center of the membrane and extend toward the periplasmic surface. (Discussion Section) Active and Passive voice in Scientific Writing What IS the “passive voice”? • The passive voice makes the object of the action into the subject of the sentence. • Passive: The experiment was conducted (by . . . ) • Active: We conducted the experiment. Why Science writing relies on the passive voice • the passive voice is especially helpful (and even regarded as mandatory) in scientific or technical writing or lab reports, where the actor is not really important but the process or principle being described is of ultimate importance. Instead of writing "I poured 20 cc of acid into the beaker," we would write "Twenty cc of acid is/was poured into the beaker." The passive voice is also useful when describing, say, a mechanical process in which the details of process are much more important than anyone's taking responsibility for the action: "The first coat of primer paint is applied immediately after the acid rinse." • Marc E. Tischler, SCIENTIFIC WRITING BOOKLET, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biophysics University of Arizona Problems with Passive constructions • Passive constructions are a source of wordiness, and sometimes obscurity. • Often agency is important in science (e.g. when claiming credit for accomplishments) • We have previously proposed a model for rotary function in which the concerted swiveling of helices within the four-helix bundle of subunit a may provide a mechanism of gating alternate access of protons to cAsp-61, and in turn be linked to the mechanical movements driving cring rotation (4). (Angevine et al) • The basic style rule is to use the active voice when you can, the passive voice when you have good reason. Active Voice works well when the experimenter is not the subject of the sentence. • The c subunit spans the membrane as a hairpin of two α-helices, and in the case of E. coli, contains the essential Asp-61 residue at the center of the second transmembrane helix (TMH). • You could rewrite this sentence in the passive voice (The membrane is spanned by the c subunit . . . ) but it would become very confusing. Angevine et al. use passive voice to describe experimental procedures • All mutations were confirmed by sequencing the cloned fragment through the ligation sites. All experiments were performed with the mutant whole operon plasmid derivative of pCMA113 in the unc operon deletion host strain JWP292 (2). All plasmid transformant strains were tested for growth on succinate and glucose as described (5). • Thanks for your Patience! Workshopping Sentences • The results of the investigations conducted in this thesis show that the achieved control designs are effective in damping interarea oscillations as well as the high torsional torques induced in turbinegenerator shafts due to clearing and highspeed reclosing of transmission system faults. • Amr Eldamaty, “Damping Interarea and Torsional Oscillations Using FACTS Devices.” Revised for clarity and economy • These investigations show that the achieved control designs are effective in damping interarea oscillations as well as the high torsional torques induced in turbine-generator shafts by clearing and high-speed reclosing of transmission system faults. Workshopping Sentences • In this study, success has also been achieved in the integration of the slow (kinetically controlled) formation of TMs and copper-tetrathiomolybdate (TM4) complexation into the previously developed model for the rapidly equilibrating copper-ligand speciation. • Joseph Essilfie-Dughan, “Speciation Modelling of Copper(II) in the Thiomolybdate – Contaminated Bovine Rumen.” • This work (or method or technique) also successfully integrated the slow (kinetically controlled) formation of TMs and copper-tetrathiomolybdate (TM4) complexation into the previously developed model for the rapidly equilibrating copper-ligand speciation. Workshopping Sentences • The structure revealed that no significant structural rearrangements are induced by the mutation and the inability to accept phosphotransfer from Enzyme I is due to electrostatic disruption of the interaction of these proteins. • Scott Napper, “Phosphorylation Sites of HPr” Other tips for Economy (avoiding wordiness) • • • • • • • • • • 1. Eliminate unnecessary determiners and modifiers 2. Change phrases into single words 3. Change unnecessary that, who, and which clauses into phrases 4. Avoid overusing expletives at the beginning of sentences 5. Use active rather than passive verbs (See separate discussion) 6. Avoid overusing noun forms of verbs 7. Reword unnecessary infinitive phrases 8. Replace circumlocutions with direct expressions 9. Omit words that explain the obvious or provide excessive detail 10. Omit repetitive wording