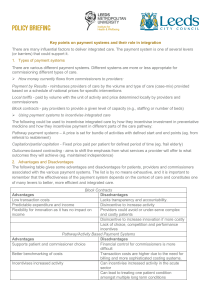

The Potential of Global Payment

advertisement